Abstract

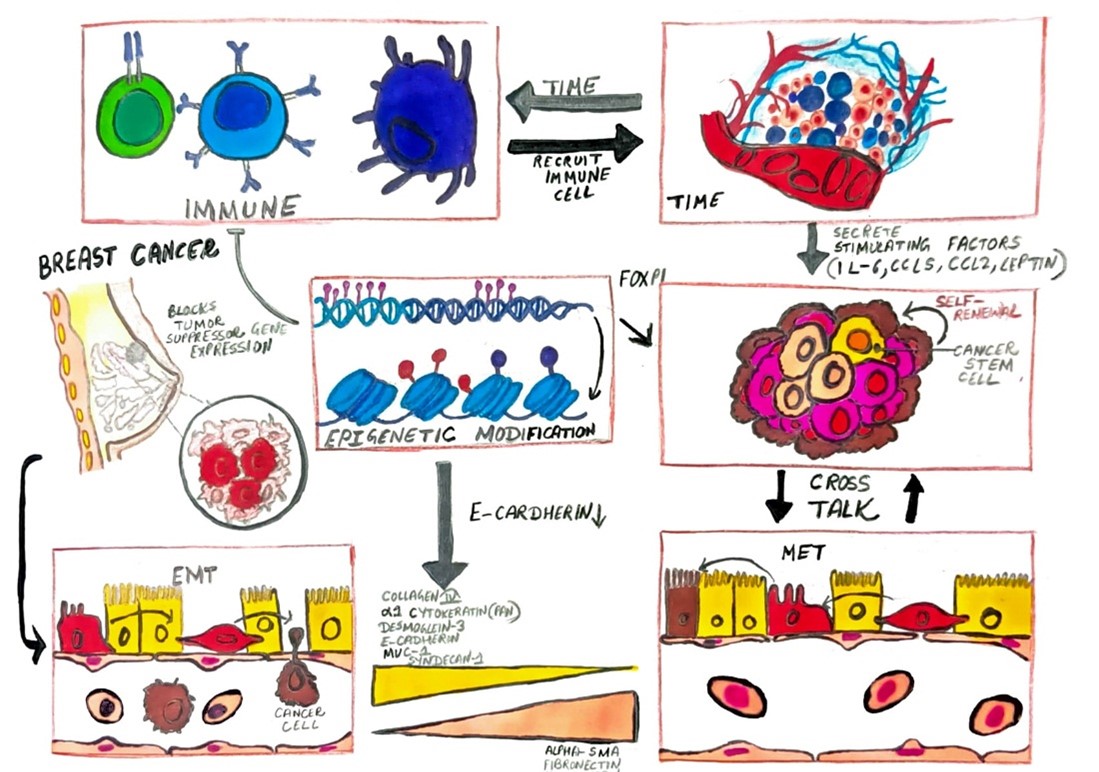

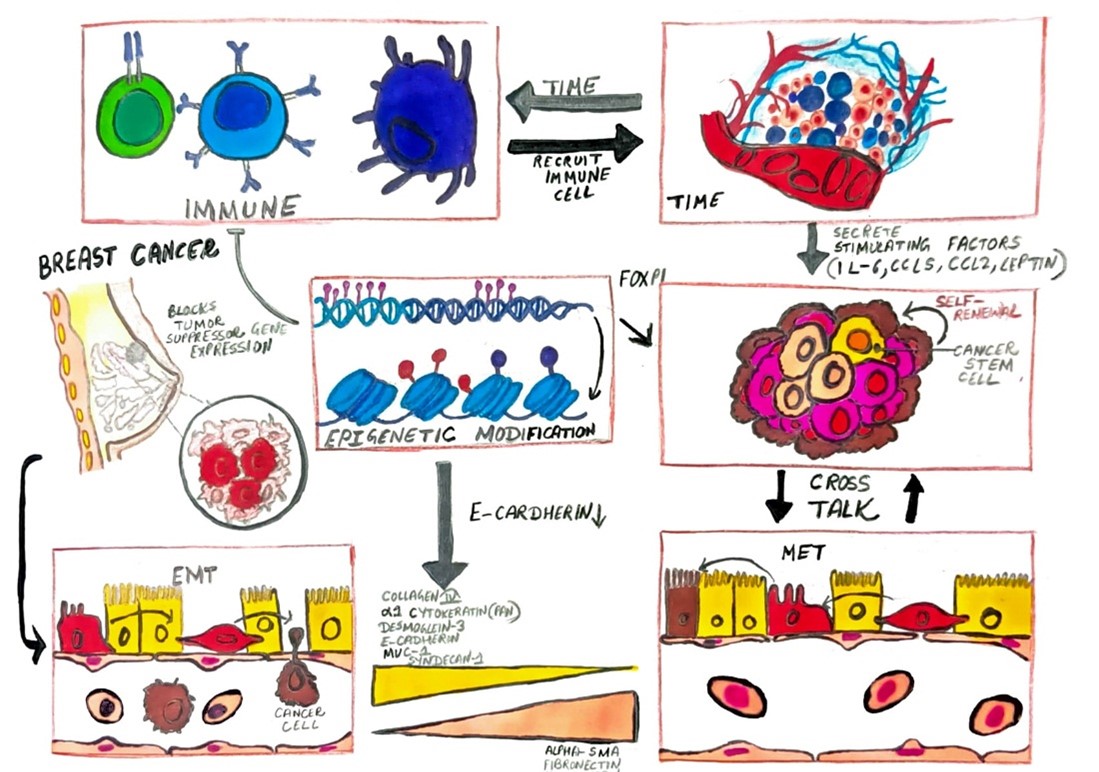

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of mortality among women globally, characterized by uncontrolled epithelial cell proliferation within breast tissue. This malignancy exhibits a range of histological subtypes, including invasive ductal and lobular carcinomas, and poses significant challenges in public health due to its complex biology and diverse clinical manifestations. Epidemiological data show higher incidence rates in developed countries, with genetic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 notably increasing susceptibility. Hormonal influences and environmental factors further complicate risk assessment. The pathogenesis of breast cancer involves genetic and epigenetic alterations leading to malignant transformation, with critical molecular pathways such as HER2/neu and PI3K/AKT/mTOR playing pivotal roles. The metastatic process is facilitated by mechanisms including epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, with heparanase and integrins significantly contributing to metastasis. Recent advancements in circulating tumor cell (CTC) analysis offer promising insights into early detection and monitoring of metastasis. Tumor-induced pre-metastatic niches and angiogenesis also play crucial roles in the metastatic cascade. Despite progress in treatment strategies, including chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapies, metastatic breast cancer remains challenging to cure. Ongoing research aims to enhance early detection, refine therapeutic approaches, and improve patient outcomes.

Keywords

Breast Cancer, Metastasis, HER2/neu Pathway, PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway, Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition, Circulating Tumor Cells, Heparanase, Angiogenesis, Pre-Metastatic Niche, Targeted Therapy,

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common and fatal malignancies affecting women worldwide [1]. This disease is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of cells within breast tissue, originating from various epithelial cells, and can present as several histological subtypes, including invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma. Despite advancements in early detection and treatment, breast cancer remains a significant public health concern due to its complex biology and varied clinical manifestations [2-4]. The epidemiology of breast cancer reveals significant geographic variation, with higher incidence rates in developed countries compared to developing regions. It is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women and ranks as the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally [5-7]. Risk factors for breast cancer are multifactorial, involving genetic predispositions, hormonal influences, and environmental factors. [8, 9] Notably, genetic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are linked to a higher risk of developing breast cancer due to their role in DNA repair [10, 11]. Other mutations in genes such as TP53 and PTEN also contribute to hereditary breast cancer syndromes [12, 13]. Hormonal factors, particularly the effects of estrogen and progesterone, are significant, with prolonged exposure through early menarche, late menopause, or hormone replacement therapy increasing risk. Additionally, environmental and lifestyle factors like obesity, physical inactivity, and alcohol consumption further influence breast cancer risk, interacting with genetic predispositions to complicate the disease [14-16].

