Abstract

Food waste accumulation and resource depletion pose serious environmental and socioeconomic issues. Using food waste byproducts as components for cosmetic products is one approach that shows promise. The purpose of this study is to suggest olive leaf extracts and clementine peels as value-added bio-products for a cosmetic cream. Super critical extraction was used to produce extracts with an antioxidant activity of about 25%. Up to a concentration of 4% v/v ratio, the extracts had no cytotoxic effects on keratinocyte cells after 24 hours. Turbiscan studies at room temperature and at an extreme 40 °C showed that the creams’ stability was not affected by the addition of clementine peels and olive leaf extracts.

Keywords

Waste to Potential, accumulation and resource, cosmetic products.

Introduction

Acording to estimates, the European Union produced about 58 million kg of food waste in 2023 On human volunteers, the final cosmetic compositions’ safety characteristics were further shown in vivo. We examined changes in the skin’s erythematous index and trans-epidermal water loss, and the results indicated profiles that nearly coincided with the negative control. Furthermore, rheological examination of the resultant creams demonstrates their appropriate spreadability with comparable pseudoplastic profiles; however, a minor decrease in viscosity was noted by increasing the concentrations of the extracts. The suggested method emphasizes the benefit of combining supercritical fluid extraction with byproduct resources to create a face cream that is both safe and environmentally beneficial.,[1]

- 131 kg of food waste per person year. Hence posing a serious environmental and socioeconomic issue [2]. The development of new approaches to obtaining biomaterials from food waste is an urgent priority, and several strategies have been put in place to develop a circular economy able to reduce environmental degradation and resource depletion [3,4,5]. In this regard, the beauty industry’s utilization of chemicals produced from byproducts offers a possible substitute for traditional methods [6,7]. This study assesses the use of olive leaf extract and clementine peels in accordance with this methodology.Vegetables and fruits are a vital component of our diet, and their proven nutritional worth has been thoroughly investigated for many years. [8]The plants produce a broad range of “secondary” metabolites in addition to “primary” metabolites (such as saccharides, lipids, and amino acids), which are essential for plant defense against [9]

The use of chemicals made from byproducts by the beauty industry presents a potential replacement for conventional methods. The current study evaluates the cosmetic application of olive leaf extract and clemtine peels using this technology. Highlighting their roles as ingredients in the creation of face creams Due to their numerous health advantages, olive leaf extract and clementin peels are excellent raw materials for the cosmetics industry.

1)skin care preparation

a) cream properties ---

1) vitamins -Within a few hours, dietary ascorbate is absorbed and dispersed throughout the body. The biochemical importance of vitamin C in cosmetic is primarily based on its reducing potential, as it is required in number of hydroxylation reactions. Ascorbate is needed as a reductant by several hydroxylases that are involved in the synthesis of collagen . It appears that the epidermis of human skin, which is reliant on dietary vitamin C, has levels that are roughly five times higher than those of the dermis [12].

b). Anti-aging -preventing aging Natural Antiaging skin care primarily focuses slow or reversal methods to the indications of aging. The ingredients used for this purpose come from natural extractives that have been used for a very long time. Skin shape changes are invariably signs of age, whether they are brought on by internal oxidative stress or external aging. The skin must contend with endogenous creation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other free radicals, which are continuously created during physiological cellular metabolism, in addition to exogenous inducers of oxidative attack. In order to counteract ROS’s detrimental effects,

C) skin lightening active –Skin color is determined by the ratio and presence of several chromophores, such as bilirubin (yellow), decreased haemoglobin (bluish red), and oxyhaemoglobin (bright red), which are located in the dermal tiny blood vessels (13).

2). USES Of cream

The provision of a barrier to protect the skin. …

To aid in the retention of moisture (especially water-in-oil creams)

Cleansing

Emollient effects.

As a vehicle for drug substances such as local anaesthetics, anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs or corticosteroids), hormones, antibiotics, antifungals or counter-irritants.

Olive Leach

- Chemical constituents –oleuropein (24.54 %), followed by hydroxytyrosol (1.46 %), luteolin-7- Oglucoside (1.38 %), verbascoside (1.11 %), apigenin-7-O-glucoside (1.37 %) and tyrosol (0.71 %)

- Biological source –The biological source of olive leaves is the olive tree, Olea europaea. Olive leaves are a byproduct of olive tree cultivation and are available year-round. They are collected during pruning, harvest, and processing.

- Family –The olive leaf belongs to the Oleaceae

- MATERIALS AND METHOD

a)Material

One kilogram of olive tree (Olea europaea) leaves, belonging to the “Megaritiki” cultivar, were gathered from pesticide-free olive trees in the “Afidnes” region and dried for nine days at room temperature in the dark. 670.4 g of dried leaf material were collected. The PLA was produced by solid state hydrolysis of a commercial resin (PLI005, NaturePlast, Ifs, France) at 60 °C in an acidic environment (pH 3) with a viscosity-average molecular weight of 46,000 g/mol [14]. The emulsion stabilizer, Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA), had an average molecular weight of 88,000–97,000 and was 87–89% hydrolyzed. Analytical grade organic solvents were all that were utilized.[15]

