Abstract

Introduction: The use of Ocimum sanctum (holy basil, tulsi) from Lamiaceae family and Zingiberofficinale (ginger, adrakh) from Zingiberaceae is quite common in day to day life of Indian families.Ocimum sanctum (tulsi) from Lamiaceae family and Zingiberofficinale (ginger) from Zingiberaceae has been widely used for thousands of years in Ayurveda and Unani systems to cure or prevent a number of illnesses. The objective is to investigate, formulate as well as evaluate the synergistic effect of O. sanctum (Tulsi) and Z. officinale (ginger) by its succesive extraction. Coagulation activity of O. sanctum and Z. officinale was measured by in-vivo and in-vitro prothrombin time determination method on blood samples. Material And Method: The raw plants were subjected to successive extraction process followed by its in vitro and in vivo prothrombin time determination. The optimized extracts were combined and used for formulation and evaluation of liquid dosage formulation. Result: The extracts B2 and G3 were found to have best results. Conclusion: Finding led to the conclusion that O. sanctum leaves and Z. officinale rhizomes may act as an anticoagulant and thus, potentially may replace the current conventional anticoagulant drugs. Therefore, the work opens chances of new discoveries on future prospective. The investigation and development of new formulation in oral or parenteral route can be done for herbal anticoagulation therapy.

Keywords

Anticoagulant, Prothrombin Time Ocimum sanctum and Zingiber officinale.

Introduction

The use of plants as remedies for various ailments has formed the basis of our modern medicinal sciences (Hutchings et al., 1996). Plant extracts can be an alternative to currently used antiplatelet agents, as they constitute a rich source of bioactive chemicals. The phytochemicals from herbal plants are found to have biological activities such as anticoagulant properties. Compounds such as alkaloids, xanthones, coumarins, anthraquinones, flavonoids, stilbenes, and naphthalenes have been reported to have an effect on platelet aggregation (Aburjai, 2000; Chen et al., 2001; Chung et al., 2002). Furthermore, polyphenol-rich diets have been shown to be beneficial in vascular functioning including platelet aggregation in humans. Therefore, the use of herbal medicine provides an alternative to overcome the limitations of available anticoagulants such as warfarin and heparin which have bleeding complication, as well as uncertainty of the newer anticoagulant drugs dosing in some patient populations such as patient with underlying chronic diseases (Akremi N et al., 19982-1988). The plants which have anticoagulant properties are ginkgo, ginseng, willow, garlic, ginger, horse chestnut, alfafa, clover, rue anise, meadowsweet, sen, fenugreek, agrimony, onion, fennel, grapefruit, holy basil, soyabean, thyme, orangano, cauliflower, green tea, currant, carrot, celery, liquorice, banana tree, pineapple, parsley, papaya, boldo, cinnamon, basil, etc. The plants chosen here are Ocimum sanctum L. (basil) and Zingiber officinale (ginger). The use of Ocimum sanctum (holy basil, tulsi) from Lamiaceae family and Zingiberofficinale (ginger, adrakh) from Zingiberaceae is quite common in day to day life of Indian families.Ocimum sanctum (tulsi) from Lamiaceae family and Zingiberofficinale (ginger) from Zingiberaceae has been widely used for thousands of years in Ayurveda and Unani systems to cure or prevent a number of illnesses. Both plants have been studied individually on anticoagulant parameters and have positive effects. The objective is to investigate, formulate as well as evaluate the synergistic effect of O. sanctum (Tulsi) and Z. officinale (ginger) by its succesive extraction. Coagulation activity of O. sanctum and Z. officinale was measured by in-vivo and in-vitro prothrombin time determination method on blood samples.

MATERIAL AND METHODOLOGY

Collection and Authentication: Leaves of Ocimum sanctum L. (basil) were collected from local garden of IFTM University campus, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, washed with sterile water and dried in shades. Then the samples were powered in mechanical grinder. Rhizomes of Zingiber officinale (ginger) were purchased from local market of Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, washed with sterile water and dried in shades. Then the samples were powered in mechanical grinder. The plants were examined by Prof. Nawal Kishore Dubey (FNASc, FNAAS, Centre of Advanced Study in Botany, Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005.

Extraction: The powdered material of Ocimum sanctum and Zingiber officinale was extracted simultaneously by successive extraction methods with petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate, ethanol and water in the increasing order of their polarity. A known amount of powdered material (200gm) of Ocimum sanctum and Zingiber officinale was taken in two separate assemblies simultaneously. The powdered material was subjected to soxhlet extraction and exhaustively extracted with respective solvents for about 48 hours. The extracts were filtered and concentrated in vacuum under reduced pressure using rotary flash evaporator and dried in the dessicator. The solvent was removed under pressure to obtain a total extracts. Yield of extract in each solvent was recorded by weighing extract in pre weighed container and taking the difference. The percentage yield of each extracts was calculated using the following formula:

Percentage yield = Final weight of the dried extract X 100 Initial weight of the powder

All the extracts were kept in separate vials in the refrigerator till further use.

