Abstract

Parenteral nutrition (PN) therapy provides essential nutrients intravenously to patients unable to receive enteral nutrition due to various clinical conditions. This review aims to summarize the current evidence and guidelines for PN therapy. Key aspects covered include-Indications and contraindications, Nutrient composition and formulation, Vascular access and complications management, Metabolic and electrolyte monitoring, Pediatric and geriatric considerations, Transition to oral/enteral nutrition. Recent advances in PN therapy, such as standardized protocols and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, are highlighted. Challenges and future directions, including personalized nutrition and reducing complications, are discussed.This review serves as a valuable resource for healthcare professionals to optimize PN therapy, improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Keywords

parenteral Nutrition, Monitoring, enteral Nutrition, PN therapy, parenteral Nutrition associated complications.

Introduction

The crucial portion of parenteral nutrition (PN) that deals with the patient directly is the administration phase. The patient may experience risks during this period if mistakes or failures in adhering to recommended best practices occur.[1-3] In critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), appropriate nutrition management tries to prevent malnutrition in patients who are primarily well-nourished and to stop the progression of preexisting malnutrition. The provision of optimal nutrition therapy can help preserve organ function, modulate the inflammatory response to surgery, trauma, or severe disease, and optimize metabolic status. These three benefits may ultimately lead to improved clinical patient outcomes. [4, 5]

Malnutrition affects many patients as a result of anorexia, intestinal (GI) surgery, absorption problems, and GI side effects from medication .Even in patients who are currently in good nutritional health, long-term medication may cause sadness, sluggishness, and a low quality of life, which may worsen nutritional status and vice versa [6]. Enhancing the patient's nutritional state improves clinical outcomes, including a decrease in the death rate and a reduction in hospital stays [7].