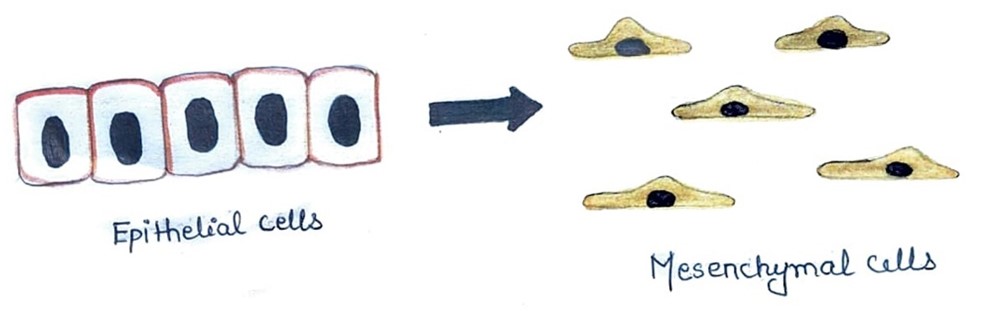

The pathogenesis of breast cancer involves a series of genetic and epigenetic changes that lead to malignant transformation. The progression from benign lesions, such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), to invasive cancer is marked by genomic instability and the disruption of key cellular pathways [17-19]. Crucial molecular pathways include the HER2/neu pathway, characterized by the overexpression of the HER2 protein, which is associated with more aggressive disease and poor prognosis but can be targeted with therapies like trastuzumab [20-22]. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, involved in regulating cell growth and metabolism, is also frequently altered, contributing to tumor progression and therapy resistance [23,24]. The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is another critical process, where epithelial cells gain mesenchymal traits, enhancing their ability to invade surrounding tissues and spread to distant sites [25-28]. This transition is controlled by transcription factors such as Snail, Twist, and ZEB1, which regulate cell adhesion and motility [29, 30]. Clinically, breast cancer may present with symptoms such as palpable lumps, changes in breast shape or texture, and abnormal nipple discharge, though it can also be asymptomatic and detected through screening [31, 32]. Diagnostic modalities include mammography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with mammography being the primary method for early detection. Histopathological analysis of biopsy specimens provides essential information about tumor type, grade, and receptor status, guiding therapeutic decisions [33-35]. Immunohistochemical staining for estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and HER2 is critical for determining prognosis and treatment strategies. [36, 37].Treatment for breast cancer involves a multidisciplinary approach, encompassing surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapies. Surgical options range from breast-conserving surgery to mastectomy, depending on tumor characteristics and patient preferences. Adjuvant therapies aim to eliminate residual disease and prevent recurrence, with chemotherapy and radiation playing key roles [38, 39]. Hormone therapy, including agents like tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, targets hormone receptor-positive tumors, while targeted therapies, such as HER2 inhibitors and CDK4/6 inhibitors, offer improved outcomes for specific molecular subtypes [40-43]. Future research is focused on further elucidating the molecular mechanisms of breast cancer and developing novel therapeutic approaches. Advances in genomics and proteomics are enhancing our understanding of tumor biology, paving the way for personalized medicine. Ongoing efforts aim to improve early detection, minimize treatment-related side effects, and enhance patient quality of life. Despite significant progress in diagnosis and treatment, breast cancer remains a complex and challenging disease, necessitating continued research and innovation to ultimately achieve a cure [44, 45].

Fig. 1. Mechanism of Breast Cancer

MECHANISMS

- The Role of Circulating Tumor Cells

The detection of breast cancer metastasis relies on clinical presentations of distant organ involvement, biopsies of affected tissues, radiological assessments, imaging techniques, and serum tumor markers [46, 47]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines for breast cancer follow-up and management list symptoms of recurrence as new breast lumps, bone, chest, or abdominal pain, dyspnea, and persistent headaches. ASCO also recommends mammography for early detection of relapse [48-50]. According to a study the importance of serum tumor markers in postoperative monitoring of breast cancer patients. They suggest intensive postoperative follow-up including consultations every 4-6 months, physical examinations, and evaluations of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), tissue polypeptide antigen (TPA), and breast cancer-associated antigen 115 D8/DF3 (CA15.3) [51-53]. Imaging methods such as bone scintigraphy, liver echography, and chest X-ray are recommended biannually, with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging performed if earlier methods raise suspicion [54, 55]. Although mammographic screening has reduced mortality by facilitating early diagnosis, the aforementioned methods often fall short in detecting metastasis at the earliest stages and in accurately predicting clinical outcomes [56, 57]. An emerging method for metastasis detection is the analysis of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), which shows promise in addressing the limitations of other diagnostic techniques [58, 59]. CTCs are tumor cells originating from primary sites or metastases that circulate in the bloodstream and are rarely found in healthy individuals. They play crucial roles in carcinoma metastasis, enabling prediction of metastatic relapse and disease progression. CTCs are typically isolated and enriched using either morphological or immunological techniques [60-62]. Morphological-based isolation separates CTCs by size discrepancies or density, while immunological techniques, which are more widely used, employ immunomagnetic isolation targeting epithelial cell-specific markers or tumor markers specific to cancer types [63-65]. After isolation, the source and genetic composition of CTCs are characterized using nucleic acid-based methods, such as quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), or cytometric-based methods, such as flow cytometry and enzyme-linked immunospot assay technology [66-68]. Clinical applications of CTC analysis have shown promising results. A specific research proposed that the number of CTCs could indicate ongoing metastasis [69, 70]. Evidence suggests that CTC counts correlate with clinical outcomes and survival in cancer patients. A study on patients with metastatic breast cancer before treatment found that those with more than five CTCs in 7.5 ml of blood had shorter progression-free and overall survival [71, 72]. A particular research demonstrated that the presence of one CTC in 7.5 ml blood after neoadjuvant chemotherapy could predict metastatic relapse. Despite promising results, the increasing number of CTC detection methods calls for standardization to ensure increased efficacy and quality [73, 74].

Fig. 2. Circulating Tumor Cells in the blood Stream

- The Metastatic Cascade and Invasion Mechanisms in Breast Cancer

The metastatic process involves a series of sequential steps. Failure to complete any of these steps halts the process. Metastasis begins with the local invasion of surrounding host tissue by cells originating from the primary tumor, followed by intravasation into blood or lymphatic vessels [75-77]. Tumor cells are then disseminated via the bloodstream or lymphatic system to distant organs, where they undergo cell cycle arrest and adhere to capillary beds within the target organ [78-80]. This is followed by extravasation into the organ parenchyma, proliferation, and promotion of angiogenesis [81-83]. Throughout these steps, tumor cells must evade the host’s immune response and apoptotic signals to survive. If successful, the process can be repeated to produce secondary metastases or ‘metastasis of metastases [84, 85].

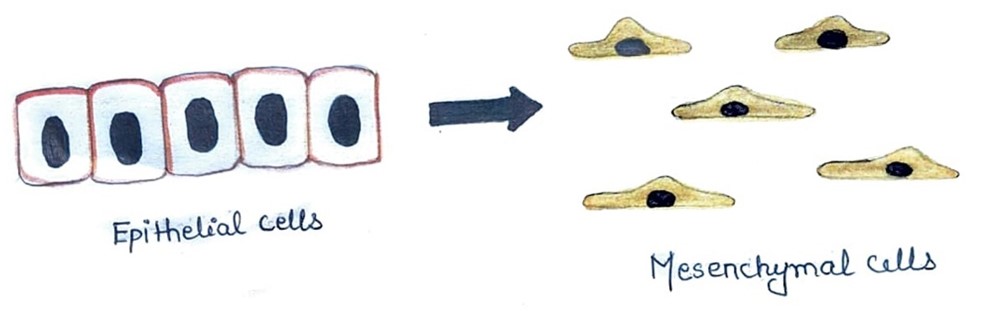

- Invasion

Metastasis begins with the invasion of tumor cells into surrounding host tissue. Invasive tumor cells must alter cell-to-cell adhesion and adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) [86]. The cadherin family plays a significant role in mediating cell-to-cell adhesion and is pivotal in breast cancer metastasis [87]. E-cadherin maintains cell-cell junctions, and its down-regulation is a determinant in the outgrowth of metastatic breast cancer cells. This down-regulation is associated with progression and metastasis in breast cancer, reflecting poor prognosis [88]. Mutations in E-cadherin that lead to functional loss are found in lobular breast carcinoma. N-cadherin, associated with mesenchymal cells, is related to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during the gastrulation stage [89, 90]. EMT is increasingly linked to cancer progression, aiding invasion and intravasation into the bloodstream and inducing proteases involved in ECM degradation. N-cadherin expression in place of E-cadherin leads to fibrosis and cyst formation in mammary glands, eventually resulting in malignant breast tumors in mice [91-93]. Down-regulation of E-cadherin and up-regulation of N-cadherin are frequently observed in most epithelial cancers during stromal invasion [94, 95]. Loss of E-cadherin reduces adhesion between epithelial breast cancer cells, while increased N-cadherin promotes adhesion to stromal cells, facilitating invasion into the stroma [96, 97]. Tumor cell adhesion to the ECM is mediated by integrins, transmembrane receptors found on ECM components such as fibronectin, laminin, collagen, fibrinogen, and vitronectin [98, 99]. Invasion is preceded by ECM degradation to penetrate tissue boundaries [100]. This degradation is mainly carried out by metalloproteinases (MMPs) and the urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) system [101]. In breast cancer patients, uPA is prognostically important for predicting the risk of distant metastases, even in patients with a good prognosis at diagnosis [102, 103]. Inhibition of uPA via small-interfering RNA (siRNA) restricts invasion and reduces MMP9 expression [104]. MMPs mediate ECM proteolysis at the invadopodial front of invasive breast cancer cell lines. Integrins also modulate tumor motility by participating in ECM-degrading enzyme activities, such as those of the MMPs. For instance, integrins ?5?1 and ?3?1 up-regulate MMP9 [105-107].