In-Vitro Prothrombin Time Test: Each sample of extracts was taken individually for in-vitro prothrombin time test. Centrifuge tubes were taken and trisodium citrate was added in it. Three milliliters of blood sample was taken and added to centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 min. with the help of micropipettes, plasma was separated and saved in eppendorf tubes. 250 µL of plant extract and 250 µL of platelet poor plasma were mixed in eppendorf tube and sample were incubated at 37oC for 5 min.100 µL of test plasma and 200 µL of Thromborel S reagent was added and clotting time was measured as prothrombin time (Lang Ma et al 2019).

Optimization: The action of making the best or most effective use of a situation or resource is known as optimization. The best two samples from the two plants were selected on the basis of the in-vitro prothrombin time test. Optimization was done on the basis of INR ratio for anticoagulant i.e., 2-3, and later was used for further formulation development.

Formulation Development: For prepation of simple syrup, 666.7 g of Sucrose was weighed and taken in three different containers. Purified water was added and heated until it dissolved with occasional stirring. Sufficient boiling water was added to produce 1000 ml. Different concentration (10 ml, 20 ml and 30ml) of extracts (on basis of in-vitro prothrombin time test ) was taken and mixed with the prepared syrups. Required quantity of Sodium benzoate (0.2%) was added as preservative to the above mixture. Solubility was checked by observing the clarity of solution visually. The final herbal syrup was then subjected for evaluation.

Evaluation

Color examination: 5 ml final syrup was taken into watch glasses and placed against white back ground in white tube light. It was observed for its color by naked eye.

Odor examination: 2 ml of final syrup was smelled individually. The time interval among two smelling was kept 2 minutes to nullify the effect of previous smelling.

Taste examination: A pinch of final syrup was taken and examined for its taste on taste buds of the tongue.

Determination of pH: Placed an accurately measured amount 10 ml of the final syrup in a 100 ml volumetric flask and made up the volume up to 100 ml with distilled water. The solution was sonicated for about 10 minutes. pH was measured with the help of digital pH meter.

Specific gravity at 25oC: A thoroughly clean and dry Pycnometer was selected and calibrated by filling it with recently boiled and cooled water at 25oC and weighing the contents. Assuming that the weight of 1 ml of water at 25oC when weighed in air of density 0.0012 g/ml was 0.99602 g. The capacity of the Pycnometer was calculated. Adjusting the temperature of the final syrup to about 20oC and the Pycnometer was filled with it. Then the temperature of the filled Pycnometer was adjusted to25oC, any excess syrup was removed and weight was taken. The tare weight of the Pycnometer was subtracted from the filled weight. The weight per milliliter was determined by dividing the weight in air, expressed in g, of the quantity of syrup which fills the Pycnometer at the specified temperature, by the capacity expressed in ml, of the Pycnometer at the same temperature. Specific gravity of the final syrup was obtained by dividing the weight of the syrup contained in the Pycnometer by the weight of water contained, both determined at 25oC.

Viscosity: Viscosity of the formulation was measured by using Ostwald viscometer.

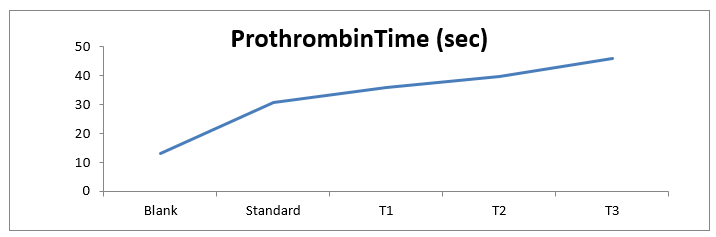

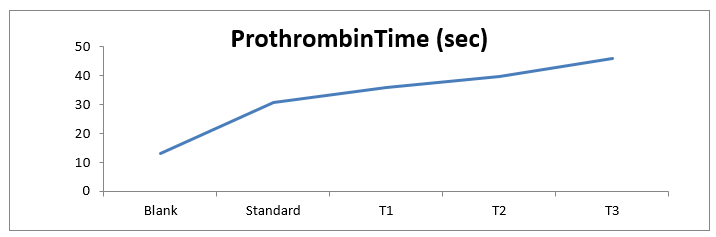

In-Vivo Prothrombin Test: Animals were divided into five groups with 6 rats in each group. 1st group received simple syrup and served as control group for 2 months; 2nd, 3rd and 4th group were administered orally with low, medium and high dose of optimized formulation. 5th group received aspirin as standard drug 150 mg/kg once in a day for 6 days/week. 3 ml of blood samples were drawn prior to 6 h fasting at day 30th in centrifuge tubes with trisodium citrate added in it and centrifugated at 3000 rpm for 5 min. With the help of micropipettes, plasma was separated and saved in eppendorf tubes. 100µL of test plasma and 200 µL of Thromborel S reagent was added and clotting time was measured as prothrombin time (Lang Ma et al 2019).