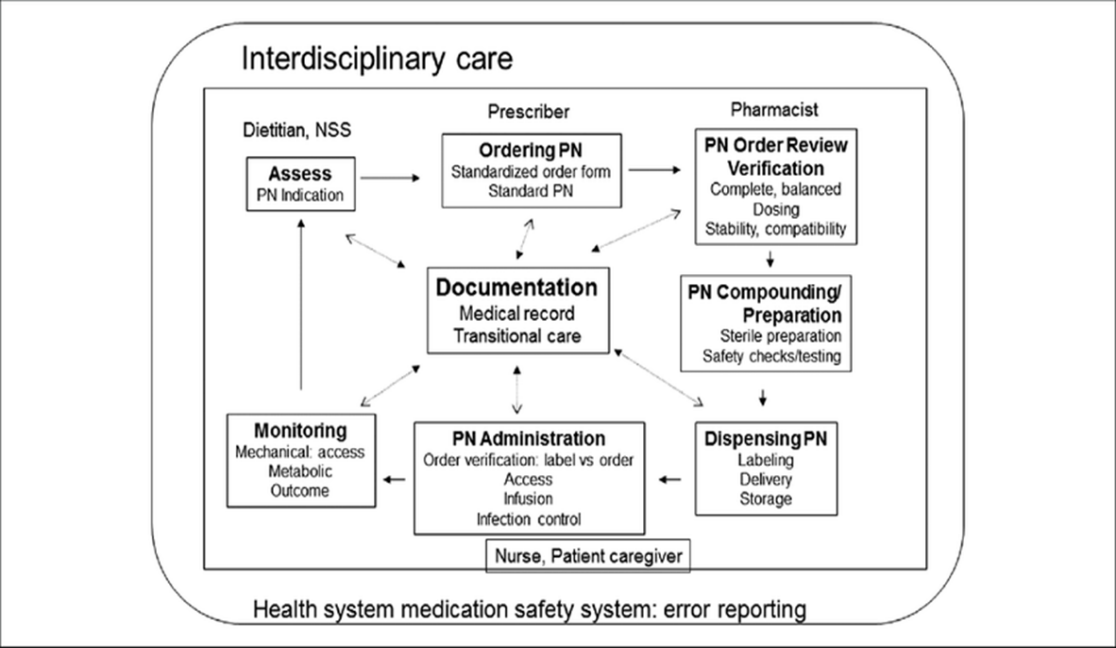

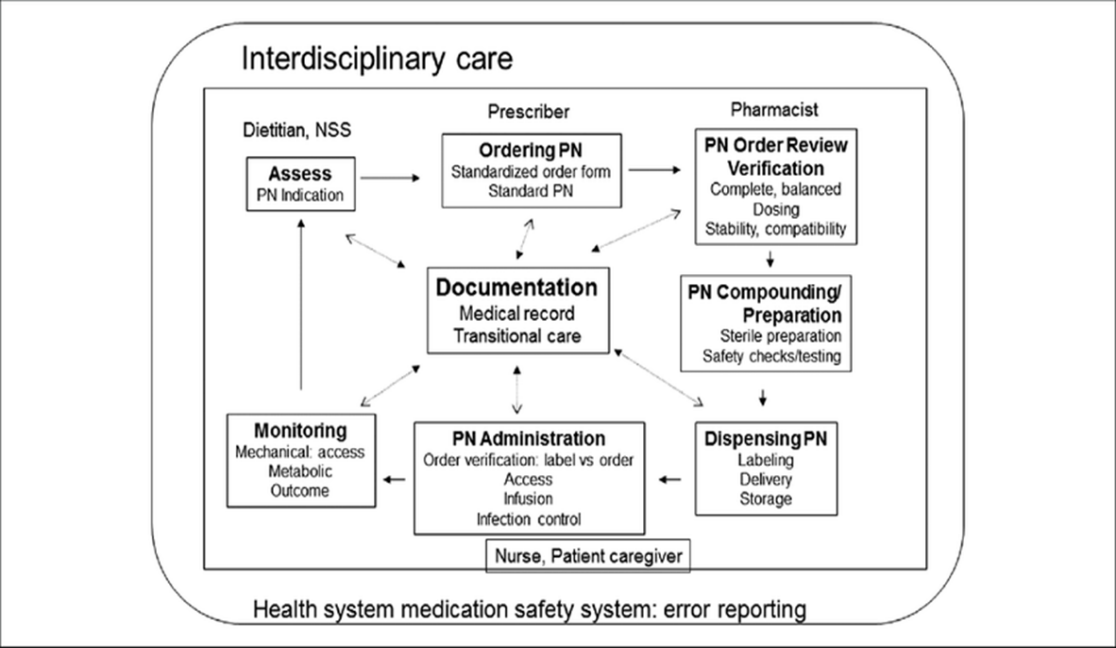

Even restricting evaluations to the US and Europe, the global proportion of hospitalized patients suffering from malnutrition surpasses 30%, despite the constant reporting of the significance of nutrition therapy [8]. The process of using PNs (as shown in Figure 1) comprises several essential processes, such as patient assessment, order review, preparation and administration, prescribing and ordering, routine patient monitoring, and patient reanalysis.[9]

Figure 1. The parenteral nutrition (PN) utilization process:

Defination:

Parenteral nutrition, or PN, is the intravenous administration of a synthetic, nutritionally balanced mixture of sterile nutrients. This can be given as complete parenteral nutrition, which is limited oral or enteral feeding, or as the only source of nutrition [10].

Indications:

Nutrition administered intravenously outside of the gastrointestinal tract is known as parenteral nutrition. When an IV is the patient's only source of sustenance, this is known as total parenteral nutrition (TPN). When gastrointestinal function is compromised and enteral nourishment is contraindicated, whole parenteral nutrition is recommended. Because enteral meal consumption is less expensive and linked to fewer consequences including blood clots and infections, it is recommended over parenteral intake; nevertheless, it does require a functioning gastrointestinal tract. [11,12] Because it is safer and more physiological, the oral/enteral route should always be the preferred mode of providing nutritional assistance for patients; nevertheless, there are several situations in which this may not be feasible or suitable.[13] In patients with a functional and accessible gastrointestinal system, EN is preferred over PN when nutritional support is needed. PN is indicated when enteral or oral feeding is either impossible or insufficient. [14] In adult subjects, intestinal failure (IF), which is defined as a reduction in gut functions below the bare minimum required for the absorption of nutrients from the gastrointestinal tract to maintain health and growth, is primarily indicated by high-output fistulas, severe intestinal obstruction, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, radiation enteritis, or intestinal failure brought on by illness or treatment (short bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel diseases, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, etc.) [14,15].