Fig. 3. Schematic showing the metastasis cascade of breast cancer

- Role of Heparanase in ECM Degradation and Breast Cancer Metastasis

Heparanase, a ?-glucuronidase, contributes to the degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) by breaking down heparan sulfate proteoglycan. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans, found in the ECM and on cell surfaces, are crucial for ECM assembly, integrity, cell matrix adhesion, and growth factor receptor interactions [108-110]. Heparan sulfate acts as a reservoir for heparin-binding growth factors and angiogenic factors. By degrading heparan sulfate, heparanase releases these substances, promoting tumor growth, invasion, and angiogenesis [111,112]. The expression of heparanase correlates with metastatic potential in breast cancer, and increased levels of heparan sulfate proteoglycans, such as glypican-1 and syndecan-1, are observed in advanced stages of breast cancer. Additionally, the overexpression of heparanase in MCF7 breast cancer cells has been shown to enhance cell proliferation, survival, and stromal infiltration both in vitro and in vivo [113-115].

- Migration and Motility in Tumor Cell Invasion

To achieve an invasive phenotype, tumor cells must migrate from the primary site. They can migrate either singly or in coordination. Coordinated migration is common in intermediate or highly differentiated lobular carcinomas of the breast [116, 117]. It is suggested that coordinated migration may switch to single-cell migration, particularly in poorly differentiated tumors, due to abnormalities in intercellular adhesion proteins [118]. Tumor cells that migrate collectively require intercellular junctions and often circulate as emboli in the blood or lymphatic vessels after invasion and intravasation [119, 120]. Cells at the leading edge of the migrating tumor create tube-like microtracks by cleaving and orienting collagen fibers using membrane type 1 (MT1) MMP, facilitating collective migration through the ECM [121, 122]. In contrast, single tumor cells migrate via two main mechanisms: protease-dependent mesenchymal movement or protease-independent amoeboid movement [123]. The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a critical pathway for the mesenchymal movement of single migratory cells [124, 125]. During EMT, cells transition from an epithelial phenotype to a mesenchymal-like phenotype, losing epithelial markers like E-cadherin and expressing mesenchymal markers such as vimentin [126]. This process involves transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin, including ZEB1, ZEB2, Twist, Snail, and Slug, which are linked to signaling pathways such as TGF-?, WNT, and PI3K/AKT [127-130]. These repressors are associated with poor prognosis in breast carcinoma. Following the loss of cell adhesion, cells alter their polarity from apical-basal to front-rear, initiating migration through changes in cortical actin and actin stress fibers that remodel the cytoskeleton. Proteolytic enzymes like MMPs are activated, altering cell-matrix adhesion. Cells undergoing EMT adopt an elongated fibroblast-like shape, moving through ECM channels created by matrix-degrading enzymes like MMPs [131, 132]. In contrast, cells with amoeboid movement are round and resemble primordial unicellular organisms. They push and squeeze through matrix pores, relying on shape deformations and structural changes in the ECM rather than actual degradation. These cells are loosely attached to the ECM, lose cell polarity, and move through paths of least resistance. The mechanical force for amoeboid movement is generated by active myosin/actin contractions and cortical actin via signaling pathways such as RhoA/Rho kinase (ROCK) [133-135].

- Regulation of Tumor Cell Migration Modes: Mesenchymal-to-Amoeboid Transition and Amoeboid-to-Mesenchymal Transition

Tumor cells predominantly employ mesenchymal motility for migration. However, under specific conditions, changes in molecular pathways can lead to a shift in migration mode. This shift can occur either from mesenchymal to amoeboid movement, known as mesenchymal-to-amoeboid transition (MAT), or from amoeboid to mesenchymal movement, termed amoeboid-to-mesenchymal transition (AMT) [136, 137]. At the molecular level, AMT is induced by the inhibition of pro-amoeboid pathways, such as those involving Rho/ROCK, PI3K, and cell division control protein 42 homolog (CDC42) [138, 139]. Conversely, molecules such as ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate (Rac) and SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (Smurf1), which promote mesenchymal movement, are associated with MAT. Additionally, inhibition of pericellular proteolysis or elevated levels of Rho/ROCK signaling can also drive MAT [140-142]. The spatial organization of collagen fibers in the tumor extracellular matrix (ECM) boundary influences the migration mode of tumor cells [143-144]. When collagen fibers are pre-aligned perpendicularly to the ECM boundary, amoeboid movements of MDA-MB-231 mesenchymal cells do not engage the Rho/ROCK pathway. However, if collagen fibers are not aligned with the tumor ECM boundary, activation of the Rho/ROCK pathway is observed in these cells [145-147].

- Role of Stromal Cells and Tumor Microenvironment in Tumor Cell Migration and Metastasis

Stromal cells play a significant role in facilitating tumor cell migration. In breast cancer, the predominant stromal cells are fibroblasts, often referred to as carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [148, 149]. Conditioned media derived from CAFs has been shown to enhance cell motility and invasion in breast cancer models in vitro [150-151]. Furthermore, studies in immunodeficient nude mice have demonstrated that injection of human CAFs along with MCF7-ras human breast cancer cells leads to increased tumor growth and angiogenesis compared to injection with normal human fibroblasts [151, 152].

- Tumor Microenvironment

Stephen Paget's 'seed and soil' theory of metastasis, proposed in the 1980s, posits that tumor cells ('seeds') can only grow when they encounter a favorable environment ('soil'). This theory is being reevaluated, with growing evidence highlighting the tumor microenvironment as a crucial determinant of metastasis [153, 154]. The microenvironment is essential for tumor cell proliferation, and a supportive microenvironment is necessary for tumor growth and malignant progression. The tumor microenvironment comprises various specialized cells, including fibroblasts, immune cells, endothelial cells, and mural cells of blood and lymphatic vessels, as well as the extracellular matrix (ECM) [155-158]. These components collectively influence tumor progression. Malignant cells interact continuously with microenvironmental cells at both primary and metastatic sites, facilitating the transition from 'in situ' to metastatic breast cancer. For instance, macrophages recruited by non-invasive breast tumor cells can induce angiogenesis and promote malignant transformation [159, 160]. Tissue-associated macrophages, which impact tumor invasion, angiogenesis, immune evasion, and migratory behavior, form interactive niches with breast cancer cells and endothelial cells, aiding in intravasation and metastatic spread [161-163]. In bone, interactions between tumor cells and stromal components, such as osteoclasts and osteoblasts, affect tumor cell growth and dormancy. Consequently, the successful outgrowth of metastatic cells in bone is heavily influenced by the bone stroma [164-165].

- Tumor-Induced Pre-Metastatic Niche Formation and Tissue Tropism in Breast Cancer Metastasis

It is proposed that tumor cells may secrete factors to modify the microenvironment and create a 'pre-metastatic niche' that facilitates future metastasis. A research demonstrated that signals from the primary tumor can induce the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) in lung endothelial cells and macrophages before metastasis occurs, thereby promoting the preferential invasion of tumor cells into the lungs [166, 167]. Additionally, clusters of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR-1)-positive hematopoietic progenitor cells were identified in pre-metastatic lymph nodes of breast cancer patients prior to the arrival of tumor cells, indicating the establishment of a pre-metastatic niche [168, 169]. Breast cancer is known to predominantly metastasize to the bone and lungs, while metastasis to other organs such as the liver and brain is less frequent [170, 171]. Gene expression profiles associated with the preferential metastasis of breast cancer cells to bone marrow and lungs have been identified, suggesting that metastasis exhibits tissue-specific tropism [172, 173]. Furthermore, chemokines play a role in directing tumor cells to specific organs. For instance, breast cancer tissues express high levels of the chemokine receptor CXCR4, while its ligand, CXCL12, is predominantly expressed in lymph nodes, lungs, liver, and bone marrow, but at lower levels in the small intestine, kidney, brain, skin, and skeletal muscle [174, 175]. Organs with elevated CXCL12 expression are common sites for breast cancer metastasis. Muller et al. demonstrated that the interaction between CXCR4 and CXCL12 facilitates the migration of breast cancer cells to these frequently targeted organs [176, 177].