b) method

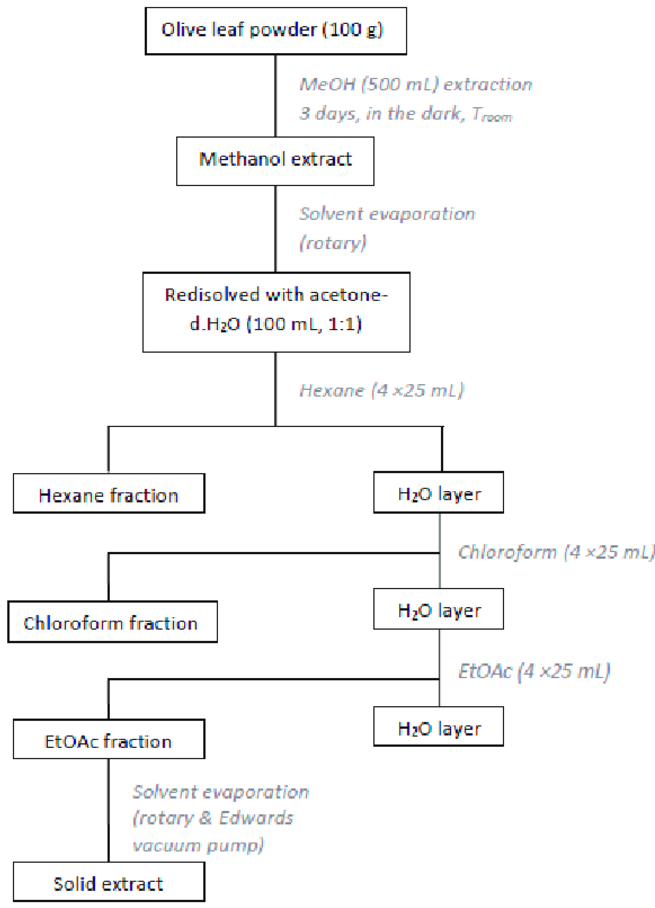

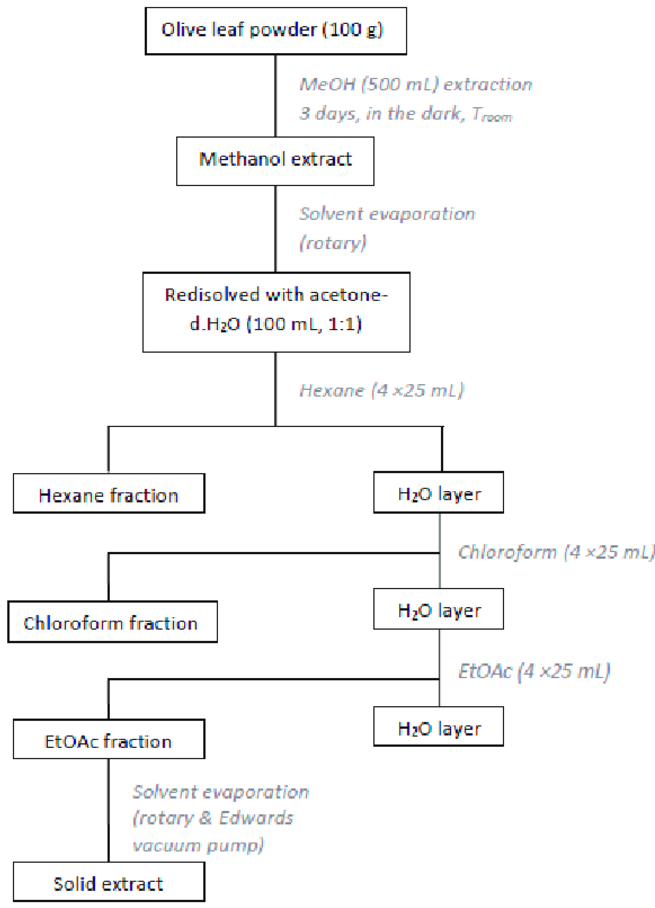

Preparation of Olive Leaves Extract (OLE)

Using organic solvents with varying polarities, the dried olive leaves were extracted [15]. In summary, 500 mL of methanol was extracted from 100 g of dried leaves for three days at room temperature and in the dark. The methanol extract was then concentrated and filtered while operating at a lower pressure. The residue was again dissolved in a 100 mL, 1:1 acetone-water solution, and then cleaned with 4 × 25 mL of hexane, 4 × 25 mL of chloroform, and 4 × 25 mL of ethyl acetate. After being mixed, the ethyl acetate extracts were concentrated in a vacuum (Figure 1). The 2.2 g solid residue was gathered and stored in glass vials with dark colors at 4 °C. For the remaining dry material, the process was repeated. Lastly, a total amount of 670.4 g of dried olive leaves

Citrus peels

Chemical constituents ---monoterpene (limonene), sesquiterpene hydrocarbons and their oxygenated derivatives including: aldehydes (citral), ketones, acids, alcohols (linalool) and esters

Biological source –fresh or dried outer part of the pericarp of Citrus aurantium Linn

Family –Rutaceae

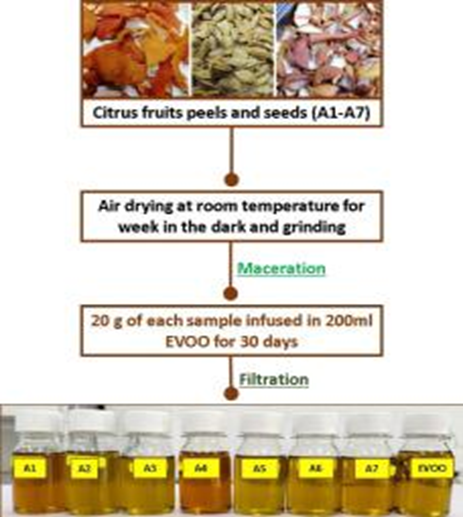

Olive oil and citrus peels

Peels from clementines and extracts from olive leaves have several health benefits, which makes them good raw materials for the cosmetics sector Polyphenols, which act as the primary bioactive molecules for plants protecting themselves against pathogens and stress situations, make up the majority of the bioactive components in the extracts of these byproducts [16]. There are many benefits for skincare when polyphenols from olive leaf and clementine peel extracts are used to cosmetics. Renowned for their strong antioxidant capabilities, these substances efficiently scavenge free radicals that may otherwise result in premature aging and skin damage Furthermore, they are useful substances to treat irritated skin because of their anti-inflammatory qualities, which lessen redness and encourage a more even complexion [,17, 18]. Additionally, polyphenols have amazing skin-brightening properties that assist to lessen the appearance of the skin

The water used In the extraction of fiber from citrus or other fruits, in washing procedures, or in other steps of the food production chain is another intriguing—yet little-studied—method of reusing waste. Numerous substances found in this water waste have the potential to be advantageous from a technological and health standpoint. They can also be utilized as an enhancement for a cosmetic formulation, giving it a pleasing scent that is reminiscent of the fruit it comes from .