Chowdary and Reddy (2010) state that TPN has a number of indications. These include:

- GI fistulas with high flow.

- bowel pseudo-obstruction with food intolerance.

- chronic intestinal obstruction as in intestinal cancer.

- post-operative bowel anastomosis leak.

- immature or congenital gastrointestinal malformations in infants.

- small bowel obstruction.

- hypercatabolic states due to sepsis, polytrauma, and major fractures.

- an expected period of nothing by mouth (NPO) status longer than seven days, as in patients with inflammatory bowel disease exacerbations and critically ill patients [11,16].

- When the baby's gut is too immature or has congenital malformations.

- when the patient has chronic diarrhea and vomiting.

- when the patient is severely malnourished and requires surgery, chemotherapy, and so forth.

- when the patient's gastrointestinal tract is paralyzed and nonfunctional, as in the case of small bowel obstruction.

- when greater than seven days of nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status is expected, as in the case of inflammatory bowel disease, patients experiencing an acute exacerbation, critically ill patients, and so on [17,18].

Composition of PN:

To prevent nutrient deficits, a mixed nutritional solution consisting of carbs, protein, and lipids is advised once PN is indicated. Fluids, micronutrients (electrolytes, vitamins, and trace elements), and macronutrients (amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipid emulsions) are examples of PN components. [14,19]. TPN composition should be modified by clinicians to meet the needs of each patient. Proteins, dextrose, and lipid emulsions are the three primary macronutrients [11,20]. A two-in-one system that contains glucose and amino acids or an all-in-one system that contains fat, carbs, and amino acids are two more systems that can be used to administer PN. Along with micronutrients, the two-in-one method contains glucose and amino acids in a single bag; however, the fatty product must be administered separately. All of the nutrients are combined in a single bag and infused at the same time in an all-in-one system, also known as total PN (TPN) or total parenteral admixture (TNA). Full PN is sometimes known as TPN to distinguish it from supplemental PN because PN can be administered as a supplement when oral nutrition or EN is insufficient [14].

1.proteins :

Intravenous, sterile, free amino acid solutions that also offer energy (4 kal/g) are used to meet the protein needs of patients undergoing PN [14,21]. Amino acids are utilized as a source of nitrogen for protein synthesis and to replenish protein stores that have been exhausted due to illness. Although the amount of nitrogen in amino acid solutions varies according to the concentration of the amino acids, it is commonly considered that the nitrogen content is 16% (6.25 g of protein = 1 g of nitrogen) [14,22].A mixture of essential and non-essential amino acids, excluding glutamine and arginine Adults should consume between 0.8 and 1 mg of protein per kilogram per day. The patient’s condition determines this modification. Patients with acute hepatic encephalopathy require temporary protein restriction to 0.8 gm/kg/day, patients on hemodialysis require 1.2 to 1.3 gm/kg/day, critically ill patients require 1.5 gm/kg/day, and patients with chronic renal failure are given 0.6 to 0.8 gm/kg/day.[11,20].The World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines for appropriate necessary amino acid proportions serve as the foundation for the amino acid profile.[23].

2.Carbohydrates:

Dextrose is the most widely utilized carbohydrate substrate; when hydrated, it yields 3.4 kcal/g of carbohydrate and is primarily used in the USA and Canada. In contrast, 4 kcal/g of carbohydrates are provided by a non-hydrated type of dextrose that is primarily utilized in Europe. [24]. The maximal rate of glucose utilization is 5–7 mg/kg/min. Hyperglycaemia and hypertriglyceridemia can be caused by taking too much carbohydrates as supplements[11].The most used form of parenteral carbohydrate administration is dextrose monohydrate, which comes in concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 70%. There are 3.4 calories in one gram of dextrose. The PPN uses ? 10?xtrose solutions for safe osmolarity infusion, whereas the majority of TPN regimens use ? 25?xtrose. Although fructose, sorbitol, xylitol, and glycerol have all been and are being investigated as sources of carbohydrates for parenteral nourishment, none of them have been found to offer a clear benefit over dextrose, and the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has not approved their use[25].

