Abstract

A neurodevelopmental disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) affects around 1 in 54 children globally. No one therapy offers a complete cure because treatment is varied and diverse. The cornerstone of managing ASD has been traditional allopathic methods like behavioural treatments and medication. These have drawbacks, too, such as adverse effects and inconsistent effectiveness, which have sparked interest in alternative approaches like herbal therapy. The effectiveness and safety of both allopathic and herbal therapies for ASD are examined in this review, along with any possible overlaps between them. The aetiology of ASD is complex and includes environmental, neurological, and genetic variables. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, and stimulants are examples of allopathic medicines that target symptoms but frequently have negative side effects. Herbal remedies such as Ashwagandha, Bacopa monnieri, and Ginkgo biloba are thought to have neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. However, more research through clinical studies is needed to understand their safety and effectiveness fully. The review compares and contrasts herbal and allopathic remedies, emphasising the advantages and disadvantages of each. Current trends, research gaps, and ethical issues are also covered, especially as they relate to the use of herbal remedies in paediatric populations.

Keywords

Biochemical imbalances, Autism, impaired communication, case report findings, complementary medicines for ASD

Introduction

A neurodevelopmental disorder known as ASD is marked by difficulties with social interaction, communication, and limited behaviours. Since ASD is a spectrum condition, there is a wide range of symptoms and degrees of impairment in those who have it. ASD includes a variety of disorders that share basic traits, including trouble with language, creativity, socialising, and repressive behaviours[1]. It impacts all aspects of child development, needing examination of social skills, mobility, language, daily living skills, play, executive functions, and recognition of social and academic skills. The term "spectrum" refers to the different symptoms and support levels of ASD, which is vital for delivering individualised interventions and support to individuals and their families. Hans Asperger's observations and Leo Kanner's 1943 study shed light on the range of ASD presentations, from intense withdrawal to exceptionally high intellectual ability. Asperger's identification of differing intellectual capacities and Kanner's depiction of intense seclusion and regular adherence resulted in the diagnosis of ASD[2]. People with various talents and difficulties, from nonverbal to extraordinary capabilities, are included in this disease[3]. The intricacy of ASD and its concomitant conditions, which include melancholy, anxiety, ADHD, and epilepsy, highlight the necessity of thorough evaluation and assistance. Diagnoses for ASD encompass variances in sensory experiences, learning styles, repetitive motions, and challenges with both verbal and nonverbal.

communication[4].Geographical location and racial/ethnic groupings have an impact on the frequency of ASD, which was predicted to be 14.7 per 1000 children in 2010 and 2012 and 16.8 per 1000 in 2014. A comprehensive review and meta-analyses of 54 research found that the male-to-female ratio of 4.2 indicates that the prevalence is four times higher in boys than in girls. To provide individualised therapies and support to people with ASD and their families, it is important to comprehend this heterogeneity[5].

Challenges associated with the management of autism:

The treatment of ASD is complicated because of the disorder’s distinct symptoms, co-occurring illnesses, and communication difficulties. Since every person with ASD has a different collection of features, therapies must be customised for each individual. Anxiety, ADHD, sensory processing disorders, and epilepsy are examples of co-occurring illnesses that might complicate treatment plans and call for extra medical care[6],[7].Another difficulty is interaction since many people with ASD find it difficult to communicate their needs or read social signs. This makes it challenging for caregivers and medical professionals to interact with these people in a meaningful way[8]. For non-verbal people, alternative communication techniques like picture exchange systems or speech-generating gadgets could be required; they require specific training and resources[9].The problem of diverse individual requirements, co-occurring disorders, and behavioural issues is part of managing ASD, sometimes in underfunded settings. Repetitive behaviours, strict routines, and transitional obstacles are common behavioural issues that frequently call for Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) therapy. However, due to high prices and a lack of qualified specialists, access to these therapies may be restricted, especially in rural or disadvantaged areas. This problem is made worse by lengthy waitlists for diagnosis and treatment. The sensory sensitivity associated with ASD can lead to discomfort or meltdowns, requiring environmental changes[10].

Current existing knowledge of the

environmental, neurological, and genetic

components of ASD:

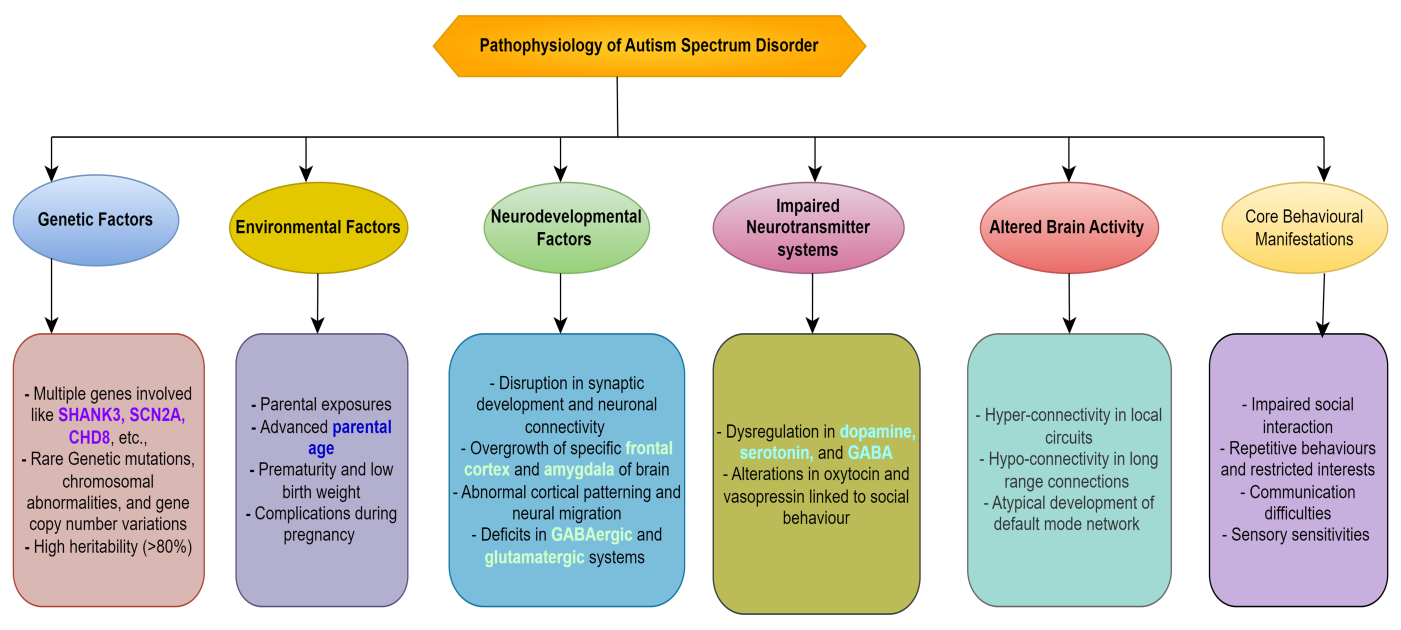

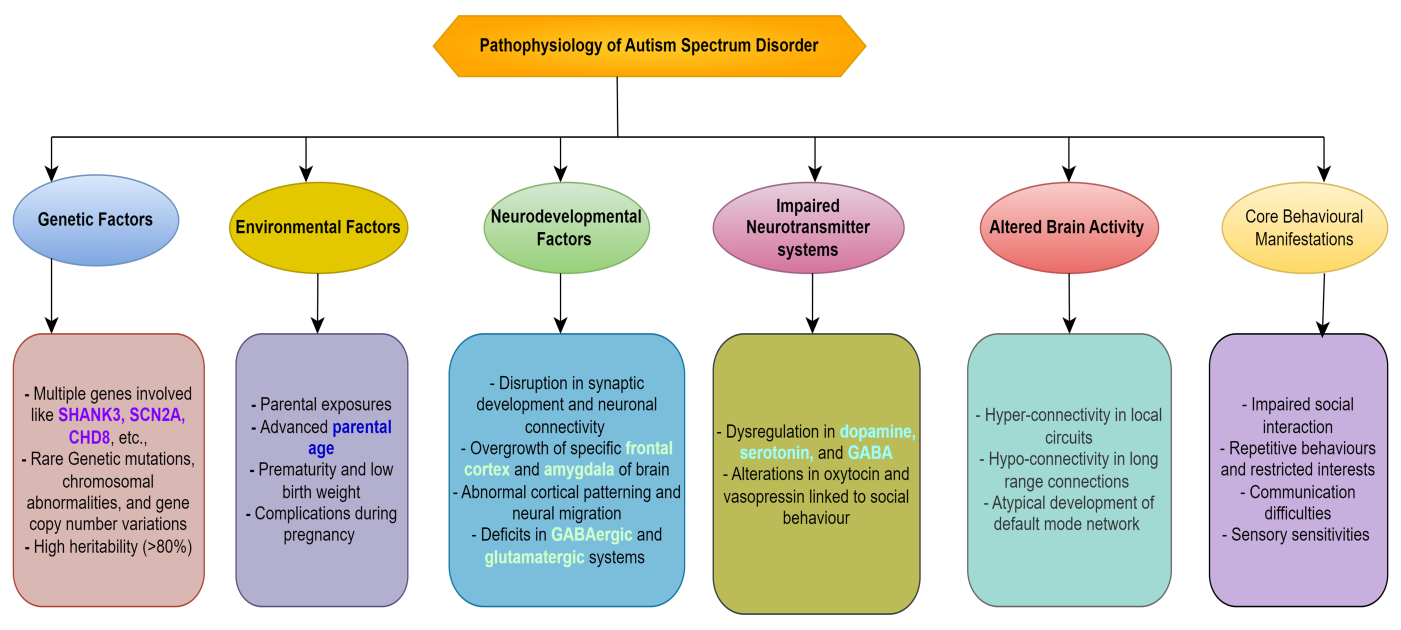

1. Genetic factor:

A genetic illness, ASD affects 40–80% of the risk and is caused by many genes that work in distinct ways. ASD is associated with common variations, both inherited and de novo mutations, which frequently occur in genes essential for brain development. De novo mutations happen independently when reproductive cells arise or an embryo develops. Certain genetic aberrations can cause autism, and rare genetic diseases such as Rett syndrome, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, and Fragile X syndrome provide light on this process. Gene-environment interactions imply that in those with a genetic predisposition, environmental variables, including prenatal exposures, may cause ASD.

2. Neurological factor:

ASD is a neurological disorder with a high hereditary component, estimated to be between 50 and 90 percent. ASD has been associated with mutations in several genes, including uncommon ones related to synaptic function, and copy number variations (CNVs). Anomalies related to early overgrowth, altered cortical thickness, neuroinflammation, brain structure and function, and synaptic connection all have an impact on brain development. Unusual alterations in cortical thickness have been seen in certain ASD patients, which may be related to variations in brain circuitry. ASD may potentially be influenced by immunological system malfunction and neuroinflammation. Certain individuals diagnosed with ASD may also have hyperactive microglia, which are the brain's immune cells.

3. Environmental factor:

Maternal infections, elevated levels of stress during pregnancy, advanced ages of the mother and father, and vitamin deficiencies are prenatal variables linked to ASD. The risk of ASD can also be raised by preterm delivery, difficult deliveries, and early childhood exposure to environmental pollutants. The gut microbiome is one of the postnatal environmental factors that can affect behaviour and neurological development through immunological pathways, inflammation, and metabolite synthesis. Certain behaviours associated with ASD might also be made worse by the sensory environment, which can be overpowering or less present during the early critical stages. These elements are not usually causative, though.

ASD is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormal brain development due to altered epigenetic regulation. This is influenced by environmental factors like diet, toxins, and stress. ASD is believed to arise from a combination of genetic vulnerability and environmental triggers, with individuals with genetic predispositions being more sensitive. Genetic abnormalities are the main cause of ASD, a complicated illness that is impacted by both environmental and genetic factors. It needs the integration of environmental science, neurology, and genetics to fully comprehend this condition[11].

Biochemical imbalances in ASD:

ASD is characterized by various biochemical abnormalities, including neurotransmitter imbalances, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

1. Neurotransmitter imbalances:

These imbalances contribute to neural dysfunction and behavioural traits in individuals with ASD. Serotonin, a key neurotransmitter, is elevated in 25-30% of ASD patients, possibly due to abnormal metabolism or transport. GABA, the main inhibitory neurotransmitter, is impaired in ASD, leading to an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neural circuits. This imbalance can lead to sensory overload, anxiety, and repetitive behaviours. Glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, is over-activated in certain brain regions, leading to excitotoxicity. Dopamine, involved in reward processing and motivation, is also affected in ASD. The mesolimbic dopamine pathway may function differently in ASD, potentially reducing motivation for social interaction. Acetylcholine, crucial for learning, memory, and attention, is also affected in ASD patients.

2. Oxidative stress:

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction by the body can lead to oxidative stress, which can harm molecules and cells, particularly in delicate organs like the brain. Individuals with ASD often exhibit elevated ROS levels, reduced antioxidant defences, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired brain development, which can impair synapse formation, neural connectivity, and plasticity, which are crucial for normal cognitive and social development.

3. Inflammation and Immune dysregulation:

ASD development and persistence may be influenced by immune system malfunction and chronic inflammation. This encompasses hyper activated microglia, increased pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, modified immune cell function, stimulation of the mother's immune system, and autoimmune processes. These elements may interfere with neural signalling, exacerbate behaviours linked to autism spectrum disorders, and jeopardise the blood-brain barrier's integrity. Additionally, prenatal exposure to maternal immunological activation, such as infections or autoimmune disorders, has been related to an increased risk of ASD.

4. Metabolomic abnormalities:

Metabolic anomalies, such as altered amino acid metabolism, elevated homocysteine levels, and disordered one-carbon metabolism, are observed in individuals diagnosed with ASD. These anomalies may impact gene expression and brain function by causing oxidative stress, imbalances in neurotransmitter balance, neurodevelopmental problems, and altered epigenetic control.

ASD is characterized by biochemical abnormalities involving disruptions in neurotransmitter systems, redox balance, and immune function, leading to neurodevelopmental challenges like social communication, repetitive behaviours, and sensory sensitivities. However, understanding these pathways' interactions and variations among individuals on the autism spectrum remains a challenge[12]

Figure 1. Illustrates how a confluence of environmental, genetic, and neurological variables leads to the development of ASD.

Allopathic drugs used for the treatment of ASD:

ASD is one of the medical diseases that are diagnosed, treated, and managed by allopathic medicine, also referred to as conventional or Western medicine. It targets certain symptoms and co-occurring disorders that people with ASD face. Even though ASD cannot be cured, some drugs can enhance functioning and well-being by addressing particular issues. Doctors frequently prescribe medication to treat behavioural problems, mental disorders, and other diseases that can coexist with ASD. Medication has been demonstrated to be both safe and helpful in lowering symptoms such as aggressiveness, hyperactivity, and anxiety in children with ASD. However, a skilled healthcare provider should prescribe and oversee the use of these drugs, and they should be a part of an all-encompassing treatment strategy. There are some medications commonly used to address specific symptoms or conditions in adults with autism (Table 1).

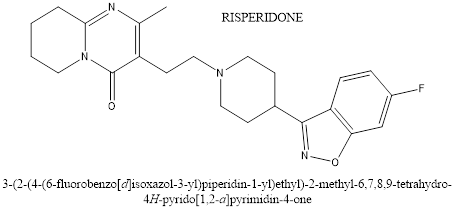

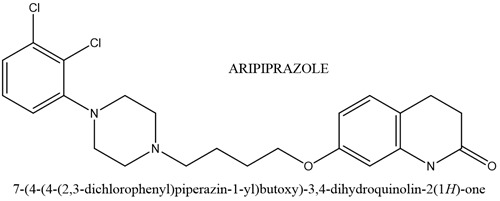

- Antipsychotics:

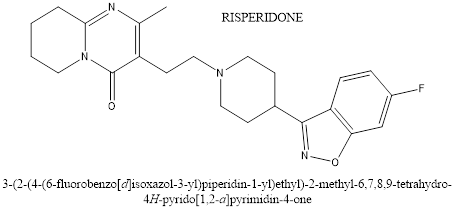

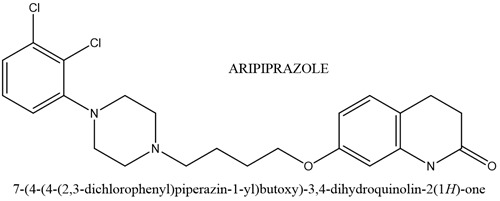

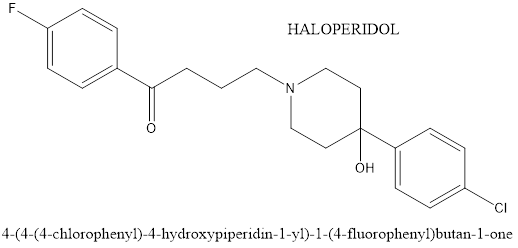

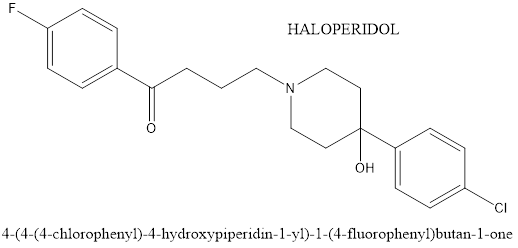

These drugs are administered to treat symptoms like hostility, impatience, and compulsive conduct. Antipsychotics work by modifying the brain’s dopamine and serotonin levels, which in turn helps to control mood and behaviour. To reduce challenging behaviours including irritability, aggressiveness, and self-injurious conduct, antipsychotics like risperidone, aripiprazole, and haloperidol work primarily on the dopamine and serotonin systems[13].