Dissolution study: The test was performed according to USP (type 2) at 37 °C and 75 rpm. Syrup was held in different vessels (1000 mL). The syrup sample (5 mL) was taken using a syringe and quantitatively transferred to the vessel at the top of the dissolution medium. To calculate the exact weight of syrup added to the vessel, the syringe was weighed at three stages: empty, filled with the syrup, and after the sample was expelled into the dissolution vessel. Aliquots were removed from the vessel and replaced with fresh dissolution medium (PBS) at predetermined time intervals. For rapidly dissolving products including syrup, aliquots were removed at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 20, 40 and 60 min for the syrup. The absorbance was recorded at different time interval.

RESULTS

Table 1 Percentage Yield of Holy Basil Extract

|

S. No.

|

Sample

|

Initial weight

|

Final weight

|

Percentage yield

|

|

1

|

B1(chloroform)

|

200 gm

|

8.2 gm

|

4.1

|

|

2

|

B2 (pet. ether)

|

200 gm

|

5.5 gm

|

2.75

|

|

3

|

B3 (ethyl acetate)

|

200 gm

|

6.3 gm

|

3.15

|

|

4

|

B4 (ethanol)

|

200 gm

|

1.2 gm

|

0.6

|

|

5

|

B5 (water)

|

200 gm

|

5.7 gm

|

2.85

|

|

6

|

G1(chloroform)

|

200 gm

|

12.7 gm

|

6.35

|

|

7

|

G2(pet. ether)

|

200 gm

|

8.4 gm

|

4.2

|

|

8

|

G3(ethyl acetate)

|

200 gm

|

3.9 gm

|

1.95

|

|

9

|

G4(ethyl acetate)

|

200 gm

|

7.6 gm

|

3.8

|

|

10

|

G5(water)

|

200 gm

|

9.8 gm

|

4.9

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2 In-Vitro Prothrombin Test

|

S. No.

|

Sample

|

Prothrombin Time (sec)

|

|

1

|

B1

|

15.8

|

|

2

|

B2

|

37.3

|

|

3

|

B3

|

96.2

|

|

4

|

B4

|

109.3

|

|

5

|

B5

|

135.7

|

|

6

|

G1

|

40.8

|

|

7

|

G2

|

15.5

|

|

8

|

G3

|

39.8

|

|

9

|

G4

|

21.3

|

|

10

|

G5

|

76.5

|

From the above observations we found that the extracts B5 and G5 have the greatest prothrombin time value. But the INR ratio (International Normalized ratio) for prothrombin time of 1.0 or below is considered normal in a healthy person. An INR range of 2.0 to 3.0 is generally an effective therapeutic range for people taking anticoagulant for disorders such as aterial fibrillation or a blood clot. The INR ratio was calculated by using the below formula:

INR = Prothrombin Time (patient) / Prothrombin Time (normal)

Extracts B2 and G3 was found to have the best as per INR ratio.

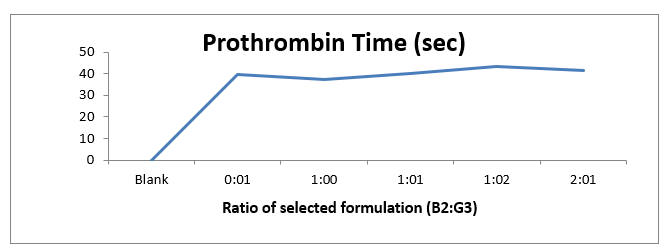

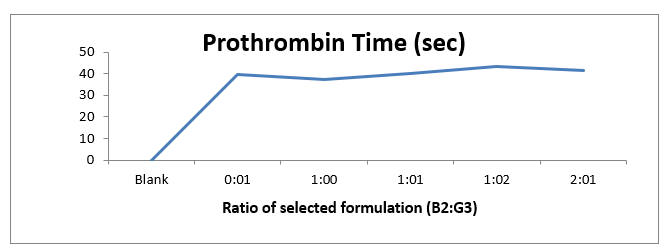

Optimization

From the in vitro prothrombin time test we found that the extracts B2 and G3 are the best as per INR ratio. Further the selected extracts were taken for optimizing the best combination in different ratio (0:1, 1:0, 1:1, 1:2 and 2:1). Optimization was done on the basis of INR ratio for anticoagulant i.e., 2-3. Ratio 1:1 (Basil:Ginger) was found to have the best prothrombin time as per INR ratio.

Table 3 Optimization

|

S. No.

|

Ratio of selected extract (B2:G3)

|

Prothrombin Time (sec)

|

|

1

|

Blank

|

11-13.5

|

|

2

|

0:1

|

39.8

|

|

3

|

1:0

|

37.3

|

|

4

|

1:1

|

40.3

|

|

5

|

1:2

|

43.2

|

|

6

|

2:1

|

41.7

|

On the basis of above data a graph has been plotted between the Ratio of selected extract (B2:G3) and Prothrombin Time. The graph depicts that the extracts shows the effective prothrombin time as compared to normal (blank) prothrombin time. The graph also shows that when ginger is mixed in greater amount the Prothrombin Time has increased. From that observation we can say that ginger has more Prothrombin Time than basil. Ratio 1:1 (Basil: Ginger) was found to have the best prothrombin time as per INR ratio. Further the extract in ratio 1:1 was taken for formulation development.