Fig. 4. Epithelial–to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The epithelial cells undergo phenotypic changes to take on mesenchymal-like characteristics

- Role of Angiogenesis in Tumor Metastasis and the Angiogenic Switch

The development of tumor vasculature is a crucial factor in metastasis, as angiogenesis significantly contributes to tumor progression and the growth of metastases. Angiogenesis is considered a key adaptation of the tumor microenvironment and is recognized as a hallmark of cancer. During tumorigenesis, the equilibrium between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors becomes disrupted, favoring pro-angiogenic signalling [178-180]. This shift, often referred to as the 'angiogenic switch,' is driven by genetic mutations, mechanical stress, inflammatory responses, tumor expression of angiogenic proteins, and predominantly, hypoxia. Unlike normal physiological conditions, tumor vasculature is irregular and differs structurally, functionally, and genetically from healthy blood vessels. These abnormal blood vessels are inadequate in delivering sufficient oxygen to the tumor, leading to a state of tumor hypoxia. In response, tumor cells increase the production of pro-angiogenic factors, which further exacerbates the formation of dysfunctional vasculature. This creates a feedback loop where the persistent hypoxic environment triggers invasive and metastatic programs, promoting tumor progression and metastasis [181-183].

- Hypoxia-Induced Angiogenesis and the Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

Hypoxic conditions in tumors activate factors such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), which in turn stimulate the production of angiogenic proteins. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors (VEGFRs) are among the most extensively studied of these proteins. VEGF is a key member of a growth factor family that includes VEGF-A, -B, -C, -D, and -E, as well as placental growth factor. VEGF plays a critical role in both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, exerting its effects through various VEGFRs [184, 185]. It promotes endothelial cell proliferation, invasion, and migration, and increases microvascular permeability. The elevated expression of VEGF in solid tumors is often associated with poor prognosis and a higher propensity for metastasis [186, 187].

CURRENT STRATEGIES AND CHALLENGES IN THE TREATMENT OF METASTATIC BREAST CANCER

Despite significant advancements in treatment, metastatic breast cancer remains a largely incurable disease. Therapeutic approaches are generally categorized into standard chemotherapy and targeted therapies.

Standard Chemotherapy:

Traditional chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer includes the use of anthracyclines, taxanes, and 5-fluorouracil, often administered in a sequential manner. Anthracyclines, while effective, are associated with the risk of cardiac dysfunction. Newer cytotoxic agents such as epothilones and ixabepilone have shown increased efficacy in patients previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes [188, 189].

Targeted Therapies: This category encompasses hormone therapy, immunotherapy, and antiangiogenic therapy [190].

Hormone Therapy:

Hormone-based treatments aim to block estrogen receptors or reduce estrogen levels. Aromatase inhibitors, such as letrozole, anastrozole, and exemestane, inhibit the enzyme aromatase, which converts adrenal androgens to estrogen. Aromatase inhibitors have demonstrated superior therapeutic outcomes compared to tamoxifen, particularly as first-line treatments in post-menopausal women [191- 193].

Immunotherapy:

Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the extracellular domain of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2), is used to inhibit the growth of tumors overexpressing HER-2. When combined with chemotherapy, trastuzumab has been shown to improve overall survival rates, response rates, and progression-free survival. Newer HER-2-targeting antibodies, such as trastuzumab-MCC-DM1 and pertuzumab, are also showing promising results [194-196].

Antiangiogenic Therapy:

Antiangiogenic agents target the formation of new blood vessels, a process crucial for tumor growth. Bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), reduces endothelial cell proliferation and limits the tumor's blood supply. The combination of bevacizumab with other chemotherapeutic agents has been associated with increased progression-free survival. However, this therapy can also lead to adverse effects such as severe hypertension, bleeding, and heart failure [197-200].

CONCLUSION:

Breast cancer continues to be a significant global health issue, marked by its diverse histological subtypes, complex pathogenesis, and challenging clinical management. Despite substantial advancements in early detection and treatment modalities, the multifactorial nature of breast cancer, encompassing genetic, hormonal, and environmental risk factors, necessitates ongoing research and innovation. The progression from benign lesions to invasive carcinoma involves critical molecular pathways, such as HER2/neu and PI3K/AKT/mTOR, which underscore the complexity of tumor biology and contribute to resistance against conventional therapies. The metastatic cascade, driven by processes such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, is crucial for the spread of breast cancer cells. Emerging techniques for detecting circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and understanding their role in metastasis hold promise for earlier diagnosis and more effective monitoring of disease progression. Additionally, the formation of pre-metastatic niches and the role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis highlight the intricate interactions between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Despite the progress made in targeted therapies, hormone treatments, and antiangiogenic agents, metastatic breast cancer remains difficult to cure, underscoring the need for continued research. Future efforts should focus on refining detection methods, developing personalized treatment strategies, and improving patient outcomes through a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor progression and metastasis. The ultimate goal is to achieve more effective therapies that can significantly enhance survival rates and quality of life for patients with breast cancer.

REFERENCES

- Lacey Jr JV, Devesa SS, Brinton LA. Recent trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2002;39(2?3):82-8.

- Vamesu S. Angiogenesis and tumor histologic type in primary breast cancer patients: an analysis of 155 needle core biopsies. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2008 Jan 1;49(2):181-8.

- Saad HA, Baz A, Riad M, Eraky ME, El-Taher A, Farid MI, Sharaf K, Said HE, Ibrahim LA. Tumor microenvironment and immune system preservation in early-stage breast cancer: routes for early recurrence after mastectomy and treatment for lobular and ductal forms of disease. BMC immunology. 2024 Jan 25;25(1):9.

- Slater M, Danieletto S, Pooley M, Cheng Teh L, Gidley-Baird A, Barden JA. Differentiation between cancerous and normal hyperplastic lobules in breast lesions. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2004 Jan;83:1-0.

- Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment: a review. Jama. 2019 Jan 22;321(3):288-300.

- Kolak A, Kami?ska M, Sygit K, Budny A, Surdyka D, Kukie?ka-Budny B, Burdan F. Primary and secondary prevention of breast cancer. Annals of Agricultural and environmental Medicine. 2017;24(4).

- Lipworth L. Epidemiology of breast cancer. European journal of cancer prevention. 1995 Feb 1;4(1):7-30.

- Martin AM, Weber BL. Genetic and hormonal risk factors in breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000 Jul 19;92(14):1126-35.

- Laden F, Hunter DJ. Environmental risk factors and female breast cancer. Annual review of public health. 1998 May;19(1):101-23.

- Godet I, Gilkes DM. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and treatment strategies for breast cancer. Integrative cancer science and therapeutics. 2017 Feb;4(1).

- Shuen AY, Foulkes WD. Inherited mutations in breast cancer genes—risk and response. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 2011 Apr;16:3-15.

- Tonin PN. Genes implicated in hereditary breast cancer syndromes. InSeminars in Surgical Oncology 2000 Jun (Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 281-286). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

- Nakanishi A, Kitagishi Y, Ogura Y, Matsuda S. The tumor suppressor PTEN interacts with p53 in hereditary cancer. International journal of oncology. 2014 Jun 1;44(6):1813-9.

- Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Wan PC, Pike MC. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk: estrogen versus estrogen plus progestin. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000 Feb 16;92(4):328-32.

- Dall GV, Britt KL. Estrogen effects on the mammary gland in early and late life and breast cancer risk. Frontiers in oncology. 2017 May 26;7:110.

- Fournier A, Mesrine S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F. Estrogen-progestagen menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer: does delay from menopause onset to treatment initiation influence risks?. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009 Nov 1;27(31):5138-43.

- Logan GJ, Dabbs DJ, Lucas PC, Jankowitz RC, Brown DD, Clark BZ, Oesterreich S, McAuliffe PF. Molecular drivers of lobular carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Research. 2015 Dec;17:1-0.

- Rehman S. A study of the molecular pathology of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. University of London, University College London (United Kingdom); 2005.

- Hu M, Yao J, Carroll DK, Weremowicz S, Chen H, Carrasco D, Richardson A, Violette S, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Bauerlein EL. Regulation of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition. Cancer cell. 2008 May 6;13(5):394-406.

- Fiszman GL, Jasnis MA. Molecular mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance in HER2 overexpressing breast cancer. International journal of breast cancer. 2011;2011(1):352182.