Risperidone is a potent serotonin receptor blocker with additional dopamine-blocking properties. It blocks the postsynaptic dopamine receptors in the basal ganglia, hypothalamus, limbic system, brain stem and medulla. Risperidone has a blocking effect on dopaminergic D2 receptors and 5-hydroxy tryptamine. Which is approved by the FDA for treating irritability in children with ASD ages 5 to 16 years. It can help to reduce aggression, deliberate self-harm and temper tantrums.Aripiprazole is efficacious for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism.it is an atypical antipsychotic used in the treatment of a wide variety of mood and psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar, major depressive disorder, irritability associated with autism, and Tourette’s syndrome. The mechanism of action of aripiprazole is not yet fully understood, but it is known that these drugs generally bind to dopaminergic receptors in the brain, modulation the action of dopamine, although such therapies are promising, more effective drugs in combat of symptoms such as anxiety and irritability are lacking as well as reducing symptoms in a boarded way without pronounced side effects.

Only young patients under the supervision of a child psychiatrist (age 18) should be administered haloperidol. It has been observed that the Haldol medication, the brand name Haldol, reduces hyperactivity, impatience, and violence. The side effects include constipation, insomnia, drowsiness, and upper respiratory tract infection. Mechanism of action involves blocking dopamine receptors in the brain, which helps to regulate mood, behaviour and emotions. By doing so, haloperidol can help to reduce symptoms such as aggression and hesitation in individuals with ASD[14].

- Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI):

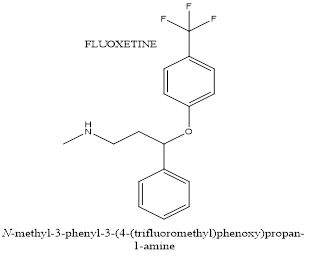

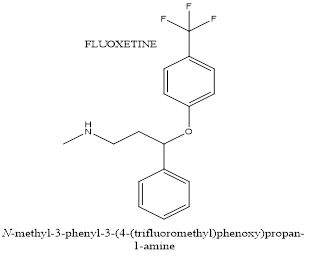

SSRIs such as fluoxetine and citalopram act primarily on the serotonin system and are used in the treatment of ASD for repetitive and challenging behaviour.A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) called Fluoxetine is occasionally used to treat ASD. It focuses on the anxiety, mood swings, and repetitive behaviours typical of ASD individuals. It improves mood control and lowers anxiety by raising serotonin levels in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting serotonin reuptake. In individuals with ASD, this may lessen recurrent behaviours, anxiety, and mood disorders. However, due to possible adverse effects including gastrointestinal problems and sleep disruptions, medication must be continuously monitored and its efficiency is not always consistent. For fundamental ASD symptoms including social communication impairments, fluoxetine is ineffective.

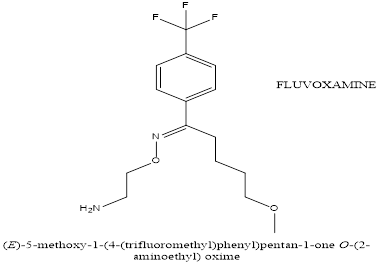

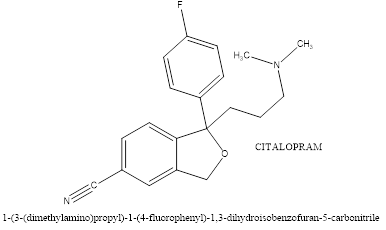

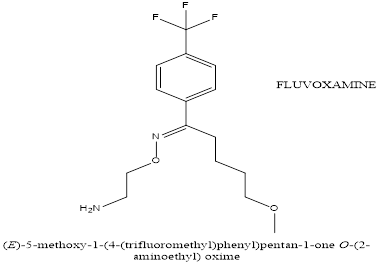

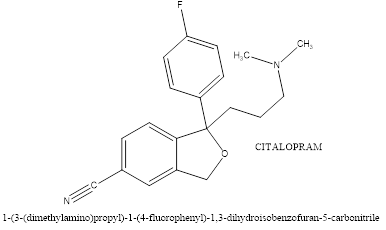

Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is used to treat symptoms in individuals with ASD, particularly for managing repetitive behaviours, anxiety, and irritability. It works by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin, a key neurotransmitter involved in mood, anxiety, and repetitive behaviours. This increases serotonin availability, which helps regulate emotional and behavioural responses. Fluvoxamine may also reduce repetitive behaviours, such as stereotypies, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, which are common in ASD. Its effect on serotonin transmission may alleviate anxiety symptoms, improve daily functioning, and reduce irritability and aggression. Fluvoxamine may also have anti-inflammatory properties, modulating the sigma-1 receptor, which can reduce neuroinflammation, contributing to ASD symptoms. However, its efficacy varies and side effects like nausea, sleep disturbances, agitation, and behavioral activation may occur.Anxiety, irritability, repetitive behaviours, and mood disorders are some of the symptoms of ASD that can be treated with citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). As a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, anxiety, and behaviour, serotonin's reuptake is inhibited by it. As these symptoms can be more prominent in people with ASD, citalopram may be able to aid with anxiety, mood stabilisation, and repetitive behaviours. For people who struggle with depression or mood swings, in particular, it also aids in mood stabilisation. More steady behaviour and less emotional volatility can result from its capacity to lessen emotional liability and hostility.

While citalopram is not frequently used as a first-line treatment for fundamental symptoms of ASD, such as difficulty with social communication, it may be useful in treating related symptoms including anxiety, irritability, and repetitive behaviours. Its usefulness in decreasing repetitive behaviours in kids with ASD has varied, nevertheless, with inconsistent findings[15].

- Psychostimulants:

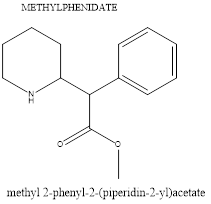

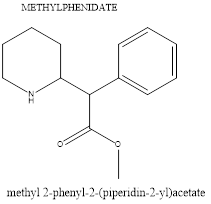

Psychostimulants, such as Ritalin and Adderall, are commonly used to treat ADHD and can also be used to control symptoms in individuals with ASD. They help manage impulsivity, hyperactivity, and inattention in ASD by increasing dopamine and norepinephrine availability in specific brain areas. This reduces impulsive behaviour, improves focus, and enhances executive functioning. Psychostimulants also improve self-regulation and task completion by focusing on the frontal lobes. They help manage co-occurring symptoms of ASD, such as inattention and hyperactivity, improve executive function, reduce irritability, and enhance engagement in therapy or learning. Examples of Psychostimulants include methylphenidate and amphetamines, which raise norepinephrine and dopamine levels, enhancing executive functioning, attention span, and behavioural control. Although they don't address the main symptoms of ASD, they can reduce disruptive behaviours and increase treatment and learning involvement.

- ?2 agonist:

Clonidine and guanfacine are examples of ?2-adrenergic agonists that are used to treat symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and ASD. These drugs target the brain's ?2A receptors, which control norepinephrine activity, which is part of the adrenergic system. They function by preventing the release of norepinephrine, lowering impulsivity and hyperactivity, and modifying behavioural and emotional control. Additionally, they contain sedative and anxiolytic properties that lower aggressiveness, anxiety, and general alertness. They can be especially helpful for people who have trouble falling or staying asleep in managing anxiety and sleep disruptions. The anxiolytic effects can assist control of generalized anxiety and social anxiety, which can worsen other symptoms in ASD. Nevertheless, basic symptoms of ASD such as difficulty with social communication or repetitive behaviours cannot be treated with ?2 agonists. They don't deal with the main signs and symptoms of ASD, such as trouble with social interactions, repetitive behaviours, and communication impairments. Additionally, their reactions vary; some people may see notable behavioural changes, while others might not. Bradycardia, low blood pressure, drowsiness, and dizziness are typical side effects. It is advisable to go off ?2 agonists gradually while under medical care to prevent rebound hypertension or exacerbation of symptoms. Monitoring closely is necessary to control any possible adverse effects. In general, ?2-adrenergic agonists are useful in treating ASD symptoms such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, aggressiveness, and irritability[16].