Fig 1 In-vitro prothrombin time test

Formulation Development

The optimized fomulation was prepared according to the given formula.

Rx

Sucrose 66.67 g

Purified water 100 ml

Plant extracts (T1, T2, T3)10 ml, 20 ml, 30 ml

Sodium benzoate0.2 gm

|

S. No.

|

Evaluation Parameter

|

Result

|

|

T1

|

T2

|

T3

|

|

1

|

Colour

|

Brownish yellow

|

Brownish yellow

|

Brownish yellow

|

|

2

|

Odour

|

Pleasant

|

Pleasant

|

Pleasant

|

|

3

|

Taste

|

Sweet

|

Sweet

|

Sweet

|

|

4

|

pH

|

6.2

|

6.2

|

6.2

|

|

5

|

Viscosity

|

0.14 Pa.s

|

0.14 Pa.s

|

0.15 Pa.s

|

|

6

|

Specific gravity

|

1.1722 g/ml

|

1.1722 g/ml

|

1.1722 g/ml

|

|

7

|

In-vivo prothrombin time

Blank 13 ± 2.5 sec

Standard 30.7 ± 1.8 sec

|

36 ± 2.8 sec

|

39.9 ± 5 sec

|

45.8± 4.3 sec

|

Fig 2 In-vivo prothrombin time test

Dissolution study:

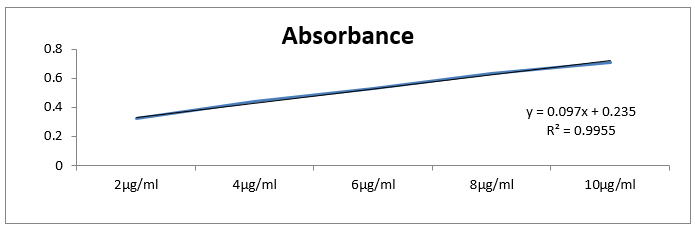

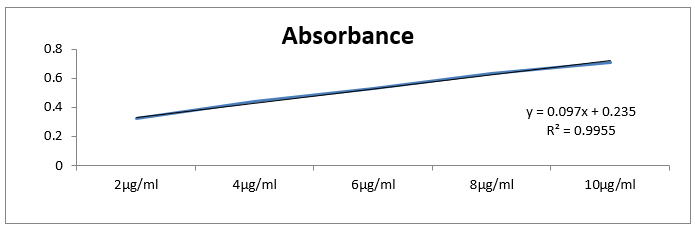

a) Standard curve of basil: ginger (1:1)

Table 5 Absorbance vs concentration

|

S. No.

|

Concentration

|

Absorbance

|

|

1

|

2µg/ml

|

0.32 ± 0.02

|

|

2

|

4µg/ml

|

0.44 ± 0.05

|

|

3

|

6µg/ml

|

0.53 ± 0.09

|

|

4

|

8µg/ml

|

0.63 ± 0.04

|

|

5

|

10µg/ml

|

0.91 ± 0.03

|

Fig3 Standard curve

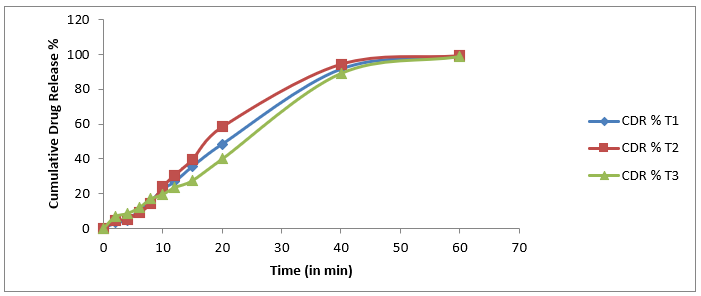

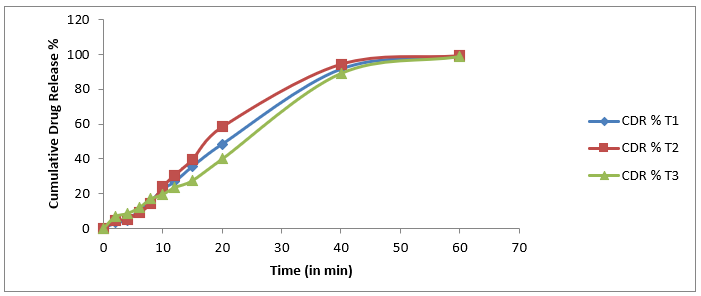

b) Drug release

Table 6 Time vs Cummulative drug release

|

S. No.

|

Time (in min)