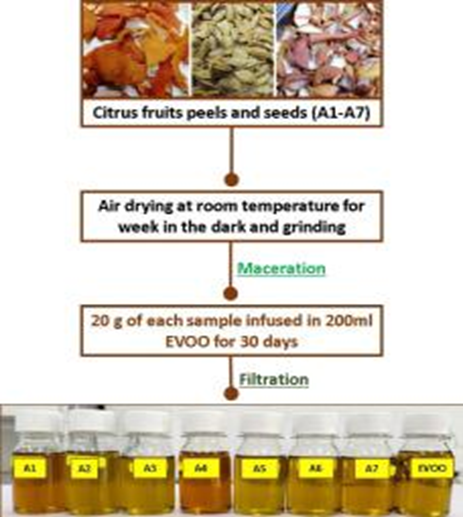

Method and preparation of olive oil and citrus peels ------

Glutamate Dispersant Kalichem (Brescia, Italy) graciously provided the olivoil. A.C.E.F. bought Sweet Almond Oil USP, Ceteareth 25, and Xantan gum. We procured dl-?-Tocopheryl Acetate from Roche, located in Milan, Italy. The following materials were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany): rutin, oleuropein, hesperidin, naringin, apigenin, sodium nitrite, aluminum chloride, sodium hydroxide, gallic acid (GA), L-ascorbic acid, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) for chemical analyses, sodium dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), trypan Bleu dye solution (0.4% v/v), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-3,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and glycerol. The Company Medi Mais Calabra of Corigliano-Rossano (Cosenza, Italy) kindly supplied clementine peels that were extracted from industrial processing waste. A nearby industry supplied the bergamot wastewater and olive leaves from Olea europea. Dulbecco’s Eagle, Modified Fetal bovine serum, medium, and a solution of penicillin (100 UI/mL)-streptomycin (100 µg/mL The supplier of the solution (1% v/v, 100 µg/mL) was S.I.A.L. Group (Rome, Italy). GIBCO (Invitrogen Corporation, Giuliano Milanese, Milan, Italy) is the supplier of trypsin/EDTA 1×. “Istituto Zooprofilattico di Modena e Reggio Emilia” (Modena, Italy) donated the NCTC244 cells. Since all of the study’s components and solvents were of an analytical grade, no additional purification procedures are needed.

2.2 Olive oil and citrus peels

The clementine waste material was used as given, however the olive leaves were separated from the wooden twigs individually, cleaned, dried, and ground with a mortar before the extractive treatments were carried out. Using 90 g of raw material for each extraction, the extracts were produced using a supercritical CO2 extractor (SFE Process—SFE 100 mL—Tomblaine, France). The temperature of the extraction vial was set at 40 °C, and the chiller was set between 0 and 5 °C. 600–800 g of CO2 were used in each extraction, with the CO2 pressure maintained at approximately 250 bar. Ethanol was utilized as the co-solvent, flowing at a rate of 20 mL/min to collect the extracts. Compared to carbon dioxide, each extraction process required around 20% w/v of ethanol.[19]

2.3. Total Phenolic Content

With a few minor adjustments, the extracts’ polyphenolic profile—which included hydrolysable tannins—was achieved in accordance with earlier literature descriptions [30]. In summary, 500 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent, 1 mL of sodium carbonate (5% w/v), and 100 µL of extract were combined. After vortexing and 25 minutes of dark incubation, the resulting mixtures’ absorbance (Abs) was measured at 760 nm wavelength (?). The reference molecule, gallic acid, was utilized at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 mg/mL. In the end, the extract’s total phenolic[20]

2.4. Flavonoid Content

A recently reported colorimetric method was used to quantify the TFC in the extracts [30]. In summary, 120 µL of aluminum chloride (10% w/v) and 60 µL of sodium nitrite solution (5% w/v) were incubated with 1 mL of the appropriately diluted sample. The sample was incubated for 5 minutes, and t Total hen 0.40 mL of sodium hydroxide (1 M) was added to balance its pH. Every sample had a final volume of 2 milliliters. Using a combination of standard flavonoid molecules with similar weight ratios, an appropriate calibration curve was generated.[21]

2.5. Antioxidant Activity of the Extracts

Using a DPPH assay, we were able to determine the antioxidant activity of our extracts, which we then expressed as the inhibition percentage of free radicals (I%), as is customary [22]. The positive and negative controls were L-ascorbic acid solution (5 mg/mL) and DPPH solution, respectively. For the analyses, methanol was utilized as a blank. The following formula was used to compute the percentage of radical scavenging activity:

1% = ((A0 – A1)/A0) × 100 1),

where A0 represents the absorbance of the negative control and A1 represents the absorbance of the extracts/standards. The percentage was normalized as a function of the extracts’ concentrations.