- Other medicines:

Other prescription medications, such as anxiolytics (benzodiazepines) or mood stabilisers (ditum, valproate), may occasionally be prescribed to treat particular conditions or symptoms in adults with autism; however, because of the possibility of interactions and side effects, these drugs are usually taken with caution[17].

Figure 2. Chemical structure of Risperidon

Figure 3. Chemical structure of Aripiprazole

Figure 4. Chemical structure of Haloperidol

Figure 5. Chemical structure of Fluvoxamine

Figure 6. Chemical structur of Fluoxetine

Figure 7. Chemical structure of Citalopram

Figure 8. Chemical structure of Methylphenidate

Table 1. Medications used for treating autism

|

Chemical name

|

Marketed products

|

Chemical formula

|

Preferred age in years

|

Receptors responsible for treating autism

|

|

Antipsychotics

|

|

1. Risperidone

|

Risperdal

|

C23H27FN4O2

|

5 - 6

|

Dopaminergic D2receptors and 5-hydroxy tryptamine

|

|

2. Aripiprazole

|

Abilify, Aripiprex

|

C23H27Cl2N3O2

|

6

|

Dopaminergic receptors

|

|

3. Haloperidol

|

Haldol

|

C21H23ClFNO2

|

Under 18

|

Dopamine receptors

|

|

1. Fluoxetine

|

Prozac, Lovan

|

C17H18F3NO

|

8 TO 18

|

5HT2C

Receptors

|

|

2. Fluvoxamine

|

Faverin, Floxyfral,

|

C15H21F3N202

|

Above 18

|

5HT1C

Receptors

|

|

3. Citalopram

|

Celapram, Celica

|

C20H21FN2O

|

Above 18

|

5HT

Receptors

|

|

1. Methylphenidate

|

Concerta, Ritalin, Gen Rx

|

C14H19N02

|

6 to 18

|

Dopamine and nor-epinephrine

Dopamine and nor-epinephrine

|

|

1. Clonidine

|

Catapres, Kapvay

|

C9H9Cl2N3

|

Above 6

|

?2 receptors

|

|

2. Melatonin

|

Natrol melatonin.

|

C13H16N2O2

|

Above 3

|

Melatonin receptors

|

Herbal drugs used for ASD treatment:

Anxiety, hyperactivity, and cognitive difficulties are just a few of the symptoms of ASD that herbs may help with by supporting brain function[18]. Certain herbs have neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and relaxing qualities that may help people with ASD, but they shouldn't be used in place of traditional therapies. Among the plants that are frequently researched are Centella asiatica, St John Wort[19,20], Ginkgo biloba, Bacopa monnieri, and Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha). These herbs provide supplementary methods for managing the symptoms of ASD by modifying neurotransmitter activity, lowering oxidative stress, and enhancing synaptic plasticity[18,21–24].Ginkgo biloba, a medicinal herb, has been investigated for potential benefits in alleviating symptoms of ASD. Its neuroprotective and antioxidant effects include reducing oxidative stress, which contributes to inflammation and neuronal damage. Ginkgo biloba also improves cognitive functions by improving cerebral blood flow and modulating neurotransmitter systems. It may also reduce hyperactivity and behavioural issues in individuals with ASD. It has also been combined with other treatments, such as risperidone. However, there is mixed evidence and side effects, and it is important to consult a healthcare provider before using Ginkgo biloba in a treatment plan[25–27].Bacopa monnieri, also known as Brahmi, is an herb used in Ayurvedic medicine for cognitive enhancement and neurological health. It has been studied for its potential to improve symptoms associated with ASD. Bacopa monnieri ionotropic effects improve memory and cognitive function, which are common in individuals with ASD. Its anxiolytic properties reduce anxiety and stress by modulating neurotransmitter levels, which may help those experiencing heightened levels of anxiety, social stress, and sensory overload. Bacopa is rich in antioxidants, which protect the brain from oxidative stress and inflammation, which can contribute to neurological and behavioural challenges. It supports neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, which are crucial in neurodevelopmental disorders like ASD. Bacopa may also help reduce symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and attention difficulties, which are common in children with ASD. It also supports the gut-brain axis, which is connected to neurodevelopment. However, Bacopa monnieri has limitations, including limited human studies, potential side effects, and dose-dependent effects[28].Ashwagandha, also known as Withania somnifera, is an adaptogenic herb used in Ayurvedic medicine for its stress-relieving and neuroprotective properties. It has been shown to improve symptoms associated with ASD by reducing stress, anxiety, and enhancing cognitive function. Ashwagandha's adaptogenic effect helps manage stress, reducing anxiety-related behaviours and promoting relaxation. It also supports cognitive function, particularly memory, learning, and focus, by promoting neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity. It may also reduce hyperactivity and behavioural problems, balancing neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin. Ashwagandha's antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties protect against oxidative stress, which can lead to inflammation and neuronal damage in ASD. Its immunomodulatory effects help balance immune function, potentially reducing neuroinflammation and improving brain function and behaviour in ASD patients. It also improves sleep quality, promoting relaxation and better mood regulation. It may also support emotional regulation by modulating neurotransmitters. However, there is limited direct clinical research on Ashwagandha's effects on ASD, side effects, and individual responses. Therefore, more targeted research is needed to confirm its effectiveness in individuals with ASD and should be used under the guidance of a healthcare provider[29].The potential advantages of using several herbs to treat the symptoms of ASD have been studied and a few of them are also mentioned in Table 2. The antioxidant-rich herb Centella asiatica is thought to improve mental clarity and lessen anxiety. By lowering oxidative stress and blocking pro-inflammatory cytokines, the turmeric-rich herb Curcuma longa possesses anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties[30]. Lemon balm Melissa officinalis acts on GABA receptors to provide relaxing and anxiolytic effects[31]. It has been demonstrated that the green tea Camellia sinensis[32], which contains EGCG, controls synaptic plasticity, prevents oxidative damage, and alters signalling pathways linked to the pathophysiology of ASD[33]

Table 2. Herbal medicines used to treat ASD

|

Scientific name of the plant

|

Common name

|

Availability

|

Active compounds

|

Therapeutic effect

|

Mechanism of action

|

Reference

|

|

Zingiber officinale

|

Ginger

|

Widely available as fresh root, dried powder, extracts, capsules, and oils

|

Gingerols, Shogaols, Zingerone, Essential oils

|

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, gastrointestinal support

|

Reduces inflammation, modulates neurotransmitters, antioxidant activity, supports digestion

|

[34,35]

|

|

Acorus calamus

|

Sweet Flag, Calamus, Vacha, Bach

|

Widely available in parts of Asia, North America, and Europe. Found in wetlands and often used in traditional medicine.

|

?-Asarone

?-Asarone

Eugenol

Calamenone

Sesquiterpenes

Acoradin

|

-Neuroprotective

Antimicrobial (fights infections)

- Antispasmodic (reduces muscle spasms)

- Anti-inflammatory (alleviates inflammation)

- Digestive aid (used for gastrointestinal disorders)

- Sedative (induces calmness)

|

-In the brain, ?-asarone increases acetylcholine, decreases acetylcholinesterase, and modifies cholinergic activity to improve memory and cognition.

-prevents the production of microbial cell membranes and interferes with biological functions.

-prevents the synthesis of mediators such as prostaglandins and inflammatory cytokines.