|

Cummulative drug release %

|

|

T1

|

T2

|

T3

|

|

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1

|

2

|

3.21 ± 0.11

|

4.41 ± 0.02

|

6.8 ± 0.06

|

|

2

|

4

|

4.74 ± 0.09

|

5.42 ± 0.05

|

8.56 ± 0.09

|

|

3

|

6

|

10.39 ± 0.12

|

9.09 ± 0.07

|

11.89 ± 0.12

|

|

4

|

8

|

15.82 ± 0.03

|

14.36 ± 0.12

|

17.02 ± 0.18

|

|

5

|

10

|

22.67 ± 0.05

|

24.02 ± 0.08

|

19.58 ± 0.14

|

|

6

|

12

|

26.93 ± 0.10

|

30.70 ± 0.06

|

23.59 ± 0.19

|

|

7

|

15

|

35.72 ± 0.08

|

39.75 ± 0.09

|

27.56 ± 0.17

|

|

8

|

20

|

48.60 ± 0.15

|

58.49 ± 0.15

|

39.99 ± 0.29

|

|

9

|

40

|

91.84 ± 0.14

|

94.60 ± 0.08

|

89.33 ± 0.20

|

|

10

|

60

|

99.28 ± 0.19

|

99.53 ± 0.23

|

99.01 ± 0.27

|

Fig 4 Time vs Cummulative drug release

CONCLUSION

In this study, the synergistic effect of O. sanctum (Tulsi) and Z. officinale (ginger) from its extracts obtained from successive extraction was determined by prothrombin time determination. In this study the herbs was extracted through successive extraction method using different solvents. The prefomulation study was conducted on the obtained extracts on different parameter such as Soxhlate extraction, solubility study, chromatography and spectroscopy. Coagulation activity of O. sanctum and Z. officinale extracts was measured by in-vitro prothrombin time. From the prothrombin time (PT) test we found that B2 (pet. ether) and G3 (ethyl acetate) have the best PT time in comparison to other extracts. The optimized combnation was obtained by measuring PT time against different ratio of aqueous extract of O. sanctum and Z. officinale as follows: 0:0, 0:1, 1:0, 1:1, 1:2, 2:1. When Ocimum sanctum and Zingiber officinale was taken in 1:1 ratio the anticoagulant effect was found to be best in respect to other ratios ( 1:0, 0:1, 2:1, and 1:2). Based on the above results the formulation of polyherbal syrup and its evaluation on different parameters such as colour, odour, taste, pH, viscosity, specific gravity and in-vivo prothrombin time was done.

Future Scope:

Plants have been the origin of many of the commonly used pharmaceutical drugs worldwide, and will continue to be so in the future too. In addition, these natural substances have been used as crude medicinal preparations in different cultures to provide needed health care service to millions of people globally. During the past several decades, plant products categorized as herbal supplements have been used increasingly by various segments of the US population. The present work also takes note on the use of herbal supplements and the limitations of the herbal literature related to blood clotting, meanwhile emphasizing the need for improved regulation and further research on herbal products. The implementation of the measures outlined in the work may contribute to the provision of better health care services to patients who use herbal supplements with blood-thinning properties. In this study, we have found that the aqueous extract of O.sanctum showed anticoagulation effects in human plasma by prolongation of prothrombin time. This finding led to the conclusion that O. sanctum leaves and Z. officinale rhizomes may act as an anticoagulant and thus, potentially may replace the current conventional anticoagulant drugs. Therefore, the work opens chances of new discoveries on future prospective. The investigation and development of new formulation in oral or parenteral route can be done for herbal anticoagulation therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

The authors are thankful to Dr. Navneet Verma, IFTM University, Moradabad (U.P.) India, for availing the laboratory facilities during course of research studies.

REFRENCES

- Hutchings A, Scott AG, Lewis G, Cunningham A. (1996). Zulu Medicinal Plants ? An Inventory. University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg.

- Aburjai TA. (2000). Anti-platelet stilbenes from aerial parts of Rheum palaestinum. Phytochemistry, 55, 407–410.

- Chen JJ, Chang YL, Teng CM, Lin WY, Chen YC, Chen IS. (2001). A new tetrahydroprotoberberine N-oxide alkaloid and anti-platelet aggregation constituents of Corydalis tashiroi. Planta Med, 67, 423–427.

- Chung MI, Weng JR, Wang JP, Teng CM, Lin CN. (2002). Antiplatelet and anti-inflammatory constituents and new oxygenated xanthones from Hypericum geminiflorum. Planta Med, 68, 25–29.

- Akremi N, Aouni M, Haloui E, Fenina N, Marzouk B, Marzouk Z.Antimicrobial and anticoagulation activities of Citrullus colocynthis Schrad. leaves from Tunisia (Medenine).African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 2012, Vol. 6, pp. 1982-1988.

- Khandelwal KR (2006). Practical Pharmacognosy, Nirali Prakashan, Pune. 16: pp 9-14, 20-22, 41-44, 137-141, 161-165.

- WHO.Guidelines for the Assessment of Herbal Medicines. WHO/TRM/91.4, Geneva : s.n.; 1991.

- Ron Winslow and Avery Johnson (2007-12-10). “Race is on for next Blood Thinner”. Wall Street Journal. p. A12.