5. Evaluation of Ointment’s Physical Characteristicsrely

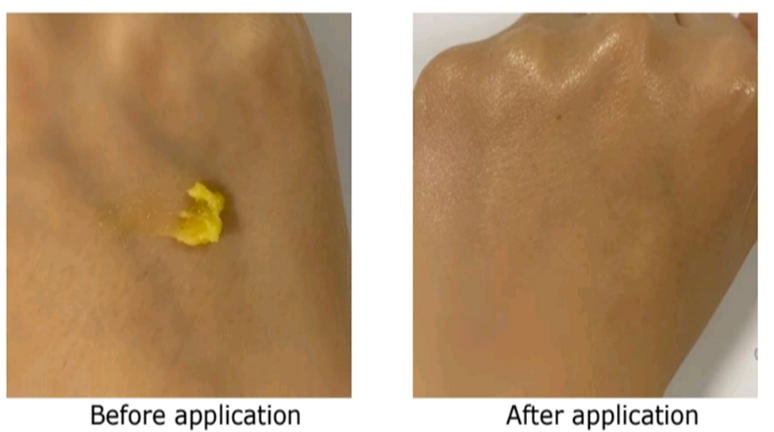

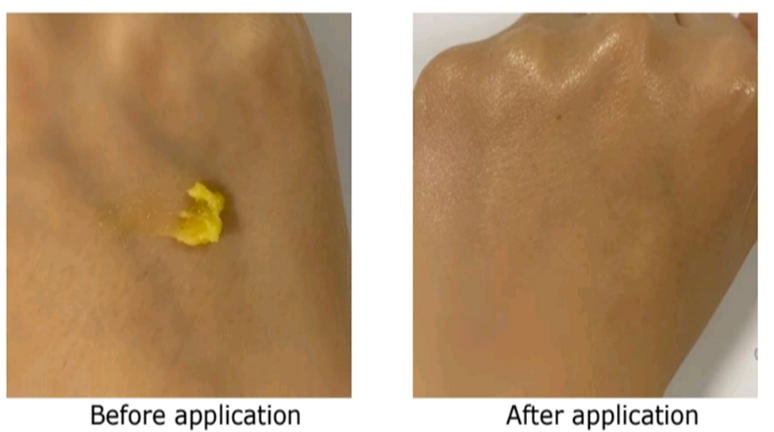

on the specific citrus peels and seeds utilized. 3.5.1 Organoleptic test results for olive oil ointment infused with lemon peellighter in hue than the peels of orange and tangerinesThe olive oil ointment with sensory infusion is referred to as having organoleptic features (Figure 4). An appealing blend of citrus fruit flavor, texture, and aroma characterize a product’s aroma, which encompasses all of its visual aspects[23]. The citrus notes in the EVOO-infused citrus and olive oil are more generated from peel-based ointments, with a significant organoleptic effect. The balance of citrus flavors and the quality of the olive oil, along with the addition of citrus peel for a hint of citrus, determine the main characteristics of the taste. The tart and sugary

6.Homogeneity test

The amount of the ointment is visually assessed by looking for color homogeneity and the lack of lumps and grains. In order to determine whether all of the basic ingredients for the ointments made

from EVOO-infused citrus peels and seeds have been blended uniformly, a homogeneity test is conduct The test’s findings demonstrated this.[24]

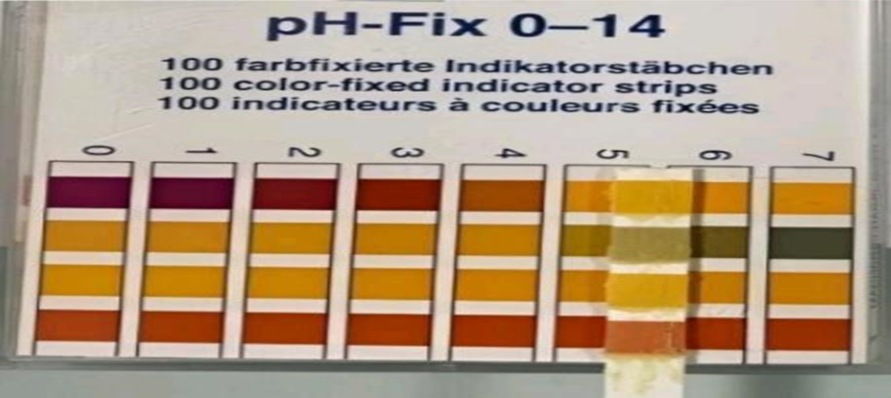

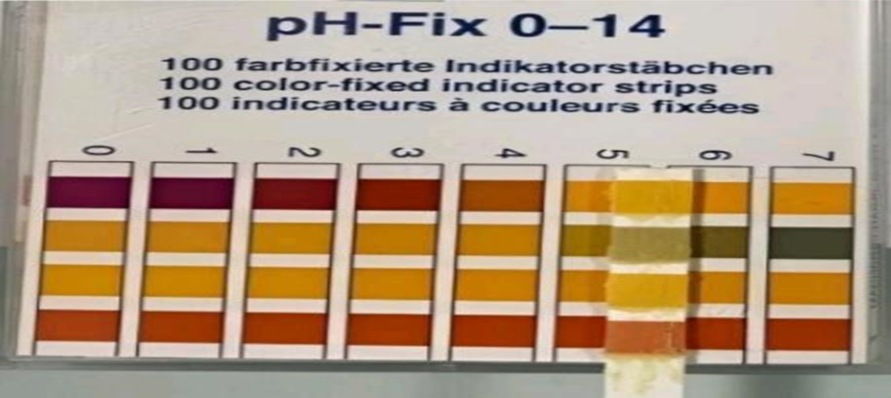

PH TEST--. Ointments’ physical characteristic”, such as viscosity and spreadability, can also be impacted by their pH test results. It’s critical to keep an eye on ointments’ pH level for ”he stability, effectiveness, and safety of ointments can be compromised by pH variations. It is a consistent feature that can influence how it is applied and Is crucial to the efficacy of regulations and quality assurance. The formula compliance’s pH values. Ointments usually have a pH of 5 to 6, which is the range that the skin commonly has (Figure 6).Keeping the pH level between 5 and 6 (30), which is good hi alignment with the typical pH of the skin’s surface, is essential for the skin’s barrier function and assists Thus, our findings can be regarded as satisfactory and stop the introduction of danger