3.Lipids:

Because they provide necessary fatty acids and reduce reliance on glucose as a primary source of non-protein energy, lipid emulsions are a crucial part of PN. The concentration of commercially available IVFEs for PN is 20%. The glycerol in IVFE adds calories so that each gram of fat in 20% IVFE is equal to 10 kcal, even though each gram of fat delivers 9 kcal . Typically, 20–30% of daily calories come from lipids; excessive lipid intake may cause hypertriglyceridemia and fat overload syndrome. To prevent lipid overload, IVFE dosages should generally not exceed 1 g/kg body weight per day [14].

4.Micronutrients Requirements:

Micronutrients include vitamins, trace minerals, and electrolytes. It is advised that each liter of parenteral infusion solution have 100–150 mEq of sodium, 50–100 mEq of potassium, 8–24 mEq of magnesium, 10–20 mEq of calcium, and 15–30 mEq of phosphorous. To avoid precipitation, a calcium and phosphorous total of less than 40 mEq is advised. Because of their better solubility and compatibility, calcium and magnesium are typically supplied as gluconate and sulphate, respectively. Considerations for changing these standard electrolyte recommendations should include renal failure, cardiac issues, intestinal losses, the patient’s level of hydration, and clinical judgment.[26].

Administration:

Most hospitalized patients using PN are short-term users, and they usually get PN as a continuous infusion for 24 hours. Administration spread out over a 24-hour period allows for less manipulation and a reduced infusion rate, which reduces the risk of fluid and glucose overload. Nonetheless, home PN is frequently given according to a cyclic (discontinuous) regimen. A portion of the day or night's cyclic administration gives the patient independence from the intravenous tubing and pump device [27]. A central venous catheter is used to administer whole parenteral nourishment. An access device called a central venous catheter is used to deliver chemotherapy, nourishment, and other treatments. It ends in either the right atrium or the superior vena cava. A central venous catheter, implanted port, or peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) could be used to establish this access. A PICC line can be inserted by clinicians into the median cubital vein, basilic vein, cephalic vein, or brachial vein. Because of its superficial placement and bigger size, the basilic vein is the preferred vein. The catheter travels from the basilic vein into the axillary, subclavian, and superior vena cava veins. PICC lines may be necessary if TPN is given for a few weeks or months. The femoral, subclavian, or internal jugular are the three main central veins through which central venous catheters can be inserted. TPN is given for several months to years using central venous catheters. A device that is placed beneath the skin of the chest and has a catheter connected that is placed into the superior vena cava is known as an implanted port. For years, TPN has been administered via implanted ports.[18] Total parenteral nutrition is not delivered by a peripheral intravenous catheter (Peripheral Parenteral Nutrition, PPN) because of its high osmolarity.The PPN must have an osmolarity of less than 900 mOsm. Larger volume feedings are required because to the reduced concentration, and a high fat content is required. Since high osmolarity irritates peripheral veins, central venous access is used to administer TPN.[11,28].

Complications:

For PN, hyperglycemia continues to be the most frequent consequence. Even in patients who are not critically ill, a high prevalence of hyperglycemia during PN therapy has been documented . It has been demonstrated that in critically sick patients, strict glycemic control of less than 110 mg/dL lowers mortality and morbidity . Subsequent research, however, also demonstrated that strict glucose control raised the risk of hypoglycemia episodes and mortality and that glycemic control near 180 mg/dL produced better results than lower objectives [14,29].

Liver disease and hypertriglyceridemia have been linked to lipid excess. While lipids from non-nutritive sources like propofol are included in the standard dose of IVFE, which is less than 1.5 kg/kg/day, patients at risk of hypertriglyceridemia are advised to receive up to 1 g/kg/day. One common metabolic consequence linked to fat delivery in PN is hypertriglyceridemia. [14,30].

- Catheter-Related Complications:

Problems Associated with Catheters One of the most significant side effects of PN is CRBSI. Central line infections may result in sepsis, shock, and even death. When inserting and maintaining any central VAD, CRBSIs should be taken into account as a risk factor because they can raise costs, length of stay, morbidity, and death [31].