- Sectoral Study on Indian Medicinal Plants – Status, Perspectiveand Strategy for Growth, Biotech Consortium India Ltd, New Delhi, 1996.

- Akremi N, Aouni M, Haloui E, Fenina N, Marzouk B, Marzouk Z. Antimicrobial and anticoagulation activities of Citrullus colocynthis Schrad. leaves from Tunisia (Medenine). African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology.2012; 6: pp.1982-1988.

- Rehan HMS, Singh S, Majumdar DK. Effect of Ocimum sanctum fixed oil on blood pressure, blood clotting time and pentobarbitone-induced sleeping time. Journal of Ethnopharmacology.2001; 78: pp.139-143.

- TajEldin IM, MA Elmutalib, Hiba F., and Thowiba S., Elnazeer I. Hamedelniel. An in vitro Anticoagulant effect of aqueous extract of ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizomes in blood samples of normal individuals. American Journal of Research Communication.2016; vol 4(1); page.113-121.

- Choi PT, Douketis JD, Linkins LA. Clinical impact of bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med.2003; 139(11): pp.893–900.

- Kumar R., Saha P., Lokare P., Datta K., Selvakumar P., Chourasiya A. A systematic review of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi): Morphological Characteristics, Phytoconstituents and Therapeutic application. International Journal for Research in Applied Sciences and Biotechnology 2022; vol 9(2); page 221–226.

- Singh DK, Hajra PK. Floristic diversity. In Changing Perspective of Biodiversity Status in the Himalaya, Gujral GS, Sharma V, Eds. British Council Division, British High Commission Publication, Wildlife Youth Services: New Delhi, India, 1996; 23–38.

- Pandey AS, Pant MC. Changes in the blood lipid profile after administration of Ocimum sanctum leaves in normal albino rats. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacology, 1994; 38(4): P.311-312.

- Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Ocimum sanctum in Indian medicinal plants (Published by L.B Basu. Allahabad), 1965.

- Gupta SK, Prakash J, Shrivastava S. Validation of claim of tulsi Ocimum sanctum as medicinal plant. Indian J. Experimental biology, 2002; 40(7): 765-773.

- Jeba CR, Vaidyanathan R, Kumar RG. Immunomodulatory activity of aqueous extract of Ocimum sanctum in rat. Int J on Pharmaceutical and Biomed Res, 2011; 2: 33-38.

- Agarwal P., Nagesh, L. and Murlikrishnan (2010). Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of various concentrations of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) extract against Streptococcus mutans: An in vitro study.Indian J Dent Res, 21(3), 357-359.

- Akilavalli N., Radhika J. and Brindha P. (2011). Hepatoprotective activity of Ocimum sanctum linn. Against lead induced toxicity in albino rats.Asian J Pharm Clin Res, 4(2), 84- 87.

- Anuradha B., and Murugesan A.G. (2001). Immunotoxic and haematotoxic impact of Copper acetate on fish Oreochromis mossambicus and modulatory effect of Ocimum sanctum and Valairasa chendhuram. M.Sc thesis submitted to Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli.

- Aparna D., and Musarraf M.H. (2013).In vitrocytotoxic effect of methanolic crude extracts of Ocimum sanctum. IJPSR, Vol. 4(3): 1159-1163.

- Arivuchelvan S., Murugesan P., Mekala and Yogeswari R. (2012). Immunomodulatory effect of Ocimum sanctum in broilers treated with high doses of gentamicin.Indian J. Drugs Dis. 1(5), 109-112.

- G.H. (2011). Comparative study of wound healing activity of topical and OralOcimum sanctum linn in albino rats. Al Ameen J Med Sci 4 (4):3 0 9 -3 1 4.

- Babu K. and Maheswari U.K.C. (2005). In vivo studies on the effect of Ocimum sanctum.

- Baskaran X. (2008). Preliminary Phytochemical Studies and Antibacterial Activity of Ocimum sanctum L. Ethnobotanical Leaflets,12, 1236-1239.

- Jyoti S. et al., (2004). Evaluation of hypoglycemic and antiocxidant effect of Ocimum sanctum. Indian journal of Clinicla Biochemistry, 19 (2); 152-155.

- Kicel A., Kurowska A. and Kalemba D. (2005). Composition of the essential oil of Ocimum sanctum L. grown in Poland during vegetation. J Essent Oil Res; 17: 217–219.

- Khosla M.K. (1995). Sacred tulsi (Ocimum sanctum l.) In traditional medicine and pharmacology. Ancient Science of Life; 15(1) 53-61.

- Kumar P.P., Jyothirmai N., Hymavathi P. and Prasad K. (2013). Screening of ethanolic extract of ocimum tenuiflorum for recovery of atorvastatin induced hepatotoxicity.Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 5, Suppl 4, 346-349.

- Lavanya V. and Kumar S.A. (2011). Study on Ocimum sanctum, Abutilon Indicum and Triumfetta Rhomboidea Plants for its combined Anti-Ulcer Activity.International Journal of Innovative Pharmaceutical Research. 2(1),88-93.