Preparation of Proposed Face Creams

Quali-quantitative composition of prepared formulation

|

Formulation

|

Phase

|

Inci Name

|

Concentrations %(W/W)

|

|

|

A

|

Prunus Amygdalus Dulcis (Sweet Almond) Oil

Olivoil Glutamate Emulsifier G-PF

Tocopheril Acetate

Cetyl Alcohol

|

10.5

15

1

2

|

|

Empty

|

B

|

Bergamot wastewater

Xantan Gum

Glycerin

|

67.5

0.2

3.6

|

|

|

C

|

Imidazolidinyl Urea

|

0.2

|

|

|

A

|

Prunus Amygdalus Dulcis (Sweet Almond) Oil

Olivoil Glutamate Emulsifier G-PF

Tocopheril Acetate

Cetyl Alcohol

|

9.5

15

1

2

|

|

2% CPE-OLE

|

B

|

Bergamot wastewater

Xantan Gum

Glycerin

|

66.5

0.2

3.6

|

|

|

C

|

Imidazolidinyl Urea

Olive leaf extract

Clementine peel extract

|

0.2

0.5

1.5

|

|

|

A

|

Prunus Amygdalus Dulcis (Sweet Almond) Oil

Olivoil Glutamate Emulsifier G-PF

Tocopheril Acetate

Cetyl Alcohol

|

9

15

1

2

|

|

3% CPE-OLE

|

B

|

Bergamot wastewater

Xantan Gum

Glycerin

|

66

0.2

3.6

|

|

|

C

|

Imidazolidinyl Urea

Olive leaf extract

Clementine peel extract

|

0.2

0.5

2.5

|

|

|

A

|

Prunus Amygdalus Dulcis (Sweet Almond) Oil

Olivoil Glutamate Emulsifier G-PE

Tocopheril Acetate

Cetyl Alcohol

|

1

15

1

2

|

|

4%CPE-OLE

|

B

|

Bergamot wastewater

Xantan Gum

Glycerin

|

65

0.2

3.6

|

|

|

C

|

Imidazolidinyl Urea

Olive leaf extract

Clementine peel extract

|

0.2

0.3

3.5

|

Stability Studies

Using a Turbiscan Lab® (Formulaction, L’Union, France), the long-term stability of emulsions was studied [35]. Samples were placed into cylinder-shaped glass vials, and changes in the transmission (?T) and backscattering (?BS) profiles were noted over time. Data were gathered for one hour at 25 ± 1 °C and 40 ± 1 °C. Plotting of the ?T and ?BS measurements showed mean values plus or minus standard deviation. Using Turbiscan Lab®, the diameter kinetics profiles of the formulations were also examined and presented as a function of time. Turbiscan Stability Index (TSI) values were used to estimate the destabilization kinetic profiles of emulsions, and several formulations were examined [36].

Microscopy Studies

The structure of the emulsions was examined using a Morphologi G3-S microscope fitted with a Nikon® CFI 60 Brightfield/Darkfield optical system. Water was used to dilute each emulsion to a concentration of around 5 mg/mL. A drop of the diluted sample was then applied on a slide using a cover slip (20 × 20 mm, Syntesys, Padova, Italy). 20× magnification microscopies were conducted, and Morphologi software v. 8.30 (Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK) was used to export images as TIFF.

In Vivo Studies on Healthy Human Volunteers

Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL)

16 healthy human volunteers (mean age 27 ± 9) were used to test the skin acceptability of the formulations using a C+ K Multi Probe Adapter fitted with a Tewameter® TM300 probe (Courage & Khazak, Cologne, Germany). This probe measures transepidermal water loss (TEWL), a globally recognized indicator of any disruption to the skin water barrier, using two pairs of sensors to measure temperature and humidity [37]. After being briefed on the experimental methods, volunteers spent 20 minutes in a day surgery room with temperature control (24 ± 1 °C and 40%–50% relative humidity). Volunteers were enrolled in the study and given a circular template (1 cm2) to mark five places on their wrists after providing written consent. The locations were marked on areas of skin free of comedones and discolorations.

Sites were kept at least 2 centimeters apart to prevent interference from different formulations. As a negative control, 200 µL of saline solution was applied to the first location. 200 mg of the inert formulation were used to treat the second location. 200 mg of formulations containing both OLE and CPE (2%, 3%, and 4% OLE-CPE Formulations) were applied to the final three sites. TEWL values were reported as g/h·m2 and recorded 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours after application.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of the Extracts

The chemical profile and antioxidant activity of the extracts produced using supercritical CO2 were characterized through the application of several analytical techniques. The outcomes of each analysis are enumerated and condensed he antioxidant capacity of the olive leaf extracts was found to be 23.23 ± 1.47%I, with a total phenolic content of 0.0903 ± 0.0035 mg/mL (GAE) and a flavonoid concentration of 0.2164 ± 0.762 mg/mL. In contrast, the clementine waste extracts had an antioxidant activity of 25.86 ± 3.07%I, with gallic acid-like polyphenols equivalent to 0.330 ± 0.017 mg/mL GAE and a flavonoid content of 0.8844 ± 0.0796 mg/mL (Table 2). It’s interesting to note that the antioxidant activity levels of the two extracts nearly overlapped, even though the phenolic and flavonoid contents of the CPE were three and four times higher, respectively, than those of the OLE. The variations in the molecules’ chemical structures found in the extracts provide an explanation for the observed outcomes. Antioxidant activity .