- Nahta R, Esteva FJ. HER2 therapy: molecular mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance. Breast Cancer Research. 2006 Dec;8:1-8.

- Derakhshani A, Rezaei Z, Safarpour H, Sabri M, Mir A, Sanati MA, Vahidian F, Gholamiyan Moghadam A, Aghadoukht A, Hajiasgharzadeh K, Baradaran B. Overcoming trastuzumab resistance in HER2?positive breast cancer using combination therapy. Journal of cellular physiology. 2020 Apr;235(4):3142-56.

- Rascio F, Spadaccino F, Rocchetti MT, Castellano G, Stallone G, Netti GS, Ranieri E. The pathogenic role of PI3K/AKT pathway in cancer onset and drug resistance: an updated review. Cancers. 2021 Aug 5;13(16):3949.

- Guerrero-Zotano A, Mayer IA, Arteaga CL. PI3K/AKT/mTOR: role in breast cancer progression, drug resistance, and treatment. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2016 Dec;35:515-24.

- Prieto-García E, Díaz-García CV, García-Ruiz I, Agulló-Ortuño MT. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in tumor progression. Medical Oncology. 2017 Jul;34:1-0.

- Pearson GW. Control of invasion by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition programs during metastasis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019 May 10;8(5):646.

- Dongre A, Weinberg RA. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2019 Feb;20(2):69-84.

- Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: a historical overview. Translational oncology. 2020 Jun 1;13(6):100773.

- Lee JY, Kong G. Roles and epigenetic regulation of epithelial–mesenchymal transition and its transcription factors in cancer initiation and progression. Cellular and molecular life sciences. 2016 Dec;73:4643-60.

- Nieszporek A, Skrzypek K, Adamek G, Majka M. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. Acta Biochimica Polonica. 2019;66(4).

- Shetty MK. Imaging of the Symptomatic Breast. InBreast & Gynecological Diseases: Role of Imaging in the Management 2021 Jun 25 (pp. 27-79). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- McCool WF, Stone-Condry M, Bradford HM. Breast health care: a review. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1998 Nov 1;43(6):406-30.

- Berg WA, Gutierrez L, NessAiver MS, Carter WB, Bhargavan M, Lewis RS, Ioffe OB. Diagnostic accuracy of mammography, clinical examination, US, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of breast cancer. radiology. 2004 Dec;233(3):830-49.

- Barba D, León-Sosa A, Lugo P, Suquillo D, Torres F, Surre F, Trojman L, Caicedo A. Breast cancer, screening and diagnostic tools: All you need to know. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2021 Jan 1;157:103174.

- Sumkin JH, Berg WA, Carter GJ, Bandos AI, Chough DM, Ganott MA, Hakim CM, Kelly AE, Zuley ML, Houshmand G, Anello MI. Diagnostic performance of MRI, molecular breast imaging, and contrast-enhanced mammography in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Radiology. 2019 Dec;293(3):531-40.

- Jorns JM, Healy P, Zhao L. Review of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER-2/neu immunohistochemistry impacts on treatment for a small subset of breast cancer patients transferring care to another institution. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 2013 Nov 1;137(11):1660-3.

- Allred DC, Carlson RW, Berry DA, Burstein HJ, Edge SB, Goldstein LJ, Gown A, Hammond ME, Iglehart JD, Moench S, Pierce LJ. NCCN task force report: estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer by immunohistochemistry. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2009 Sep 1;7(Suppl_6):S-1.

- Moo TA, Sanford R, Dang C, Morrow M. Overview of breast cancer therapy. PET clinics. 2018 Jul 1;13(3):339-54.

- Burguin A, Diorio C, Durocher F. Breast cancer treatments: updates and new challenges. Journal of personalized medicine. 2021 Aug 19;11(8):808.

- Harbeck N, Burstein HJ, Hurvitz SA, Johnston S, Vidal GA. A look at current and potential treatment approaches for hormone receptor?positive, HER2?negative early breast cancer. Cancer. 2022 Jun 1;128:2209-23.

- Ballinger TJ, Meier JB, Jansen VM. Current landscape of targeted therapies for hormone-receptor positive, HER2 negative metastatic breast cancer. Frontiers in oncology. 2018 Aug 10;8:308.

- Aggelis V, Johnston SR. Advances in endocrine-based therapies for estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Drugs. 2019 Nov;79(17):1849-66.

- Nagini S. Breast cancer: current molecular therapeutic targets and new players. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents). 2017 Feb 1;17(2):152-63.

- Neilson HK, Friedenreich CM, Brockton NT, Millikan RC. Physical activity and postmenopausal breast cancer: proposed biologic mechanisms and areas for future research. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009 Jan 1;18(1):11-27.

- McCormick S, Brody J, Brown P, Polk R. Public involvement in breast cancer research: an analysis and model for future research. International Journal of Health Services. 2004 Oct;34(4):625-46.

- Duffy MJ. Serum tumor markers in breast cancer: are they of clinical value?. Clinical chemistry. 2006 Mar 1;52(3):345-51.

- Ugrinska A, Bombardieri E, Stokkel MP, Crippa F, Pauwels EK. Circulating tumor markers and nuclear medicine imaging modlities: Breast, prostate and ovarian cancer. The Quarterly Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2002 Jun 1;46(2):88.

- Hassett MJ, Somerfield MR, Baker ER, Cardoso F, Kansal KJ, Kwait DC, Plichta JK, Ricker C, Roshal A, Ruddy KJ, Safer JD. Management of male breast cancer: ASCO guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Jun 1;38(16):1849-63.

- Bodai BI, Tuso P. Breast cancer survivorship: a comprehensive review of long-term medical issues and lifestyle recommendations. The Permanente Journal. 2015;19(2):48.

- Goel MS, Didwania A. Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Management. Sex-and Gender-Based Women's Health: A Practical Guide for Primary Care. 2020:313-28.

- Nicolini A, Carpi A. Postoperative follow-up of breast cancer patients: overview and progress in the use of tumor markers. Tumor biology. 2000 Jun 30;21(4):235-48.

- Lempiäinen A. Forms of human chorionic gonadotropin in serum of testicular cancer patients.

- Noel LA, Langnas AN, DO RJ, Wood RP, Shaw BW. ASCP/CAP Pathology Resident Award Finalists.

- Daffner RH, Hartman M. Clinical radiology: the essentials. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013 Sep 6.

- Bychkovsky BL, Lin NU. Imaging in the evaluation and follow-up of early and advanced breast cancer: When, why, and how often?. The Breast. 2017 Feb 1;31:318-24.

- Tabár L, Dean PB, Chen TH, Yen AM, Chiu SY, Tot T, Smith RA, Duffy SW. The impact of mammography screening on the diagnosis and management of early-phase breast cancer. Breast cancer: a new era in management. 2014:31-78.

- Greenwald Z. The performance of mobile screening units in a breast cancer screening programme in southern Brazil. McGill University (Canada); 2016.

- Kowalik A, Kowalewska M, Gó?d? S. Current approaches for avoiding the limitations of circulating tumor cells detection methods—implications for diagnosis and treatment of patients with solid tumors. Translational Research. 2017 Jul 1;185:58-84.

- Lianidou ES, Markou A. Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer: detection systems, molecular characterization, and future challenges. Clinical chemistry. 2011 Sep 1;57(9):1242-55.

- Pantel K, Speicher MR. The biology of circulating tumor cells. Oncogene. 2016 Mar;35(10):1216-24.

- Roessler S, Jia HL, Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS, Sun Z, Tang ZY, Qin LX, Wang XW. A unique metastasis gene signature enables prediction of tumor relapse in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer research. 2010 Dec 15;70(24):10202-12.

- Arya SK, Lim B, Rahman AR. Enrichment, detection and clinical significance of circulating tumor cells. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13(11):1995-2027.

- Scully OJ, Bay BH, Yip G, Yu Y. Breast cancer metastasis. Cancer genomics & proteomics. 2012 Sep 1;9(5):311-20.

- Kling A. Thermoplastic microfluidic devices for the analysis of cancer biomarkers in liquid biopsies (Doctoral dissertation, ETH Zurich).

- Xie Y, Xu X, Wang J, Lin J, Ren Y, Wu A. Latest advances and perspectives of liquid biopsy for cancer diagnostics driven by microfluidic on-chip assays. Lab on a Chip. 2023;23(13):2922-41.

- Sun YF, Yang XR, Zhou J, Qiu SJ, Fan J, Xu Y. Circulating tumor cells: advances in detection methods, biological issues, and clinical relevance. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2011 Aug;137:1151-73.