- Maurya (2007).Constituents of Ocimum sanctum with Antistress Activity. J. Nat. Prod, 70, 1410–1416.

- Machado MIL., Silva M.G.V., Matos F.J.A., Craverio A.A. and Alencar W.J. (1999). Volatile constituents from leaves and inflorescence oil of Ocimum tenuiflorum L.f. (syn Ocimum sanctum L) grown in Northeastern Brazil. J Essent Oil Res; 11: 324–326.

- Mahesh S., Gajanan J. and Chintalwar S. C. (2005). Antioxidant and radioprotective properties of an Ocimum sanctum polysaccharide. Redox Report, Vol. 10, No. 5, 257-264.

- Mishra N., Logani A., Shah N., Sood S., Singh S. and Narang I. (2013). Preliminary Ex-vivo and an Animal Model Evaluation of Ocimum sanctum’s Essential Oil Extract for its Antibacterial and Anti- Inflammatory Properties.Oral Health and Dental Management,12(3), 174-179.

- Rajasekharan S., Jawahar C.R., Radhakrishnan K., Kumar P.K.R., and Amma L.S.(1993). Therapeutic potentials of Tulsi : from experience to facts. Drugs News & Views; 1(2): 15–21.

- Helya Rostamkhani, Amir Hossein Faghfouri, Parisa Veisi, Alireza Rahmani, Nooshin Noshadi, Zohreh Ghoreishi. The protective antioxidant activity of ginger extracts (Zingiber Officinale) in acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of animal studies. Journal of Functional Foods, Volume 94, July 2022,

- Arablou, T. & Aryaeian, N. The effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale) as an ancient medicinal plant on improving blood lipids. J. Herb. Med. 12, 11–15 (2018).

- Shahrajabian, M. H., Sun, W. & Cheng, Q. Clinical aspects and health benefits of ginger (Zingiber officinale) in both traditional Chinese medicine and modern industry. Acta Agric. Scand. B 69, 546–556 (2019).

- Brud, W. Handbook of Essential Oils 1029–1040 (CRC Press, 2020).

- Meisy Sitiawani, Zikra Azizah, Ridho Asra, Boy Chandra. Review: Phytochemical of Some Plants with Anticoagulant. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research & Development. Vol 10 (4), 2022.

- Thomas H, Diamond J, Vieco A, Chaudhuri S, Shinnar E, Cromer S, et al. Global Atlas of Cardiovascular Disease 2000-2016: The Path to Prevention and Control. Glob Heart. 2018;13(3):143–63.

- Cohen. Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia: Case Presentation and Review. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4(1):68–72.

- Hirsh J, O’Donnell M, Eikelboom JW. Beyond unfractionated heparin and warfarin: Current and future advances. Vol. 116, Circulation. 2007. p. 552–60.

- Sinurat E, Peranginangin R, Saefudin E. Extractsi lee Uji Aktivitas Fukoilee dari Rumput Laut Coklat (Sargassum crassifolium) sebagai Antikoagulan. J Pascapanen lee Bioteknol Kelaut lee Perikan. 2011;6(2):131–8.

- Ghallab A. In Vitro Test Systems and Their Limitations. EXCLI J. 2013;12(0):1024–6.

- Prasonto D, Riyanti E, Gartika M. Uji Aktivitas Antioksilee Extract Bawang Putih (Allium sativum). Dent J. 2017;4:122–8.

- Untari I. Bawang Putih sebagai Obat Paling Mujarab bagi Kesehatan. GASTER. 2010;7(1):547–54.

- Davison C, Levendal RA, Frost CL. Cardiovascular benefits of an organic extract of Tulbaghia violacea?: Its anticoagulant and anti-platelet properties. 2012;6(33):4815–24.

- Rahmawati R, Fawwas M, Razak R, Islamiati U. Potensi Antikoagulan Sari Bawang Putih (Allium sativum) Menggunakan Metode Lee-White lee Apusan Darah. Maj Farm. 2018;14(1):42.

- Hasanuzzaman M, Ramjan Ali M, Hossain M, Kuri S, Safiqul Islam M. Evaluation of total phenolic content, free radical scavenging activity and phytochemical screening of different extracts of Averrhoa bilimbi (fruits). Int Curr Pharm J. 2013;2(4):92–6.

- Siddique KI, Uddin MMN, Islam MS, Parvin S, Shahriar M. Phytochemical screenings, thrombolytic activity and antimicrobial properties of the bark extracts of Averrhoa bilimbi. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2013 Mar;3(3):94–6.

- Inayah PW. Uji Aktivitas Antiplatelet Antikoagulan lee Trombolisis Ektrak Ethanol Daun Belimbing Wuluh (Averrhoa bilimbiL) InVitro. 2015.

- Lubis ARN. Uji Aktivitas In Vitro Antiplatelet adn Antikoagulan Fraksi N-Heksana Kulit Batang Belimbing Wuluh (Averrhoa bilimbi L.). Skripsi Fak Farm Univ Jember. 2015;1:1–18.