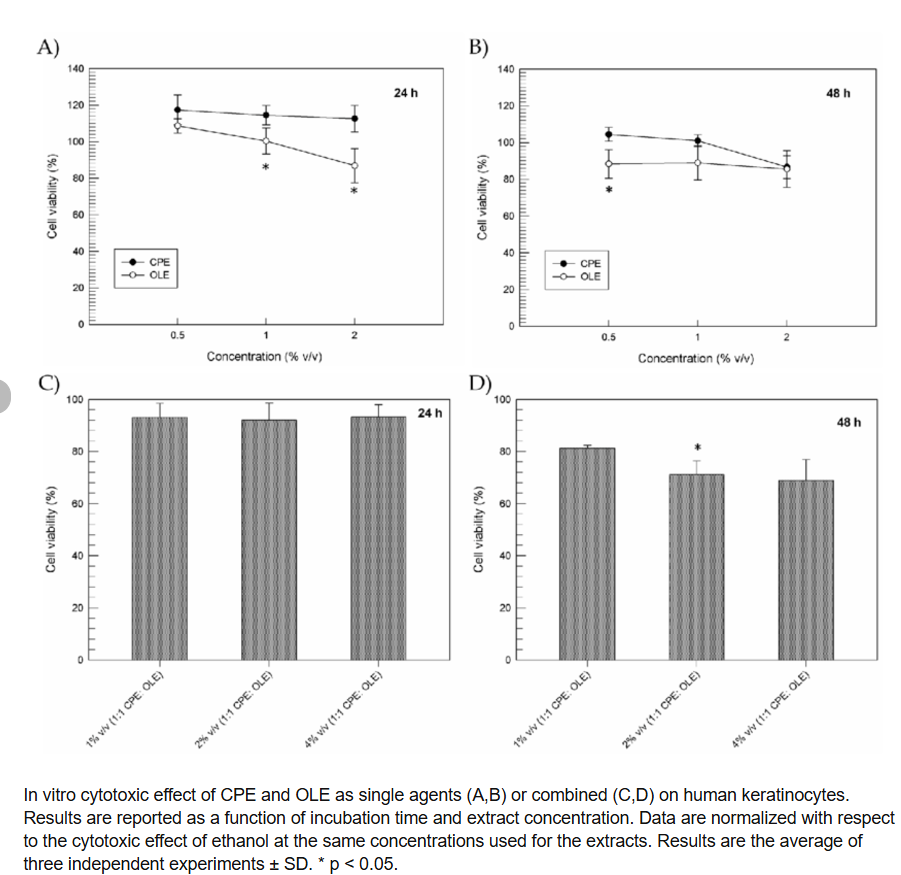

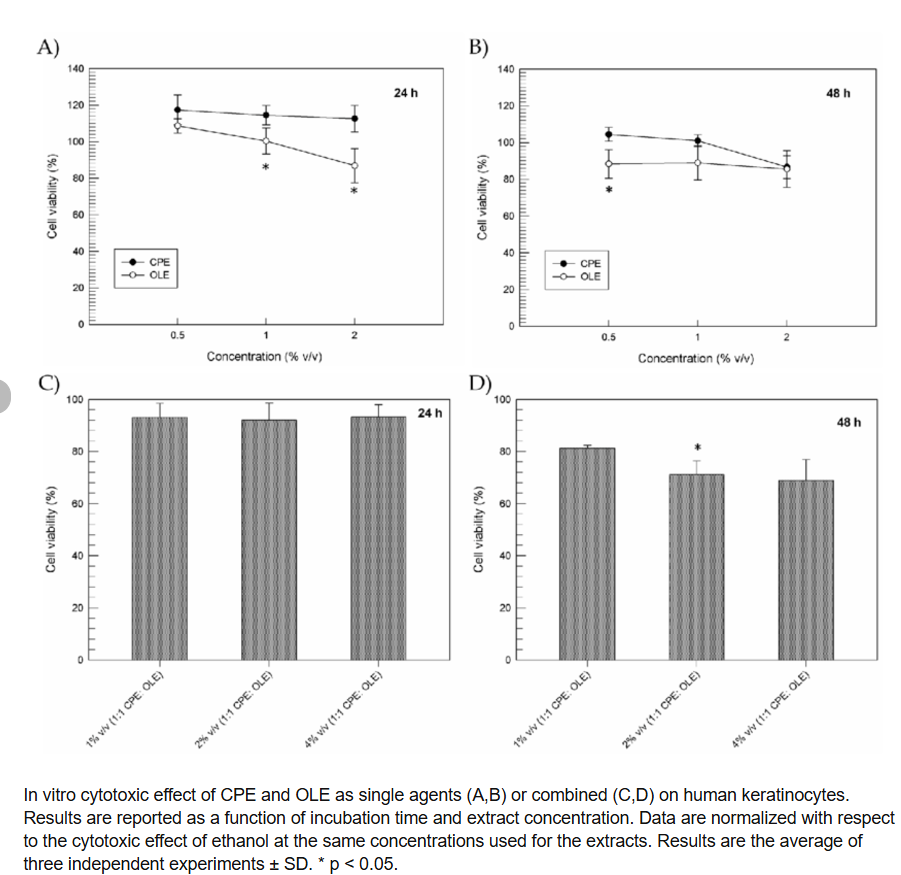

Vitro Cytotoxic Effects

We were able to identify cellular metabolic activity as a sign of cell viability, proliferation, and cytotoxicity using the MTT cell proliferation assay [46]. Even at the highest concentration tested (2% w/v), Figure 1A,B demonstrates that CPE and OLE alone do not cause any appreciable variation in the cell viability percentages of normal keratinocytes after up to 48 hours. In fact, for every sample examined, cell viability rates more than 80% were noted. At the various concentrations examined, CPE also shown a slight pro-proliferative impact up to 24 hours after treatment. The pro-proliferative impact of green tea and spirulina platensis extracts on human cells, as previously described by Chung J.H. et al. and Gunes S. et al., respectively, is in excellent accord with these data. The outcomes of a combined treatment employing CPE and OLE at Increasing final concentrations (1-4 % v/v, 1:1 ratio) are displayed in 1C and 1D. It is evident that neither extract alone nor in combination had any appreciable cytotoxic effects on human keratinocytes, maintaining values over 90% for up to 24 hours following treatment and demonstrating the high degree of safety of the studied extracts (Figure 1C). Formulation 1% v/v (1:1 CPE:OLE) ensured a high safety profile even 48 hours after the cells were exposed, although decreased cell viability percentages (~70%) were recorded at higher extract concentrations (final concentrations 2% or 4%). Certain substances found in olive leaf extracts, such as oleeuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and oleocanthal, may be responsible for this action since they can obstruct the mechanisms involved in cell growth.

The organic acids contained in CPE, i.e., citric acid, could alter the stability of these compounds as well as causing combined effects on oxidative stress and increased cytotoxic effects. For this reason, OLE was kept at 0.5% v/v in all the realized emulsions in order to exploit beneficial effects, thus preventing cytotoxic effects.

In-Depth Characterization of Empty and Citrus and Olive Leaf Extracts-Loaded Face Creams

An ideal face cream formulation was selected for the cosmetic use of natural extracts derived from olive leaves as waste material and clementine peel from industrial processing waste. Based on the homogenization and emulsification of their constituent parts, an uncomplicated laboratory procedure was used to generate the empty formulation and, as a result, the formulations loaded with citrus and olive leaf extracts (CPE-OLE). We were able to obtain O/W emulsions with good apparent spreadability, pleasing look and smell, and apparent stability thanks to the composition of the formulations. In order to conduct a more thorough and scientific characterization of all the created emulsions, a microrheological, dynamic rheological, and stability examination was conducted. An additional objective was to assess the potential effects that higher proportions of natural extracts could have on and

3.3.1. Microrheological Investigation of Empty and Clementine Peels and Olive Leaf Extracts-Loaded Face Creams

Using the Rheolaser MasterTM (Formulaction, Alfatest, Milano, MI, Italy) and diffuse wave spectroscopy, all formulations were microrheologically characterized. This method defines the viscoelastic properties of the sample by taking use of the Brownian motion of the particles therein. The samples were put into appropriate glass vials (20 mL for each sample), and throughout the whole analysis period (1 h), the light intensity was observed. We were able to acquire some microrheological characteristics of the examined materials, including the solid liquid balance (SLB), elasticity index, and mean square displacement (MSD), thanks to the software RheoSoft Master 1.4.0.0.