-serves as a carminative to ease stomach pain and flatulence by stimulating digestive enzymes.

|

[36,37]

|

|

Actea racemosa

|

American Wormwood

|

Available as dried herb, extracts, and essential oils in herbal shops and online

|

Essential oils (thujone), Flavonoids, Sesquiterpenes

|

-Digestive aid, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial

|

Modulates neurotransmitter activity, reduces inflammation, supports digestive health

|

[38,39]

|

|

Lobelia inflata

|

Indian tobacco or emetic weed

|

Widely available in North America, Asia, Europe (as extracts, tinctures and capsules)

|

Lobeline, Lobelanine, isolobelanine

|

Respiratory support, anti-inflammatory, relaxant

|

Modulates dopamine levels, stimulates neurotransmitter release, reduces spastic movements, potential cholinergic and dopaminergic effects

|

[40,41]

|

|

Paeonia lactiflora

|

White Peony

|

Widely available in Asia, Europe, and North America (herbal extracts and capsules)

|

Paeoniflorin, Tannins, Flavonoids, Terpenoids

|

Anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, mood stabilizer

|

Modulates GABAergic activity, reduces neuroinflammation, antioxidant effects

|

[42,43]

|

|

Piper nigrum

|

Black Pepper

|

Widely available worldwide

|

Piperine, Volatile oils (e.g., Sabinene, Limonene), Alkaloids

|

Anti-inflammatory, enhances bioavailability, neuroprotective

|

Increases serotonin and dopamine, enhances nutrient absorption, reduces oxidative stress

|

[44,45]

|

|

Glycine max

|

Soybean

|

Widely available as whole beans, tofu, soy milk, and supplements

|

Isoflavones (e.g., genistein, daidzein), Glycine, Phytosterols

|

Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, cognitive enhancer

|

Modulates neurotransmitter activity, reduces oxidative stress, anti-inflammatory

|

[46–48]

|

|

Cannabis sativa

|

Cannabis, Marijuana

|

Available in various forms (dried flower, oils, edibles, tinctures) in regions where legal; requires prescription in some areas

|

THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol), CBD (Cannabidiol), CBG (Cannabigerol), Terpenes

|

Reduces anxiety, improves mood, alleviates sensory overload, enhances social interaction

|

Modulates the endocannabinoid system, reduces inflammation, alters neurotransmitter release

|

[49,50]

|

|

Astragalus propinquus

|

Astragalus, Huang Qi

|

Widely available in health food stores and as supplements in various forms (powder, extract, capsules)

|

Astragalosides, Flavonoids, Polysaccharides

|

Immune support, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, antioxidant

|

Modulates immune response, reduces inflammation, supports neurogenesis

|

[51,52]

|

|

Salvia officinalis

|

Sage

|

Widely available as dried leaves, essential oil, extracts, and capsules

|

Rosmarinic acid, Thujone, Carnosic acid, Flavonoids

|

Cognitive enhancement, anxiety reduction, anti-inflammatory

|

Antioxidant properties, modulation of neurotransmitter activity, anti-inflammatory effects

|

[53,54]

|

|

Lepidium sativum

|

Garden Cress

|

Widely available as seeds and fresh leaves in grocery stores and health food shops

|

Glucosinolates, Vitamins (A, C, K), Antioxidants, Omega-3 fatty acids

|

Nutritional support, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant

|

Modulates antioxidant defenses, supports cognitive function, anti-inflammatory effects

|

[55,56]

|

|

Passiflora incarnata

|

Passionflower

|

Widely available as dried herb, teas, extracts, and capsules in health food stores and online

|

Flavonoids (e.g., chrysin), Harman alkaloids, Caffeic acid

|

Anxiety reduction, sedative, sleep aid

|

Modulates GABA receptors, increases serotonin levels, reduces anxiety

|

[57,58]

|

|

Moringa oleifera

|

Moringa, Drumstick tree

|

Widely available as fresh leaves, powder, capsules, and oils in health food stores and online

|

Vitamins (A, C, E), Minerals (Calcium, Iron), Antioxidants (Quercetin, Chlorogenic acid), Amino acids

|

Nutritional support, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective

|

Modulates inflammation, reduces oxidative stress, supports cognitive function

|

[59,60]

|

Comparative Analysis of Allopathic and Herbal Treatments

Allopathic medicine, also referred to as Western medicine, targets certain symptoms or illnesses with scientifically proven therapies including medications and surgeries. It places a strong emphasis on evidence-based procedures, which enable accurate dosage and predictable results. Nevertheless, it may ignore holistic health factors and result in adverse consequences from synthetic drugs[61].Plant-based compounds are used therapeutically in herbal medicine, which is a component of traditional systems like Ayurveda or TCM. Its intricate constituents include anti-inflammatory and antioxidant qualities, among other possible health advantages[62]. Challenges include individual reactions, product variations, and possible drug interactions. Despite considerable scientific backing, practitioners need to be cautious since certain therapies lack solid proof[63].The safety profiles of allopathic and herbal remedies differ, with allopathic medications potentially causing mild to severe adverse effects. Because of their natural origins, herbal treatments are thought to be safer; nonetheless, variances in strength and efficacy may result from a lack of standardisation in manufacturing[64]. Some plants, such as St. John's wort, have the potential to adversely interact with allopathic drugs. St. John's wort, for instance, may conflict with antidepressants and anticoagulants[65].Health authorities oversee allopathic therapies to ensure they satisfy safety and efficacy criteria, while herbal medications are not as strictly regulated, which results in variations in their efficacy and quality. Even though many nations are enacting stronger rules, customers may become confused due to the absence of widely recognised standards[66].

Herbal and allopathic medicine are both beneficial modalities, each with advantages and disadvantages. Herbal therapy prioritises health and prevention, whereas allopathic treatment is precise and evidence-based67. Both are used in an integrated strategy that addresses larger health concerns with herbal medicines and allopathic procedures where appropriate. This method acknowledges that the synergy of many treatment methods is frequently necessary for optimal healthcare, enabling complete and individualised patient care[67].

The Potential for Combining Allopathic and Herbal Treatments to Enhance Therapeutic Outcomes

Complementary or integrative medicine, which combines allopathic and herbal therapies, is a viable way to enhance patient results. This holistic approach integrates the best features of both systems to maximise therapeutic efficacy, reduce side effects, and address a broader spectrum of health conditions14.

1. Enhanced Efficacy through Synergy

Integrating alternative and herbal remedies can increase the efficacy of prescription drugs. For example, curcumin enhances the anti-inflammatory properties of NSAIDs. Herbal remedies can also lessen the negative effects of allopathic drugs; for example, ginger can help with chemotherapy nausea. It is a promising method for treating a variety of illnesses because of the potential for better patient outcomes and more adherence to treatment plans due to its synergistic impact[68].

2. Comprehensive Symptom Management

Herbal medicine treats the whole person, taking into account not just the illness but also its symptoms and general health. It provides all-encompassing symptom management, enabling medical professionals to give long-term pain management, inflammation reduction, and instant relief for chronic pain. In contrast to allopathic therapies that target individual illnesses, this combination can result in better overall health results and an enhanced quality of life[69].

3. Individualized Treatment Plans

Integrative medicine develops individualised treatment strategies by combining herbal and allopathic therapies. This method enables medical professionals to customise therapies according to each patient's condition, preferences, and lifestyle while also acknowledging their health requirements. For example, a patient with anxiety may benefit from herbal therapies in addition to prescribed drugs. By encouraging a sense of agency and empowerment, this patient-centred approach increases the patients' involvement in the healing process[70].

4. Safety and Reduced Side Effects

Although allopathic drugs might be helpful, they frequently have negative side effects that can make it difficult for patients to take them as prescribed. Alternatives with less adverse effects can be obtained by including herbal remedies, such as liquorice root or probiotics. To protect patient safety, healthcare professionals must carefully assess potential interactions and modify treatment plans since certain herbal medicines might interact with allopathic pharmaceuticals[71].

5. Emphasizing Prevention and Wellness

Herbal remedies support health and stave off illness, which is consistent with the focus on preventative care in allopathic medicine. Reducing chronic disease occurrence, including immune-boosting treatments like Echinacea or elderberry can supplement immunisations and preventative measures, improving health outcomes and lowering healthcare expenditures.

The creation of individualised, all-encompassing treatments through the fusion of herbal and allopathic therapies might enhance therapeutic results. However, obstacles include the necessity for more study and the standardisation of herbal goods. A move towards a more holistic approach that values both contemporary scientific discoveries and conventional knowledge is reflected in the rising interest in integrative medicine, which will eventually benefit patients and enhance their quality of life[72].

Case studies that have investigated the use of combination therapies for ASD:

A complicated neurodevelopmental disorder, ASD calls for a variety of therapy modalities. The possible advantages of combination treatments, which incorporate many treatment methods, are the subject of a recent study. Although there isn't a single medication that works for everyone, combination treatments are showing promise in the management of ASD.

- The findings of the case study conducted by Scahill Lawrence et al. (2022), aimed to compare Direct Instruction Language for Learning (DI) plus treatment as usual (TAU) to TAU alone in children with autism spectrum disorder and moderate language delay. Eighty-three children (4-7 years 11 months) were randomly assigned to DI + TAU or TAU alone for 6 months. Trained therapists delivered DI in twice weekly, 90-minute sessions for 24 weeks. The primary outcome was the standard score on the age-appropriate Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF) version. The key secondary measure was the proportion of children rated as Much Improved or Very Much Improved on the Clinical Global Impression Improvement (CGI-I) scale. The study found that DI+TAU did not meet the pre-specified difference from TAU on the CELF, but when adjusted for IQ, DI+TAU was superior to TAU on the CELF at the endpoint and DI+TAU was superior to TAU on the CGI-I[73].