Adverse Effect:

Infection, hyperglycemia, hepatic steatosis, essential fatty acid shortage, electrolyte abnormalities, acid-base disturbances, hypertriglyceridemia, bacterial translocation, and gut integrity damage are some of the short-term potential side effects of PN. Dermatitis, baldness, poor wound healing, increased platelet aggregation, increased capillary fragility, and hepatic dysfunction are all signs of an essential fatty acid deficit.[32] Long-term negative effects include all of the short-term issues listed above, as well as vitamin and mineral deficiencies and toxicity, aluminum toxicity in patients and newborns, and renal impairment.[17].

CONCLUSION:

Significant improvements in PN formulations and procedures over the past few decades have improved our knowledge of what is safe and decreased PN problems. PN is a specialized therapy approach that can assist in improving hospitalized patients' nutritional status. When PN is used appropriately, nutritional indicators are improved and the risk of malnutrition-related problems is decreased. On the other hand, improperly started PN is linked to higher expenses and needless patient risk. As a result, programs that evaluate and employ techniques and protocols to lower PN-related problems and enhance therapeutic results ought to be given top priority.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The authors would like express to thankful to our Teacher Dr. Salve mam and prof. Ajit B. Tuwar for their Guidance and support for this review article. Special thanks to Sangale sir for guidance.

REFERENCES

- Patricia Worthington, Michael D. Kraft,Reid Nishikawa, Peggi Guenter, Gordon S. Sacks, and the ASPEN PN Safety Committee1. Update on the Use of Filters for Parenteral Nutrition: An ASPEN Position Paper. Nutrition in Clinical Practice Volume 36 Number 1( February 2021) 29–39 DOI: 10.1002/ncp.10587

- Ayers P, Adams S, Boullata J, et al. American Society for Parenteraland Enteral Nutrition. A.S.P.E.N. Parenteral nutrition safety consensus recommendations. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:296-333.

- Boullata JI, Gilbert K, Sacks GS, et al. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines:parenteral nutrition ordering, order review, compounding, labeling,and dispensing. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(3):334-377.

- Mary S. McCarthy, Factors associated with the need of parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients after the initiation of enteral nutrition therapy (2023) ,Front. Nutr. 10:1250305 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1250305

- Lambell KJ, Tatucu-Babet OA, Chapple LA, Gantner D, Ridley EJ. Nutrition therapy in critical illness: a review of the literature for clinicians. Crit Care. (2020) 24:35. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2739-4

- Cheon, S.; Oh, S.-H.; Kim,J.-T.; Choi, H.-G.; Park, H.; Chung,J.-E. Nutrition Therapy by NutritionSupport Team: A Comparison ofMulti-Chamber Bag and CustomizedParenteral Nutrition in Hospitalized Patients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2531.

- Agarwal, E.; Ferguson, M.; Banks, M.; Batterham, M.; Bauer, J.; Capra, S.; Isenring, E. Malnutrition and poor food intake are associated with prolonged hospital stay, frequent readmissions, and greater in-hospital mortality: Results from the Nutrition Care Day Survey 2010. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 737–745. [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Pichard, C.; Lochs, H.; Pirlich, M. Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 5–15.[CrossRef]

- Paul E. Wischmeyer,Stanislaw Klek,Mette M. Berger,David Berlana,Brenda Gray, Joe Ybarra,Phil Ayers, Parenteral nutrition in clinical practice: International Challenges and strategies (2024).

- Nashiz Inayet, Penny J Neild. Parenteral nutrition DOI: no10.4997/JRCPE.2015.111 · Source: PubMed [ResearchGate]

- Marah Hamdan; Yana Puckett Total parenteral Nutrition. [StatPearls]

- Braunschweig C, Liang H, Sheean P. Indications for administration of parenteral nutrition in adults. Nutr Clin Pract. 2004 Jun;19(3):255-62. [PubMed]

- Campbell SE, Avenell A, Walker AE. Assessment of nutritional Status in hospital in-patients. QJM 2002; 95: 83–7

- Berlana, D. Parenteral Nutrition Overview. Nutrients 2022, [MDPI]

- Mueller, C.M. (Ed. ) Mueller, C.M. (Ed.) The ASPEN Nutrition Support Core Curriculum, 3rd ed.; American Society of Parenteral And Enteral Nutrition: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-188-962-231-6.