Stability Studies on Emulsions

The long-term stability of the emulsions was examined utilizing the multiple light scattering method of Turbiscan Lab®. The addition of OLE and CPE during the preparation stage did not impair the excellent stability profiles that any of the formulations showed. Regardless of the amount of extracts used, the values of ?T and ?BS (Figure S1) were always within ±2%, demonstrating the lack of any creaming, flocculation, or sedimentation phenomena [60]. TSI assays, which demonstrated that there were no appreciable differences in TSI values between the formulations with OLE and CPE and the empty formulation, further supported this conclusion.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we suggested using olive leaf extracts and clementine peels as high-value, food waste-derived components for face cream. Using a carbon dioxide supercritical fluid extraction approach, extracts were produced that had an antioxidant activity of about 25% and other appropriate properties. These components produce stable creams when added to the suggested cosmetic, as shown by Turbiscan analyses conducted at room temperature and under severe storage conditions (i.e., 25 and 40 °C, respectively). With extract concentrations ranging from 1 to 2% v/v, both extracts showed safe profiles in vitro on NCTC human keratinocytes, with no discernible cytotoxic effect after up to 48 hours of incubation. The resultant face creams containing extracts of olive leaves and clementine peel shown appropriate spreadability and pseudoplastic properties.

Positive response from volunteers in good health verified the cosmetic formulations’ prospective applications, as the OLE-CPE formulations were described as having a decent texture, a pleasant scent derived from bergamot wastewater, and a sufficiently spreadable consistency. The suggested strategy emphasizes the recycling of food waste byproducts as ingredients in the beauty industry in order to create a circular economy that can provide biomaterials with added value while lowering resource depletion and environmental effects

REFERENCES

- H ang, C.-H.; Liu, S.-M.; Hsu, N.-Y. Understanding global food surplus and food waste to tackle economic and environmental sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Chiu, S.-Y.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Lu, L.-C.; Huang, K.-Y. Agricultural production efficiency, food consumption, and food waste in the European countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Reddy, C.N.; Reddy, S.D.M.; Mandal, S.K.; Yadavalli, R.; Sarma, H. Valorization of agro-industrial biowaste to biomaterials: An innovative circular bioeconomy approach. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossReaf

- Nath, P.C.; Sharma, R.; Debnath, S.; Nayak, P.K.; Roy, R.; Sharma, M.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Sridhar, K. Recent advances in production of sustainable and biodegradable polymers from agro-food waste: Applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicines. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrapani, G.; Zare, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Biomaterials from the value-added food wastes. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 19, 101181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef

- Morganti, P.; Gao, X.; Vukovic, N.; Gagliardini, A.; Lohani, A.; Morganti, G. Food loss and food waste for green cosmetics and medical devices for a cleaner planet. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef

- Ghasemi A, Gorouhi F, Rashighi-Firoozabadi M, Jafarian A, Firooz A. Striae gravidarum: associated factors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21(6):743-6.