- In a case study conducted by Scahill L et al. (2012), the researchers explored the impact of the combination of risperidone medicine and parent education. 124 kids with ASD and severe behavioural issues, ages 4-13, were split up into groups for this experiment and given either risperidone by itself or risperidone in combination with parent education. 124 children with severe behavioural issues and Pervasive Developmental Disorders were randomly assigned to receive either medication alone (MED; risperidone 0.5 to 3.5 mg/day) or medication plus parental involvement (COMB) in a 24-week research study. According to the study, both groups improved in every Vineland domain over the 24 weeks. Vineland Socialisation and Adaptive Composite Standard scores improved more in the COMB group than in the MED group. The Socialisation and Communication domains improved more in COMB than in MED on Age Equivalent scores. Compared to MED, children in the COMB group had a twofold higher chance of improving their Vineland Communication Age Equivalent score by at least six months. Reducing severe maladaptive behaviour encourages adaptive behaviour to improve, according to the study's findings, and medicine with parent education offers a little boost compared to medication alone[74].

- As per the key findings of a controlled trial conducted by Bent S. et al. (2011), in their pilot randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of omega-3 fatty acids on hyperactivity in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Over 12 weeks, 27 children aged 3-8 were given either omega-3 supplements or a placebo. Although the study did not find a statistically significant reduction in hyperactivity, the omega-3 group showed a slight improvement compared to the placebo group. The treatment was well-tolerated, and the study suggested that while omega-3 fatty acids may have a small beneficial effect, larger trials are needed to confirm these findings. The study also noted correlations between changes in specific fatty acid levels and hyperactivity. Despite the lack of significant results, the potential for omega-3 fatty acids as a treatment for hyperactivity in ASD remains an area for further research[75].

- The randomized clinical trial report by Aman M G et al. (2017), investigates the safety and efficacy of memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, in children with autism. The study consisted of a 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial followed by a 48-week open-label extension. A total of 121 children were involved, with memantine doses ranging from 3 to 15 mg/day. Results showed no significant difference in social responsiveness between the memantine and placebo groups after 12 weeks. Both groups showed some improvement, but no efficacy was demonstrated in treating core symptoms of autism. The treatment was generally well-tolerated, with no significant adverse effects. The study highlights the need for further trials to assess memantine’s potential for treating other conditions in children[76].

- The randomized controlled trial by Granpeesheh D et al. (2010), presents a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial examining the efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for children with autism. The study involved 34 participants who completed 80 sessions of either HBOT or a placebo treatment. The results showed no significant differences between the HBOT and placebo groups in any of the measured outcomes, including social communication, repetitive behaviors, and adaptive functioning. Both groups demonstrated some improvement over time, but the study concluded that HBOT, at the tested dose of 24% oxygen at 1.3 atmospheric pressure, does not provide a therapeutic benefit for autism symptoms. The findings reinforce previous studies that also failed to show a significant effect of HBOT on autism symptoms, and the authors recommend against its use as a treatment for autism[77].

- The case report by Fingert S B et al. (2017), discusses the findings of a randomized clinical trial (RCT) that evaluated the effects of improvisational music therapy on children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The study included 364 children aged 4 to 7 and compared music therapy with enhanced standard care. The results showed no significant difference in the improvement of autism symptoms between the two groups, as measured by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). While the trial had a robust design with a large sample size and a narrow age range, it contrasted with previous smaller studies and a Cochrane meta-analysis that had suggested music therapy benefits. The study’s pragmatic design may have diluted the potential impact of music therapy by including a diverse population and allowing flexible treatment schedules. Despite these findings, the authors suggest that the results do not necessarily rule out the value of music therapy for ASD and recommend further research with more controlled settings and patient-centred outcomes[78].

- The case report by Radhakrishnan Nair S K et al. (2021), describes the treatment of a 7-year-old boy diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) using the homeopathic remedy Podophyllum peltatum. The boy exhibited symptoms such as poor communication, lack of social interaction, repetitive behaviors, and hyperactivity. The Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA) was used to measure the severity of his autism, with a baseline score of 110 indicating moderate autism. After four months of individualized treatment, the score dropped to 52, showing significant improvement. By the end of one year, the child’s score reduced to 7, suggesting a near-complete recovery. The report emphasizes the importance of individualized treatment in homoeopathy and highlights the potential of Podophyllum peltatum as an effective remedy for ASD symptoms, though it calls for further studies to validate these findings. No adverse effects were reported[79].

DISCUSSION:

The neurodevelopmental disorder known as ASD is receiving more and more attention from integrative and traditional health perspectives[80,81]. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and behavioural treatments like Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) are popular forms of treatment today, as are drugs like SSRIs and antipsychotics[82]. Additionally being investigated are integrative medicine techniques including herbal medicines, CBD oil, mindfulness exercises, dietary changes, and nutritional supplements[83]. These methods try to help autistic kids with their social skills, communication, anxiety, and emotional control. There is currently little data, nevertheless, about the efficacy of herbal remedies.There is a dearth of research on integrative strategies for ASD, and long-term randomised controlled studies are required to evaluate their efficacy and safety. Additionally absent are personalised therapeutic strategies like metabolic and genetic analysis. Furthermore, comorbidities, pharmaceutical side effects, and comprehensive outcome indicators have not been well-studied. For a thorough grasp of the effects of therapies, further research is required to evaluate family functioning, emotional health, and quality of life[84].Ethical questions of safety, effectiveness, informed consent, vulnerable groups, and equal access are brought up by herbal medicines, particularly in paediatric populations with ASD[85]. Because herbal supplements are sometimes not subject to the same strict regulations as pharmaceutical pharmaceuticals, children with sensitive or changed metabolisms may be in danger[86]. Parents who are dissatisfied with conventional methods may resort to alternative therapies, which might result in insufficient medical supervision. It is crucial to strike a balance between the child's entitlement to safe, quality care and the autonomy of the parents[87].

Although significant data is lacking, integrative medicine methods to treat ASD are becoming more popular. Ethical issues should be given top priority in future research, especially when it comes to paediatric populations.

CONCLUSION:

Treatments for autism spectrum disorder are covered in the review, including integrative medicine techniques like dietary interventions, nutritional supplements, mind-body therapies, and herbal remedies; behavioural therapies like ABA and CBT; and pharmaceutical treatments like anxiety and hyperactivity. There are still research gaps, though, such as the requirement for long-term studies on personalised medicine and moral questions around the safety of unapproved herbal medicines for minors and the possibility of exploitation.

Future directions to treat ASD:

Considering the use of genetic, metabolic, and neurological profiling to maximise responses to both pharmaceutical and integrative therapies, the demand for individualised treatments for ASD is growing. Prospective research should investigate

the standalone or adjunctive therapies of integrative therapies, such as herbal medicines, nutritional interventions, and mind-body activities, and evaluate their safety and efficacy through randomised controlled trials[88]. Potential links between gut health and symptoms of ASD might be investigated further in the gut-brain axis in ASD, which includes probiotics and nutritional supplements. Besides behavioural and cognitive results, research should examine the mental health, family relationships, and quality of life of people with ASD and their careers to better understand how interventions affect people in the real world. To enhance the results when treating the neurological and physical components of ASD, research should look at mixing integrative therapies like mindfulness, dietary interventions, and herbal therapies with standard behavioural therapy[89]. The use of cannabinoid oil to treat symptoms of ASD, such as anxiety, aggressiveness, and insomnia, is still in its infancy and requires further research on dose, safety, and efficacy in children[90]. Whereas regulatory agencies should carefully examine marketed medicines, including supplements or alternative cures, ethical research should provide clear rules for paediatric herbal and integrative treatments. With the potential to improve accessibility to ASD therapies, particularly for underprivileged communities, the COVID-19 pandemic has sped up the use of telemedicine and digital therapy platforms[91] which can be beneficial for the population.

REFERENCES

- Salari N, Rasoulpoor S, Rasoulpoor S, Shohaimi S, Jafarpour S, Abdoli N, et al. The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48:112.

- Hartman RE, Patel D. Personalized Food Intervention and Therapy for Autism Spectrum Disorder Management. Adv Neurobiol. 2020;24:547–71.

- Hirota T, King BH. Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. Jama. 2023;329:157–68.

- Chiarotti F, Venerosi A. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders: A review of worldwide prevalence estimates since 2014. Brain Sci. 2020;10: 274.