- Maudar KK. TOTAL PARENTERAL NUTRITION. Med J Armed Forces India. 1995 Apr;51(2):122-126. [PMC Free Article] [Pubmed]

- Koneru Veera Raghava Chowdary and Pothula Narasimha Reddy Parenteral nutrition: Revisited Indian J Anaesth. 2010 Mar-Apr; 54(2): 95–103.[PubMed]

- Mirtallo F. Introduction to parenteral nutrition. In: Gottschlich M, editor. The Science and Practice of Nutrition Support. Kendal Hunt Publishing; 2001. Pp. 211–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, J.E.; Berlana, D.; Ukleja, A.; Boullata, J. Clinical, Ergonomic, and Economic Outcomes With Multichamber Bags Compared With (Hospital) Pharmacy Compounded Bags and Multibottle Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 1162–1177.

- Chowdary KV, Reddy PN. Parenteral nutrition: Revisited. Indian J Anaesth. 2010 Mar;54(2):95-103. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mueller, C.M. (Ed. ) Mueller, C.M. (Ed.) The ASPEN Nutrition Support Core Curriculum, 3rd ed.; American Society of Parenteral And Enteral Nutrition: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-188-962-231-6

- Iacone, R.; Scanzano, C.; Santarpia, L.; Cioffi, I.; Contaldo, F.; Pasanisi, F. Macronutrients in Parenteral Nutrition: Amino Acids.Nutrients 2020, 12, 772.

- Technical Report Series 724. Geneva: WHO; 1985. WHO (World Health Organisation): Energy and protein requirements: Report of a joint FAO/WHO/UNU expert consultation. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirtallo, J.; Canada, T.; Johnson, D.; Kumpf, V.; Petersen, C.; Sacks, G.; Seres, D.; Guenter, P. Safe Practices for Parenteral Nutrition. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2004, 28, S39–S70.

- Karlstad MD, DeMichele SJ, Bistrian BR, Blackburn GL. Effect of total parenteral nutrition with xylitol on protein and energy metabolism in thermally injured rats. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1991;15:445–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry RS, Jurgens RW, Jr, Sturgeon R, Athanikar N, Welco A, Van Leuven M. Compatibility of calcium chloride and calcium gluconate with sodium phosphate in a mixed TPN solution. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1980;37:673–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuerda, C.; Pironi, L.; Arends, J.; Bozzetti, F.; Gillanders, L.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Joly, F.; Kelly, D.; Lal, S.; Staun, M.; et al. ESPENPractical Guideline: Clinical Nutrition in Chronic Intestinal Failure.Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5196–5220

- Gonzalez R, Cassaro S. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Sep 4, 2023. Percutaneous Central Catheter. [PubMed]

- Elizabeth, P.-C.; Rogelio Ramón, P.-R.; Félix Alberto, M.-M.Hyperglycemia Associated with Parenteral Nutrition in NoncriticalPatients. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 22, 20011

- Visschers, R.G.J.; Olde Damink, S.W.M.; Gehlen, J.M.L.G.; Winkens, B.; Soeters, P.B.; van Gemert, W.G. Treatment of Hypertriglyceridemia in Patients Receiving Parenteral Nutrition. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2011, 35, 610–615.

- Parienti, J.-J.; Mongardon, N.; Mégarbane, B.; Mira, J.-P.; Kalfon, P.; Gros, A.; Marqué, S.; Thuong, M.; Pottier, V.; Ramakers, M.;Et al. Intravascular Complications of Central Venous Catheterization by Insertion

- Stegink LD, Freeman JB, Wispe J, Connor WE. Absence of the biochemical symptoms of essential fatty acid deficiency in surgical patients undergoing protein sparing therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:388–93. Doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nishigandha Sandip Kharde* 1

Nishigandha Sandip Kharde* 1

Ajit B. Tuwar 2

Ajit B. Tuwar 2

Megha Salve 3

Megha Salve 3

10.5281/zenodo.14040050

10.5281/zenodo.14040050