- Oboh G, Odubanjo VO, Bello F, Ademosun AO, Oyeleye SI, Nwanna EE, et al. Aqueous extracts of avocado pear (Persea americana Mill.) leaves and seeds exhibit anti-cholinesterases and antioxileet activities in vitro. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;27(2):131–40.

- Rohmah M, Fickri DZ, Damasari KP. Uji Aktifitas Antikoagulan Extract Alkaloid Total Daun Alpukat (Persea americana Mill) secara In Vitro. JPCAM. 2019;2(2).

- Naqash SY, Nazeer RA. Anticoagulant, antiherpetic and antibacterial activities of sulphated polysaccharide from indian medicinal plant Tridax procumbens L. (Asteraceae). Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;165(3–4):902–12.

- Gupta A, Patil SS, Pendharkar N. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity of aqueous extract of Carica papaya. J Herbmed Pharmacol. 2017;6(4):148–52.

- Parray ZA, Parray SA, Khan JA, Zohaib S, Nikhat S. Anticancer activities of Papaya (Carica papaya): A Review. TANG Humanit Med. 2018;8(4):1–5.

- Maniyar Y, Bhixavatimath P. Antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic activities of aqueous extract of Carica papaya Linn. leaves in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012;3(2):70–4.

- Leeborno AM, Ibrahim SH, Mallo MJ. The Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Effects Of the Aqueous Leaves Extract of Carica Papaya. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2018;13(3):60–3.

- Mandal S De, Lalmawizuala R, Mathipi V, Kumar NS, Lalnunmawii E. An Investigation of the Antioxileet Property of Carica papaya Leaf Extracts from Mizoram, Northeast India. Res Rev J Bot Sci. 2015;4(2):43–6.

- Julianti T, Oufir M, Hamburger M. Quantification of the antiplasmodial alkaloid carpaine in papaya (Carica Papaya) leaves. Planta Med. 2014;80(13):1138–42.

- Vien DTH, Loc T Van. Extraction and Quantification of Carpaine from Carica papaya Leaves of Vietnam. Int J Environ Agric Biotechnol. 2017;2(5):2394–7.

- Rohmah MK, Fickri DZ. Uji Aktivitas Antiplatelet, Antikoagulan, lee Trombolitik Alkaloid Total Daun Pepaya (Carica papaya L.) secara in Vitro. J Sains Farm Klin. 2020;7(2):115.

- Tangkery RAB, Paransa DS, Rumengan A. Test of Anticoagulant Activity to Mangrove Aegiceras corniculatum Extract. J Pesisir lee Laut Trop. 2013;1(1):7–14.

- Aini, Halid I, Ustiawaty J. Skrining Novel Antikoagulan dari Ektraks Mangrove (Rhizophora sp) lee Aktivitasnya sebagai Antikoagulan secara InVitro lee In Vivo. Media Med Lab Sci. 2019;3(2):63–9.

- Chomah I. Uji Efek Antikoagulan Extract Ethanol Kulit Buah Jeruk Purut (Citrus hystrix) pada Mencit Jantan Galur Balb-C. 2010.

- Bandiola T, Corpuz M. Platelet and Leukocyte Increasing Effects of Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels (Myrtaceae) Leaves in a Murine Model. Pharm Anal Acta. 2018;09(05):1–6.

- Rehman AA, Riaz A, Asghar MA, Raza ML, Ahmed S, Khan K. In vivo assessment of anticoagulant and antiplatelet effects of Syzygium cumini leaves extract in rabbits. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):1–8.

- Pawlaczyk I, Czerchawski L, Kuliczkowski W, Karolko B, Pilecki W, Witkiewicz W, et al. Anticoagulant and anti-platelet activity of polyphenolic-polysaccharide preparation isolated from the medicinal plant Erigeron canadensis L. Thromb Res. 2011 Apr;127(4):328–40.

- Lei L, Xue YB, Liu Z, Peng SS, He Y, Zhang Y, et al. Coumarin derivatives from Ainsliaea fragrans and their anticoagulant activity. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–9.

- Warleei IGAAK, Udayani NNW. Pengaruh Pemberian Extract Ethanol Daun Belimbing Wuluh (Averrhoa bilimbi L.) terhadap Waktu Pendarahan lee Koagulasi pad Mencit Jantan (Mus musculus L.). J Ilm Medicam. 2017;3(2):104–9.

- Asare F, Koffuor G, Nyansah W, Gyanfosu L, Abruquah A. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet properties of the latex of unripe fruits of Carica papaya L. (Caricaceae). Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2015;4(6):1183–8.

- Ku SK, Lee IC, Kim JA, Bae JS. Antithrombotic activities of pellitorine in vitro and in vivo. Fitoterapia. 2013;91:1–8.

- Sutopo T. Uji Extract Ethanol 70?un Sirih (Piper betle L.) terhadap Bleeding Time pada Mencit Jantanggalur Swiss Webster. 2016;3(2):10–7.

Shweta Mishra*

Shweta Mishra*

10.5281/zenodo.14887359

10.5281/zenodo.14887359