- Hodges H, Fealko C, Soares N. Autism spectrum disorder: Definition, epidemiology, causes, and clinical evaluation. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9:S55–65.

- Nair SK, Gilla D, Devasia MN. Autism Spectrum Disorder treated with Podophyllum peltatum-A Case Report. International Journal of AYUSH Case Reports. 2021 Dec 25;5:298-305.

- Campisi L, Imran N, Nazeer A, Skokauskas N, Azeem MW. Autism spectrum disorder. Br Med Bull. 2018;127:91–100.

- J. M, P. H. Autism spectrum disorders in genetic syndromes: Implications for diagnosis, intervention and understanding the wider autism spectrum disorder population. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009;53:852–73.

- Volden J. Autism Spectrum Disorder. Perspect Pragmatics, Philos Psychol. 2017;11:59–83.

- Germain B, Eppinger MA, Mostofsky SH, Dicicco-Bloom E, Maria BL. Recent Advances in Understanding and Managing Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:1887–920.

- Samsam M, Ahangari R, Naser SA. Pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorders: Revisiting gastrointestinal involvement and immune imbalance. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9942–51.

- Doyle CA, McDougle CJ. Pharmacologic treatments for the behavioral symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders across the lifespan. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:263–79.

- Sharma SR, Gonda X, Tarazi FI. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Classification, diagnosis and therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;190:91–104.

- Saxena V, Chacko G, Saxena U. Systematic review of the effectiveness of homoeopathy in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Clin Arch Commun Disord. 2021;6:1–

- Gilla D, Thrivikraman SK, Pillai PEP. A Case of Autism Spectrum Disorder Treated with Theridion currasavicum Prescribed on the Basis of Group Approach. Homœopathic Links. 2024;37:159–63.

- Ferreira ML, Loyacono N. Rationale of an advanced integrative approach applied to autism spectrum disorder: Review, discussion and proposal. J Pers Med. 2021;11:514.

- Radhakrishnan Nair SK, Gilla D, Devasia MN. Utility of individualised homoeopathic medicines in improving social interaction in childhood autism: A prospective, open-label, single arm study. Indian Journal of Research in Homoeopathy. 2024;18:190-9.

- Veselinovi? A, Petrovi? S, Žiki? V, Suboti? M, Jakovljevi? V, Jeremi? N, et al. Neuroinflammation in autism and supplementation based on omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: A narrative review. Med. 2021;57:893.

- Mallya R, Naik B, Momin M. Application of Herbs and Dietary Supplements in ADHD Management. CNS Neurol Disord - Drug Targets. 2022;22:950–72.

- Naureen Z, Dhuli K, Medori MC, Caruso P, Manganotti P, Chiurazzi P, et al. Dietary supplements in neurological diseases and brain aging. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022;63:E174–88.

- Nogay NH, Nahikian-Nelms M. Effects of nutritional interventions in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: an overview based on a literature review. Int J Dev Disabil. 2023;69:811–24.

- Chang JPC, Su KP. Nutritional Neuroscience as Mainstream of Psychiatry: The Evidence-Based Treatment Guidelines for Using Omega-3 Fatty Acids as a New Treatment for Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2020;18:469–83.

- Önal S, Sachadyn-Król M, Kostecka M. A Review of the Nutritional Approach and the Role of Dietary Components in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Light of the Latest Scientific Research. Nutrients. 2023;15:4852.

- Pistollato F, Forbes-Hernández TY, Calderón Iglesias R, Ruiz R, Elexpuru Zabaleta M, Cianciosi D, et al. Pharmacological, non-pharmacological and stem cell therapies for the management of autism spectrum disorders: A focus on human studies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;152:104579.

- Asgharian P, Quispe C, Herrera-Bravo J, Sabernavaei M, Hosseini K, Forouhandeh H, et al. Pharmacological effects and therapeutic potential of natural compounds in neuropsychiatric disorders: An update. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:926607.

- Grosso C, Santos M, Barroso MF. From Plants to Psycho-Neurology: Unravelling the Therapeutic Benefits of Bioactive Compounds in Brain Disorders. Antioxidants. 2023;12:1603.

- Mony TJ, Elahi F, Choi JW, Park SJ. Neuropharmacological Effects of Terpenoids on Preclinical Animal Models of Psychiatric Disorders: A Review. Antioxidants. 2022;11:1834.

- Singh S, Singh A, Kumar A, Chaurasia RN. Traditional medicines for mental health. InAntioxidants Funct Foods Neurodegener Disord Uses Prev Ther. 2021;387–97.

- Alqahtani SM. A Multi-Target mechanism of Withania somnifera bioactive compounds in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Treatment: Network pharmacology, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations studies. Arab J Chem. 2024;17:105772.

- Singh A, Garg P, Srivastava P. Identification of priority genes involved in ADHD using multiple system biology approach and establishment of Asiatic acid as a natural inhibitor against GRIN2B receptor. Informatics Med Unlocked. 2023;40:101282.

- Esposito D, Belli A, Ferri R, Bruni O. Sleeping without prescription: Management of sleep disorders in children with autism with non-pharmacological interventions and over-the-counter treatments. Brain Sci. 2020;10:1–30.

- Sachdeva P, Mehdi I, Kaith R, Ahmad F, Anwar MS. Potential natural products for the management of autism spectrum disorder. Ibrain. 2022;8:365–76.

- Babinska K, Celusakova H, Belica I, Szapuova Z, Waczulikova I, Nemcsicsova D, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and feeding problems and their associations with dietary interventions, food supplement use, and behavioral characteristics in a sample of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–18.

- Ujang Z, Nordin NI, Subramaniam T. Ginger Species and Their Traditional Uses in Modern Applications. J Ind Technol. 2015;23:59–70.

- Gupta S kumar, Sharma A. Medicinal properties of Zingiber officinale Roscoe - A Review. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2014;9:124–9.

- Rajput SB, Tonge MB, Karuppayil SM. An overview on traditional uses and pharmacological profile of Acorus calamus Linn. (Sweet flag) and other Acorus species. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:268–76.

- Singh R, Kumar Sharma P, Malviya R. Pharmacological Properties and Ayurvedic Value of Indian Buch Plant (Acorus calamus): A Short Review. Adv Biol Res (Rennes). 2011;5:145–54.

- Salari S, Amiri MS, Ramezani M, Moghadam AT, Elyasi S, Sahebkar A, et al. Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry, Traditional and Modern Uses of Actaea racemosa L. (Black cohosh): A Review. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1308:403–49.

- Nuntanakorn P, Jiang B, Einbond LS, Yang H, Kronenberg F, Weinstein IB, et al. Polyphenolic constituents of Actaea racemosa. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:314–8.

- Máthé Á. Indian Tobacco (Lobelia inflata L.). 2020;159–86.

- Subarnas A, Tadano T, Nakahata N, Arai Y, Kinemuchi H, Oshima Y, et al. A possible mechanism of antidepresant activity of beta-amyrin palmitate isolated from lobelia inflata leaves in the forced swimming test. Life Sci. 1993;52:289–96.

- Zhao DD, Jiang LL, Li HY, Yan PF, Zhang YL. Chemical components and pharmacological activities of terpene natural products from the genus paeonia. Molecules. 2016;21:1362.

- Parker S, May B, Zhang C, Zhang AL, Lu C, Xue CC. A Pharmacological Review of Bioactive Constituents of Paeonia lactiflora Pallas and Paeonia veitchii Lynch. Phyther Res. 2016;30:1445–73.

- Damanhouri ZA. A Review on Therapeutic Potential of Piper nigrum L. (Black Pepper): The King of Spices. Med Aromat Plants. 2014;03:161.

- Ashokkumar K, Murugan M, Dhanya MK, Pandian A, Warkentin TD. Phytochemistry and therapeutic potential of black pepper [Piper nigrum (L.)] essential oil and piperine: a review. Clin Phytoscience. 2021;7:52.

- Stupar RM, Specht JE. Insights from the Soybean (Glycine max and Glycine soja) Genome. Past, Present, and Future. Adv Agron. 2013;118:177–204.

- Ponnusha BS, Subramaniyam S, Pasupathi P, Subramaniyam B, Virumandy R, Sci. IJCBM. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial properties of Glycine Max-A review. Int J Curr Biol Med Sci [Internet]. 2011;1:49–62.

- Fischer E, Cachon R, Cayot N. Pisum sativum vs Glycine max, a comparative review of nutritional, physicochemical, and sensory properties for food uses. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;95:196–204.