- Lowes LE, Goodale D, Keeney M, Allan AL. Image cytometry analysis of circulating tumor cells. Methods in cell biology. 2011 Jan 1;102:261-90.

- Scully OJ, Bay BH, Yip G, Yu Y. Breast cancer metastasis. Cancer genomics & proteomics. 2012 Sep 1;9(5):311-20.

- Goodman Jr OB, Symanowski JT, Loudyi A, Fink LM, Ward DC, Vogelzang NJ. Circulating tumor cells as a predictive biomarker in patients with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Clinical genitourinary cancer. 2011 Sep 1;9(1):31-8.

- Goodman CR, Speers CW. The role of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer and implications for radiation treatment decisions. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 2021 Jan 1;109(1):44-59.

- Hayes DF, Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Miller MC, Matera J, Allard WJ, Doyle GV, Terstappen LW. Circulating tumor cells at each follow-up time point during therapy of metastatic breast cancer patients predict progression-free and overall survival. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006 Jul 15;12(14):4218-24.

- Bidard FC, Hajage D, Bachelot T, Delaloge S, Brain E, Campone M, Cottu P, Beuzeboc P, Rolland E, Mathiot C, Pierga JY. Assessment of circulating tumor cells and serum markers for progression-free survival prediction in metastatic breast cancer: a prospective observational study. Breast Cancer Research. 2012 Feb;14:1-0.

- Strati A, Markou A, Kyriakopoulou E, Lianidou E. Detection and molecular characterization of circulating tumour cells: challenges for the clinical setting. Cancers. 2023 Apr 6;15(7):2185.

- Brodie AM, Njar VC. Aromatase inhibitors in advanced breast cancer: mechanism of action and clinical implications. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 1998 Jul 1;66(1-2):1-0.

- Nguyen TH. Mechanisms of metastasis. Clinics in dermatology. 2004 May 1;22(3):209-16.

- Leong SP, Naxerova K, Keller L, Pantel K, Witte M. Molecular mechanisms of cancer metastasis via the lymphatic versus the blood vessels. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2022 Feb;39(1):159-79.

- Welch DR, Hurst DR. Defining the hallmarks of metastasis. Cancer research. 2019 Jun 15;79(12):3011-27.

- Cominetti MR, Altei WF, Selistre-de-Araujo HS. Metastasis inhibition in breast cancer by targeting cancer cell extravasation. Breast Cancer: Targets and Therapy. 2019 Apr 18:165-78.

- Rajput S, Sharma PK, Malviya R. Fluid mechanics in circulating tumour cells: role in metastasis and treatment strategies. Medicine in Drug Discovery. 2023 Jun 1;18:100158.

- Fidler IJ. Origin and biology of cancer metastasis. Cytometry: The Journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 1989 Nov;10(6):673-80.

- Paduch R. The role of lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis in tumor metastasis. Cellular oncology. 2016 Oct;39:397-410.

- Nagy JA, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. Vascular hyperpermeability, angiogenesis, and stroma generation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012 Feb 1;2(2):a006544.

- Urabe F, Patil K, Ramm GA, Ochiya T, Soekmadji C. Extracellular vesicles in the development of organ?specific metastasis. Journal of extracellular vesicles. 2021 Jul;10(9):e12125.

- Whiteside TL. Immune responses to malignancies. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010 Feb 1;125(2):S272-83.

- Benedict CA, Norris PS, Ware CF. To kill or be killed: viral evasion of apoptosis. Nature immunology. 2002 Nov 1;3(11):1013-8.

- Mizejewski GJ. Breast cancer, metastasis, and the microenvironment: Disabling the tumor cell-to-stroma communication network. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2019;5:35.

- Albergaria A, Ribeiro AS, Vieira AF, Sousa B, Nobre AR, Seruca R, Schmitt F, Paredes J. P-cadherin role in normal breast development and cancer. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2011 Nov 29;55(7-8-9):811-22.

- Wendt MK, Taylor MA, Schiemann BJ, Schiemann WP. Down-regulation of epithelial cadherin is required to initiate metastatic outgrowth of breast cancer. Molecular biology of the cell. 2011 Jul 15;22(14):2423-35.

- Van Aken E, De Wever O, da Rocha CA, Mareel M. Defective E-cadherin/catenin complexes in human cancer. Virchows Archiv. 2001 Dec;439:725-51.

- Petrova YI, Schecterson L, Gumbiner BM. Roles for E-cadherin cell surface regulation in cancer. Molecular biology of the cell. 2016 Nov 1;27(21):3233-44.

- Chiang SP, Cabrera RM, Segall JE. Tumor cell intravasation. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2016 Jul 1;311(1):C1-4.

- Pearson GW. Control of invasion by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition programs during metastasis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019 May 10;8(5):646.

- Briggs A. Osteomimicry in Breast Cancer: Microcalcifications in Breast Epithelial Cell Lines (Master's thesis, State University of New York at Buffalo).

- Loh CY, Chai JY, Tang TF, Wong WF, Sethi G, Shanmugam MK, Chong PP, Looi CY. The E-cadherin and N-cadherin switch in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: signaling, therapeutic implications, and challenges. Cells. 2019 Sep 20;8(10):1118.

- Abd ElMoneim HM, Zaghloul NM. Expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin and snail and their correlation with clinicopathological variants: an immunohistochemical study of 132 invasive ductal breast carcinomas in Egypt. Clinics. 2011 Oct 1;66(10):1765-71.

- Li B, Shi H, Wang F, Hong D, Lv W, Xie X, Cheng X. Expression of E-, P-and N-cadherin and its clinical significance in cervical squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions. PloS one. 2016 May 25;11(5):e0155910.

- Tomita K, van Bokhoven A, van Leenders GJ, Ruijter ET, Jansen CF, Bussemakers MJ, Schalken JA. Cadherin switching in human prostate cancer progression. Cancer research. 2000 Jul 1;60(13):3650-4.

- Dedhar S. Integrins and tumor invasion. Bioessays. 1990 Dec;12(12):583-90.

- Eble JA, Haier J. Integrins in cancer treatment. Current cancer drug targets. 2006 Mar 1;6(2):89-105.

- De Wever O, Mareel M. Role of tissue stroma in cancer cell invasion. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2003 Jul;200(4):429-47.

- Pepper MS. Role of the matrix metalloproteinase and plasminogen activator–plasmin systems in angiogenesis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2001 Jul;21(7):1104-17.

- Stickeler E. Prognostic and predictive markers for treatment decisions in early breast cancer. Breast Care. 2011 Jun 14;6(3):193-8.

- Nicolini A, Ferrari P, Duffy MJ. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in breast cancer: Past, present and future. InSeminars in cancer biology 2018 Oct 1 (Vol. 52, pp. 56-73). Academic Press.

- Bouchet C, Spyratos F, Martin PM, Hacene K, Gentile A, Oglobine J. Prognostic value of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and plasminogen activator inhibitors PAI-1 and PAI-2 in breast carcinomas. British journal of cancer. 1994 Feb;69(2):398-405.

- Scully OJ, Bay BH, Yip G, Yu Y. Breast cancer metastasis. Cancer genomics & proteomics. 2012 Sep 1;9(5):311-20.

- Joyce H. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance and invasion in a human lung carcinoma cell line (Doctoral dissertation, Dublin City University).

- SV AV. Estimation of Tetranectin Levels in Saliva of Patients with and Without Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Using Quantitative Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay–A Cross Sectional Study (Master's thesis, Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences (India)).

- Barash U, Cohen?Kaplan V, Dowek I, Sanderson RD, Ilan N, Vlodavsky I. Proteoglycans in health and disease: new concepts for heparanase function in tumor progression and metastasis. The FEBS journal. 2010 Oct;277(19):3890-903.

- Vlodavsky I, Beckhove P, Lerner I, Pisano C, Meirovitz A, Ilan N, Elkin M. Significance of heparanase in cancer and inflammation. Cancer microenvironment. 2012 Aug;5:115-32.

- Hammond E, Khurana A, Shridhar V, Dredge K. The role of heparanase and sulfatases in the modification of heparan sulfate proteoglycans within the tumor microenvironment and opportunities for novel cancer therapeutics. Frontiers in oncology. 2014 Jul 24;4:195.

- Parish CR, Freeman C, Hulett MD. Heparanase: a key enzyme involved in cell invasion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Cancer. 2001 Mar 21;1471(3):M99-108.

- Meirovitz A, Goldberg R, Binder A, Rubinstein AM, Hermano E, Elkin M. Heparanase in inflammation and inflammation?associated cancer. The FEBS journal. 2013 May;280(10):2307-19.