- W.B. Dunham, E. Zuckerkandl, R. Reynolds, R. Willoughby, R. Marcuson, R. Barth and L. Pauling. Effects of intake of L-ascorbic acid

- S. Englard and S. Seifter. The Biochemical Function of Ascorbic Acid Annu. Rev. Nutr. 6: 365-406 (1986).

- W.P. Smith. Barrier disruption treatments for structurally deteriorated skin. US Patent 5720963 (1998

- A.M. Klingman. Hydrating injury to human skin. In: P.G.M. Vander Valk, H.I. Maibach, Eds. The irritant contact dermatitis syndrome. CRC press Inc, Boca Raton; 187-194 (1996).

- Vouyiouka, S.; Theodoulou, P.; Symeonidou, A.; Papaspyrides, C.D.; Pfaendner, P. Solid state polymerization of poly(lactic acid): Some fundamental parameters. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 2473–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzinos, I.; Salta, F.; Yannakopoulou, K.; Chiou, A.; Karathanos, V.T. Encapsulation of olive leaf extract in ?-Cyclodextrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8088–8094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, A.C.; Paiva, J.P.; Diniz, R.R.; Dos Anjos, V.M.; Silva, A.B.S.; Pinto, A.V.; Dos Santos, E.P.; Leitão, A.C.; Cabral, L.M.; Rodrigues, C.R. Photoprotection assessment of olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves extract standardized to oleuropein: In vitro and in silico approach for improved sunscreens. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 193, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, E.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E.; Madrid, Y. Citrus peels waste as a source of value-added compounds: Extraction and quantification of bioactive polyphenols. Food Chem. 2019, 295, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.L.; Gondim, S.; Gómez-García, R.; Ribeiro, T.; Pintado, M. Olive leaf phenolic extract from two Portuguese cultivars–bioactivities for potential food and cosmetic application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporini, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Sicari, V.; Pellicanò, T.M.; Reitano, A.; Dugay, A.; Deguin, B.; Tundis, R. Citrus× clementina Hort. Juice enriched with its by-products (peels and leaves): Chemical composition, in vitro bioactivity, and impact of processing. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevete, G.; Carvalho, L.G.; del Carmen Razola-Diaz, M.; Verardo, V.; Mancini, G.; Fiore, A.; Mazzonna, M. Ultrasound assisted extraction and liposome encapsulation of olive leaves and orange peels: How to transform biomass waste into valuable resources with antimicrobial activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 102, 106765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Uribe, E.; López, J.; Contreras, D.; Poblete, J. A study of dried mandarin (Clementina orogrande) peel applying supercritical carbon dioxide using co-solvent: Influence on oil extraction, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant activity. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Márquez, J.M.; Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Varela-López, A.; Puentes, J.G.; Pino-García, R.D.; Sánchez-González, C.; Elio, I.; Battino, M.; García, R. Exploring the antioxidant, neuroprotective, and anti-inflammatory potential of olive leaf extracts from Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Italy. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanitphakdeedecha, R.; Ng, J.N.C.; Junsuwan, N.; Phaitoonwattanakij, S.; Phothong, W.; Eimpunth, S.; Manuskiatti, W. Efficacy of olive leaf extract–containing cream for facial rejuvenation: A pilot study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1662–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qabaha, K.; Al-Rimawi, F.; Qasem, A.; Naser, S.A. Oleuropein is responsible for the major anti-inflammatory effects of olive leaf extract. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillich, O.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Eisner, P.; Kerscher, M. Polyphenols as active ingredients for cosmetic products. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2015, 37, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.V.; Pintado, M. Hesperidin from Orange Peel as a Promising Skincare Bioactive: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mare, R.; Pujia, R.; Maurotti, S.; Greco, S.; Cardamone, A.; Coppoletta, A.R.; Bonacci, S.; Procopio, A.; Pujia, A. Assessment of Mediterranean Citrus Peel Flavonoids and Their Antioxidant Capacity Using an Innovative UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Approach. Plants 2023, 12, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef

- R.; Maurotti, S.; Ferro, Y.; Galluccio, A.; Arturi, F.; Romeo, S.; Procopio, A.; Musolino, V.; Mollace, V.; Montalcini, T. A rapid and cheap method for extracting and quantifying lycopene content in tomato sauces: Effects of lycopene micellar delivery on human osteoblast-like cells. Nutrients 2022, 14, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Souto EB, Fangueiro JF, Fernandes AR, Cano A, Sanchez-Lopez E, Garcia ML, Etal. Physicochemical and biopharmaceutical aspects influencing skin permeation and role of SLN and NLC for skin drug delivery. Heliyon [Internet]. 2022 Feb;8(2):e08938. Available from: .

- Luo, M.; Qi, X.; Ren, T.; Huang, Y.; Keller, A.A.; Wang, H.; Wu, B.; Jin, H.; Li, F. Heteroaggregation of CeO2 and TiO2 engineered nanoparticles in the aqueous phase: Application of turbiscan stability index and fluorescence excitation-emission matrix (EEM) spectra. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 533, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef

- López-García, J.; Lehocký, M.; Humpolí?ek, P.; Sáha, P. HaCaT keratinocytes response on antimicrobial atelocollagen substrates: Extent of cytotoxicity, cell viability and proliferation. J. Funct. Biomater. 2014, 5, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Shubhangi Shete*

Shubhangi Shete*

Anil Jadhav

Anil Jadhav

Dr. Kawade Rajendra

Dr. Kawade Rajendra

10.5281/zenodo.14273534

10.5281/zenodo.14273534