- Manosroi A, Chankhampan C, Kietthanakorn BO, Ruksiriwanich W, Chaikul P, Boonpisuttinant K, et al. Pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical biological activities of hemp (Cannabis sativa L var. sativa) leaf and seed extracts. Chiang Mai J Sci. 2019;46:180–95.

- Sadegh A, Hossein M, Badi Hasanali N, MohammadReza N, SeyyedAliReza S. A Review on Agronomic, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Aspects of Cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.). J Med Plants. 2019;2(70):1–20.

- Zhang J, Wu C, Gao L, Du G, Qin X. Astragaloside IV derived from Astragalus membranaceus: A research review on the pharmacological effects. Adv Pharmacol. 2020;87:89–112.

- Jin M., Zhao K., Huang Q., Shang P. Structural features and biological activities of the polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014;64:257–66.

- Pehlivan M, Sevindik M. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Salvia multicaulis. Turkish J Agric - Food Sci Technol. 2018;6:628–31.

- Uysal I, Koçer O, Mohammed FS, Lekesiz Ö, Do?an M, ?abik AE, et al. Pharmacological and Nutritional Properties: Genus Salvia. Adv Pharmacol Pharm. 2023;11:140–55.

- AL-SNAFI AE. Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Effects of Lepidium Sativum-a Review. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2019;11:1–10.

- Mali RG, Mahajan SG, Mehta AA. Lepidium sativum (Garden cress): a review of contemporary literature and medicinal properties. Orient Pharm Exp Med. 2007;7:331–5.

- Patel S, Verma N, Gauthaman K. Passiflora incarnata linn: A review on morphology, phytochemistry and pharmacological aspects. Pharmacogn Rev. 2009;3:186–92.

- Tiwari S, Singh S, Tripathi S, Kumar S. A Pharmacological Review: Passiflora Species . Asian J Pharm Res. 2015;5:195.

- Bhattacharya A, Tiwari P, Sahu PK, Kumar S. A review of the phytochemical and pharmacological characteristics of Moringa oleifera. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2018;10:181–91.

- Pareek A, Pant M, Gupta MM, Kashania P, Ratan Y, Jain V, et al. Moringa oleifera: An Updated Comprehensive Review of Its Pharmacological Activities, Ethnomedicinal, Phytopharmaceutical Formulation, Clinical, Phytochemical, and Toxicological Aspects. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:2098.

- Hamre HJ, Glockmann A, von Ammon K, Riley DS, Kiene H. Efficacy of homoeopathic treatment: Systematic review of meta-analyses of randomised placebo-controlled homoeopathy trials for any indication. Syst Rev. 2023;12:191.

- Balkrishna A, Bhatt A Ben, Singh P, Haldar S, Varshney A. Comparative retrospective open-label study of ayurvedic medicines and their combination with allopathic drugs on asymptomatic and mildly-symptomatic COVID-19 patients. J Herb Med. 2021;29:100472.

- Iqbal J, Khan AA, Aziz T, Ali W, Ahmad S, Rahman SU, et al. Phytochemical Investigation, Antioxidant Properties and In Vivo Evaluation of the Toxic Effects of Parthenium hysterophorus. Molecules. 2022;27:4189.

- Srivastava A, Shivakumar GC, Pathak S, Ingle E, Kumari A, Shivakumar S, et al. Evidence-based effectiveness of herbal treatment modality for recurrent aphthous ulcers – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2021;12:303–10.

- Jo HG, Kim H, Baek E, Lee D, Hwang JH. Efficacy and Key Materials of East Asian Herbal Medicine Combined with Conventional Medicine on Inflammatory Skin Lesion in Patients with Psoriasis Vulgaris: A Meta-Analysis, Integrated Data Mining, and Network Pharmacology. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16:1160.

- Chien TJ, Liu CY, Chang YI, Fang CJ, Pai JH, Wu YX, et al. Therapeutic effects of herbal-medicine combined therapy for COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:950012.

- Saggar S, Mir PA, Kumar N, Chawla A, Uppal J, Shilpa S, et al. Traditional and Herbal Medicines: Opportunities and Challenges. Pharmacognosy Res. 2022;14:107–14.

- Subramanian DK, Balakrishnan G. Pharmacovigilance Consideration for Ayurvedic Medicines in Pediatric Practice: Developing Protocols for Documenting Clinical Safety. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2024;23:0976500X241276311.

- Romero-García PA, Ramirez-Perez S, Miguel-González JJ, Guzmán-Silahua S, Castañeda-Moreno JA, Komninou S, et al. Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Practices: A Narrative Review Elucidating the Impact on Healthcare Systems, Mechanisms and Paediatric Applications. Healthc. 2024;12:1547.

- Moussavi N, Mounkoro PP, Dembele SM, Ballo NN, Togola A, Diallo D, et al. Polyherbal Combinations Used by Traditional Health Practitioners against Mental Illnesses in Bamako, Mali, West Africa. Plants. 2024;13:454.

- Kim S, Nadar RM, DeRuiter J, Pathak S, Ramesh S, Moore T, et al. Mycotherapeutics Affecting Dopaminergic Neurotransmission to Exert Neuroprotection. Mushrooms with Ther Potentials. 2023;369–92.

- Puri V, Kanojia N, Sharma A, Huanbutta K, Dheer D, Sangnim T. Natural product-based pharmacological studies for neurological disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1011740.

- Scahill L, Shillingsburg MA, Ousley O, Pileggi ML, Kilbourne RL, Buckley D, et al. A Randomized Trial of Direct Instruction Language for Learning in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61:772–81.

- Scahill L, McDougle CJ, Aman MG, Johnson C, Handen B, Bearss K, et al. Effects of risperidone and parent training on adaptive functioning in Children with Pervasive Developmental Disorders and serious behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:136–46.

- S. B, K. B, P. A, A. B, R.L. H. A pilot randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids for autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord [Internet]. 2011;41:545–54.

- Aman MG, Findling RL, Hardan AY, Hendren RL, Melmed RD, Kehinde-Nelson O, et al. Safety and efficacy of memantine in children with autism: Randomized, placebo-controlled study and open-label extension. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:403–12.

- D. G, J. T, D.R. D, A.E. W, M.S. A, J.J. B. Randomized trial of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for children with autism. Res Autism Spectr Disord [Internet]. 2010;4:268–75.

- Broder-Fingert S, Feinberg E, Silverstein M. Music therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2017;318:523–4.

- Kudukayil S, Nair R, Gilla D, Devasia MN. Autism Spectrum Disorder treated with Podophyllum peltatum- A Case Report. Int J AYUSH Case Reports. 2021;5:298–305.

- Levy SE, Hyman SL. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17:803–20.

- Marazziti D, Carpita B, Palermo S, Parra E, Dell’Osso L. Microbiota, Immune System and Autism Spectrum Disorders: An Integrative Model Towards Novel Treatment Options. Eur Psychiatry. 2022;65:S63–4.

- Aishworiya R, Valica T, Hagerman R, Restrepo B. An Update on Psychopharmacological Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Focus (Madison). 2024;22:198–211.

- Höfer J, Hoffmann F, Bachmann C. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism. 2017;21:387–402.

- Gbedawo H. Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Framework for Integrative Pediatric Medicine. Integr Neurol. 2020;378–401.

- Becker DK. Pediatric Integrative Medicine. Prim Care - Clin Off Pract. 2017;44:337–50.

- Tsao JCI, Zeltzer LK. Complementary and alternative medicine approaches for pediatric pain: A review of the state-of-the-science. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2005;2:149–59.

- Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Neurol. 2014;4:177.

- Damiano CR, Mazefsky CA, White SW, Dichter GS. Future Directions for Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:828–43.

- Poustka L, Kamp-Becker I. Current practice and future avenues in autism therapy. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;30:357–78.

- Jack A, A. Pelphrey K. Annual Research Review: Understudied populations within the autism spectrum – current trends and future directions in neuroimaging research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2017;58:411–35.

- Oberman LM, Enticott PG, Casanova MF, Rotenberg A, Pascual-Leone A, Mccracken JT, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in autism spectrum disorder: Challenges, promise, and roadmap for future research. Autism Res. 2016;9:184–203

Prathibha G S* 1

Prathibha G S* 1

Mohit K 2

Mohit K 2

Srinivas B S 3

Srinivas B S 3

Madhu Parappanavar 4

Madhu Parappanavar 4

Rakshitha R 5

Rakshitha R 5

N K Jeevitha 6

N K Jeevitha 6

Debayan Bhattacharjee 7

Debayan Bhattacharjee 7

10.5281/zenodo.14171351

10.5281/zenodo.14171351