- Levy-Adam F, Ilan N, Vlodavsky I. Tumorigenic and adhesive properties of heparanase. InSeminars in cancer biology 2010 Jun 1 (Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 153-160). Academic Press.

- Rabelink TJ, Van Den Berg BM, Garsen M, Wang G, Elkin M, Van Der Vlag J. Heparanase: roles in cell survival, extracellular matrix remodelling and the development of kidney disease. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2017 Apr;13(4):201-12.

- Levy-Adam F, Abboud-Jarrous G, Guerrini M, Beccati D, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Identification and characterization of heparin/heparan sulfate binding domains of the endoglycosidase heparanase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005 May 27;280(21):20457-66.

- Vuoriluoto K. Anchor or Accelerate–A Study on Cancer Cell Adhesion and Motility.

- Wells A, Kassis J, Solava J, Turner T, Lauffenburger DA. Growth factor-induced cell motility in tumor invasion. Acta Oncologica. 2002 Jan 1;41(2):124-30.

- Sloan KE, Eustace BK, Stewart JK, Zehetmeier C, Torella C, Simeone M, Roy JE, Unger C, Louis DN, Ilag LL, Jay DG. CD155/PVR plays a key role in cell motility during tumor cell invasion and migration. BMC cancer. 2004 Dec;4:1-4.

- Wang W, Goswami S, Sahai E, Wyckoff JB, Segall JE, Condeelis JS. Tumor cells caught in the act of invading: their strategy for enhanced cell motility. Trends in cell biology. 2005 Mar 1;15(3):138-45.

- Bravo-Cordero JJ, Hodgson L, Condeelis J. Directed cell invasion and migration during metastasis. Current opinion in cell biology. 2012 Apr 1;24(2):277-83.

- DOHOON K, SUNHONG K, HYONGJONG K, SANG?OH YO, AN?SIK CH, KYOUNG SANG CH, JONGKYEONG C. Akt/PKB promotes cancer cell invasion via increased motility and metalloproteinase production. The FASEB Journal. 2001 Sep;15(11):1953-62.

- Paul CD, Mistriotis P, Konstantopoulos K. Cancer cell motility: lessons from migration in confined spaces. Nature reviews cancer. 2017 Feb;17(2):131-40.

- De la Fuente IM, López JI. Cell motility and cancer. Cancers. 2020 Aug 5;12(8):2177.

- Han T, Kang D, Ji D, Wang X, Zhan W, Fu M, Xin HB, Wang JB. How does cancer cell metabolism affect tumor migration and invasion?. Cell adhesion & migration. 2013 Sep 25;7(5):395-403.

- Fedotov S, Iomin A. Migration and proliferation dichotomy in tumor-cell invasion. Physical Review Letters. 2007 Mar 16;98(11):118101.

- Iida J, Meijne AM, Knutson JR, Furcht LT, McCarthy JB. Cell surface chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in tumor cell adhesion, motility and invasion. InSeminars in cancer biology 1996 Jun 1 (Vol. 7, No. 3, p. 155). Philadelphia, PA, USA: Saunders Scientific Publications, c1990-.

- Ma Y, Yu WD, Su B, Seshadri M, Luo W, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Regulation of motility, invasion, and metastatic potential of squamous cell carcinoma by 1?, 25?dihydroxycholecalciferol. Cancer. 2013 Feb 1;119(3):563-74.

- O'Connor K, Chen M. Dynamic functions of RhoA in tumor cell migration and invasion. Small GTPases. 2013 Jul 1;4(3):141-7.

- Trepat X, Chen Z, Jacobson K. Cell migration. Comprehensive Physiology. 2012 Oct;2(4):2369.

- Tsutsumi S, Scroggins B, Koga F, Lee MJ, Trepel J, Felts S, Carreras C, Neckers L. A small molecule cell-impermeant Hsp90 antagonist inhibits tumor cell motility and invasion. Oncogene. 2008 Apr;27(17):2478-87.

- Yamazaki D, Kurisu S, Takenawa T. Involvement of Rac and Rho signaling in cancer cell motility in 3D substrates. Oncogene. 2009 Apr;28(13):1570-83.

- Vial E, Sahai E, Marshall CJ. ERK-MAPK signaling coordinately regulates activity of Rac1 and RhoA for tumor cell motility. Cancer cell. 2003 Jul 1;4(1):67-79.

- Guan X, Guan X, Dong C, Jiao Z. Rho GTPases and related signaling complexes in cell migration and invasion. Experimental cell research. 2020 Mar 1;388(1):111824.

- Matsuoka T, Yashiro M. Rho/ROCK signaling in motility and metastasis of gastric cancer. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2014 Oct 10;20(38):13756.

- Zohrabian VM, Forzani B, Chau Z, Murali RA, Jhanwar-Uniyal M. Rho/ROCK and MAPK signaling pathways are involved in glioblastoma cell migration and proliferation. Anticancer research. 2009 Jan 1;29(1):119-23.

- Alexandrova AY, Chikina AS, Svitkina TM. Actin cytoskeleton in mesenchymal-to-amoeboid transition of cancer cells. International review of cell and molecular biology. 2020 Jan 1;356:197-256.

- Friedl P. Prespecification and plasticity: shifting mechanisms of cell migration. Current opinion in cell biology. 2004 Feb 1;16(1):14-23.

- Vaškovi?ová K, Szabadosová E, ?ermák V, Gandalovi?ová A, Kasalová L, Rösel D, Brábek J. PKC? promotes the mesenchymal to amoeboid transition and increases cancer cell invasiveness. BMC cancer. 2015 Dec;15:1-1.

- Reyes R. Amoeboid Transition Occurs in Mammilian Tumor Cells in Response to Changes in Spacial Confinement and Adhesion (Master's thesis, The University of Arizona).

- Te Boekhorst V, Friedl P. Plasticity of cancer cell invasion—Mechanisms and implications for therapy. Advances in cancer research. 2016 Jan 1;132:209-64.

- Limia CM, Sauzay C, Urra H, Hetz C, Chevet E, Avril T. Emerging roles of the endoplasmic reticulum associated unfolded protein response in cancer cell migration and invasion. Cancers. 2019 May 6;11(5):631.

- Friedl P, Wolf K. Plasticity of cell migration: a multiscale tuning model. Journal of Cell Biology. 2010 Jan 11;188(1):11-9.

- Jobe NP, Åsberg L, Andersson T. Reduced WNT5A signaling in melanoma cells favors an amoeboid mode of invasion. Molecular Oncology. 2021 Jul;15(7):1835-48.

- Geum DT, Kim BJ, Chang AE, Hall MS, Wu M. Epidermal growth factor promotes a mesenchymal over an amoeboid motility of MDA-MB-231 cells embedded within a 3D collagen matrix. The European Physical Journal Plus. 2016 Jan;131:1-0.

- Tognoli ML, Vlahov N, Steenbeek S, Grawenda AM, Eyres M, Cano-Rodriguez D, Scrace S, Kartsonaki C, von Kriegsheim A, Willms E, Wood MJ. RASSF1C oncogene elicits amoeboid invasion, cancer stemness and invasive EVs via a novel SRC/Rho axis. bioRxiv. 2021 Jan 6:2021-01.

- Tearle J. Uncovering the Mechanisms Underpinning Melanoma Invasiveness at Single Cell Resolution (Doctoral dissertation, UNSW Sydney).

- Omata S, Fukuda K, Sakai Y, Ohuchida K, Morita Y. Effect of extracellular matrix fiber cross-linkage on cancer cell motility and surrounding matrix deformation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2023 Sep 17;673:44-50.

- Guo S, Deng CX. Effect of stromal cells in tumor microenvironment on metastasis initiation. International journal of biological sciences. 2018;14(14):2083.

- Alphonso A, Alahari SK. Stromal cells and integrins: conforming to the needs of the tumor microenvironment. Neoplasia. 2009 Dec 1;11(12):1264-71.

- Kopfstein L, Christofori G. Metastasis: cell-autonomous mechanisms versus contributions by the tumor microenvironment. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences CMLS. 2006 Feb;63:449-68.

- Kamdje AH, Kamga PT, Simo RT, Vecchio L, Etet PF, Muller JM, Bassi G, Lukong E, Goel RK, Amvene JM, Krampera M. Mesenchymal stromal cells’ role in tumor microenvironment: involvement of signaling pathways. Cancer biology & medicine. 2017 May;14(2):129.

- Poggi A, Musso A, Dapino I, Zocchi MR. Mechanisms of tumor escape from immune system: role of mesenchymal stromal cells. Immunology letters. 2014 May 1;159(1-2):55-72.

- Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the'seed and soil'hypothesis revisited. Nature reviews cancer. 2003 Jun 1;3(6):453-8.

- Langley RR, Fidler IJ. The seed and soil hypothesis revisited—The role of tumor?stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. International journal of cancer. 2011 Jun 1;128(11):2527-35.

- Pienta KJ, Robertson BA, Coffey DS. The Cancer Diaspora: Metastasis beyond the Seed and Soil.

- De Groot AE, Roy S, Brown JS, Pienta KJ, Amend SR. Revisiting seed and soil: examining the primary tumor and cancer cell foraging in metastasis. Molecular Cancer Research. 2017 Apr 1;15(4):361-70.

- Ugurlu G. A novel tumor metastatic pathway driven by high VEGF-A production (Doctoral dissertation).

- Witz IP. Yin-yang activities and vicious cycles in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer research. 2008 Jan 1;68(1):9-13.

- Ribatti D, Mangialardi G, Vacca A. Stephen Paget and the ‘seed and soil’theory of metastatic dissemination. Clinical and experimental medicine. 2006 Dec;6:145-9.

- McGee SF. Understanding metastasis: current paradigms and therapeutic challenges in breast cancer progression.

- Maman S, Witz IP. A history of exploring cancer in context. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2018 Jun;18(6):359-76.

- Maman S, Witz IP. A history of exploring cancer in context. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2018 Jun;18(6):359-76.

- Buijs JT, van der Pluijm G. Osteotropic cancers: from primary tumor to bone. Cancer letters. 2009 Jan 18;273(2):177-93.

- Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. Cancer metastases: so close and so far. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015 Nov 1;107(11):djv236.

- Mallin MM, Pienta KJ, Amend SR. Cancer cell foraging to explain bone-specific metastatic progression. Bone. 2022 May 1;158:115788.

- Doglioni G, Parik S, Fendt SM. Interactions in the (pre) metastatic niche support metastasis formation. Frontiers in oncology. 2019 Apr 24;9:219.

- Ya G, Ren W, Qin R, He J, Zhao S. Role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the formation of pre-metastatic niche. Frontiers in Oncology. 2022 Sep 27;12:975261.

- Mortezaee K. Organ tropism in solid tumor metastasis: an updated review. Future Oncology. 2021 May;17(15):1943-61.

- Thibaudeau L, Quent VM, Holzapfel BM, Taubenberger AV, Straub M, Hutmacher DW. Mimicking breast cancer-induced bone metastasis in vivo: current transplantation models and advanced humanized strategies. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2014 Sep;33:721-35.

- Rucci N, Sanita P, Angelucci A. Roles of metalloproteases in metastatic niche. Current molecular medicine. 2011 Nov 1;11(8):609-22.

- Taverna S, Giusti I, D’Ascenzo S, Pizzorno L, Dolo V. Breast cancer derived extracellular vesicles in bone metastasis induction and their clinical implications as biomarkers. International journal of molecular sciences. 2020 May 18;21(10):3573.

- Smith HA, Kang Y. The metastasis-promoting roles of tumor-associated immune cells. Journal of molecular medicine. 2013 Apr;91:411-29.

- Graney PL, Tavakol DN, Chramiec A, Ronaldson-Bouchard K, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Engineered models of tumor metastasis with immune cell contributions. Iscience. 2021 Mar 19;24(3).

- Sulekha Suresh D, Guruvayoorappan C. Molecular principles of tissue invasion and metastasis. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2023 May 1;324(5):C971-91.

- García-Silva S, Peinado H. Mechanisms of Lymph Node Metastasis: An Extracellular Vesicle Perspective. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2024 Aug 2:151447.

- Roato I, Ferracini R. Cancer stem cells, bone and tumor microenvironment: key players in bone metastases. Cancers. 2018 Feb 20;10(2):56.

- Zoni E, van der Pluijm G. The role of microRNAs in bone metastasis. Journal of bone oncology. 2016 Sep 1;5(3):104-8.

- Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. InSeminars in oncology 2002 Dec 16 (Vol. 29, No. 6, pp. 15-18). WB Saunders.

- Baeriswyl V, Christofori G. The angiogenic switch in carcinogenesis. InSeminars in cancer biology 2009 Oct 1 (Vol. 19, No. 5, pp. 329-337). Academic Press.

- Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nature reviews cancer. 2003 Jun 1;3(6):401-10.

- Bikfalvi A. Significance of angiogenesis in tumour progression and metastasis. European Journal of Cancer. 1995 Jul 1;31(7-8):1101-4.

- Sugimachi K, Tanaka S, Terashi T, Taguchi KI, Rikimaru T, Sugimachi K. The mechanisms of angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: angiogenic switch during tumor progression. Surgery. 2002 Jan 1;131(1):S135-41.

- Gao D, Nolan DJ, Mellick AS, Bambino K, McDonnell K, Mittal V. Endothelial progenitor cells control the angiogenic switch in mouse lung metastasis. Science. 2008 Jan 11;319(5860):195-8.

- Adams J, Carder PJ, Downey S, Forbes MA, MacLennan K, Allgar V, Kaufman S, Hallam S, Bicknell R, Walker JJ, Cairnduff F. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in breast cancer: comparison of plasma, serum, and tissue VEGF and microvessel density and effects of tamoxifen. Cancer research. 2000 Jun 1;60(11):2898-905.

- Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992 Oct 29;359(6398):843-5.

- Hata Y, Nakagawa K, Sueishi K, Ishibashi T, Inomata H, Ueno H. Hypoxia-induced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by retinal glial cells promotes in vitro angiogenesis. Virchows Archiv. 1995 Jun;426:479-86.

- Rofstad EK, Danielsen T. Hypoxia-induced angiogenesis and vascular endothelial growth factor secretion in human melanoma. British journal of cancer. 1998 Mar;77(6):897-902.

- Anampa J, Makower D, Sparano JA. Progress in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: an overview. BMC medicine. 2015 Dec;13:1-3.

- Hussain SA, Palmer DH, Stevens A, Spooner D, Poole CJ, Rea DW. Role of chemotherapy in breast cancer. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2005 Dec 1;5(6):1095-110.

- Higgins MJ, Baselga J. Targeted therapies for breast cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011 Oct 3;121(10):3797-803.

- Drãgãnescu M, Carmocan C. Hormone therapy in breast cancer. Chirurgia. 2017 Jul 1;112(4):413-7.

- Santen RJ. Menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2014 Jul 1;142:52-61.

- Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL. Changing concepts: menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012 Apr 4;104(7):517-27.

- Bayraktar S. Immunotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Disease: Management and Therapies, Volume 2. 2019:541-52.

- Debien V, De Caluwé A, Wang X, Piccart-Gebhart M, Tuohy VK, Romano E, Buisseret L. Immunotherapy in breast cancer: an overview of current strategies and perspectives. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2023 Feb 13;9(1):7.

- Emens LA. Breast cancer immunotherapy: facts and hopes. Clinical cancer research. 2018 Feb 1;24(3):511-20.

- Nielsen DL, Andersson M, Andersen JL, Kamby C. Antiangiogenic therapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research. 2010 Oct;12:1-6.

- Kerbel RS. Reappraising antiangiogenic therapy for breast cancer. The Breast. 2011 Oct 1;20:S56-60.

- Miller KD, Dul CL. Breast cancer: the role of angiogenesis and antiangiogenic therapy. Hematology/Oncology Clinics. 2004 Oct 1;18(5):1071-86.

- Harnoss JM, Le Thomas A, Reichelt M, Guttman O, Wu TD, Marsters SA, Shemorry A, Lawrence DA, Kan D, Segal E, Merchant M. IRE1? disruption in triple-negative breast cancer cooperates with antiangiogenic therapy by reversing ER stress adaptation and remodeling the tumor microenvironment. Cancer research. 2020 Jun 1;80(11):2368-79.

Arnab Roy*

Arnab Roy*

K. Rajeswar Dutt

K. Rajeswar Dutt

Ankita Singh

Ankita Singh

Mahesh Kumar Yadav

Mahesh Kumar Yadav

Anupama Kumari

Anupama Kumari

Anjali Raj

Anjali Raj

Umaira Sahid

Umaira Sahid

Rashmi Kumari

Rashmi Kumari

Archana Rani

Archana Rani

Maheshwar Kumar

Maheshwar Kumar

Nahida Khatun

Nahida Khatun

Tahmina Khatoon

Tahmina Khatoon

Nisha Rani

Nisha Rani

Shweta Kumari

Shweta Kumari

Divyanshi

Divyanshi

10.5281/zenodo.13356608

10.5281/zenodo.13356608